Deconversion and Abuse

Several years ago when I published my initial model of deconversion, one of the responses I received was that it did not include the people who left for reasons of abuse by the church. In the initial 32 case studies I considered when forming my model, I had not seen anything which resembled a pattern of abuse or mistreatment. Granted, several of the deconverts complained that the various teachings and doctrines caused emotional distress, but this was mostly in retrospect, and certainly not what I considered direct and malicious abuse from the church.

However, in the intervening years, the subject of abuse, religious trauma, and “church hurt” have begun dominating the discussion in much the same way as Christian anti-intellectualism had in the preceding decades.

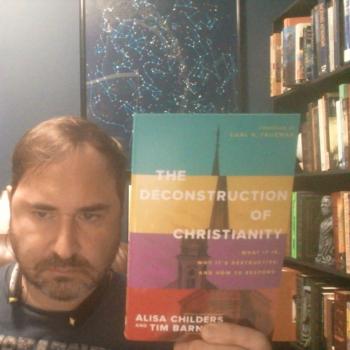

In previous articles I have examined the somewhat scant research around the topic of religious abuse, but I recently decided to go back to the start and read the book which famously coined the term, a book titled The Subtle Power of Spiritual Abuse (Johnson & Van Vonderen, 1992).

A Book Encouraging Christians Who Have Been Hurt

Picking the book up, I expected it to be similar to the recent literature, criticizing Christianity and painting it as an inherently abusive institution. However, this book was written about a decade prior to the rise of New Atheism, and a good 30 years prior to the Deconstruction Movement. It was written in a time when the United States was still solidly majority Christian, and it was possible to criticize particular ways of practicing Christianity without portraying the entire system as being rotten and malevolent. Consequently, this book – written by two Christian pastors – pointed out ways in which certain religious environments misused the spiritual authority lent to them by the trust of religious individuals in such a way as to cause psychological harm to those individuals.

The authors of the book were both counseling pastors, and as such, they drew the information for the book largely from the many cases they had seen in counseling rather than any kind of systematic or empirical research. The pastors then proceeded to make Biblical arguments for why these sorts of misuses of power were wrong, and then use the Bible to offer help and guidance for those people who might have fallen victim to these kinds of abuses.

The abuses detailed by these authors included a variety of things. The more tame abuses included using the Bible to excuse one’s own behavior. Less tame would be to use Bible verses to demand behaviors from other Christians. The authors recounted church leaders who placed themselves in the position of being mouthpieces for God, and therefore unquestionable in their authority. A stomach-churningly high number of these accounts involved people using spiritual authority as a pretext to ultimately sexually abuse individuals – contradicting the title by presenting some very un-subtle instances of abuse. These people were frequently permitted to escape the consequences of their crimes because of the protection offered by the church – the most serious repercussions often being a simple dismissal from the church without the appropriate legal consequences. Upon exiting the church, it was sometimes the case that church members would then lay blame on the abuse victim for the firing of the pastor.

A more subtle form of spiritual abuse detailed by the writers was the tendency of some church environments to make the members overly spiritually dependent on church authorities, such that every small decision or occurrence in their lives would need to be reported to the pastor in order to receive the necessary spiritual input to handle the situation. Upon leaving the church, this frequently left the individual paralyzed when needing to make a decision after having become entirely dependent on the church to make decisions for him or her.

What the authors noted was that people who had undergone such abuses could frequently be identified by the anxiety and avoidance they developed around ministers and within church environments. The solutions the authors offered were varied, but always boiled down to some form of allowing the victim to take back agency over his or her life, identify when they were in an environment that was manipulating them and escape that environment, and separate God from the church rather than conflating the two as identical.

Relating the Book to Research

It is not within the scope of this article to list all of the forms of abuse dealt with by this book, nor all of the responses given by the authors. However, it is interesting to take a look at the work in relationship to my research.

The first thing which was conspicuously absent within this book was any mention of deconversion. Perhaps a vague allusion to it was made in an offhanded way at one point in the book, but surprisingly the authors appeared to suggest that people became entrapped in such environments, and that it was their purpose to help people identify when they were being abused and transition to a healthier church environment. This lay in stark contrast to the similar work of Marlene Winell written only a few years later which focused on how to help victims to escape Christianity entirely, and the current Deconstruction trend which has the tendency to identify specific ways in which religious authority is used to dominate people and then generalize this to Christianity as a system. These authors were presenting a case against such arguments before they were even advanced. These authors were arguing that a church could be a healthy, nurturing environment which allowed its attendees agency while remaining faithful to scriptural teachings.

And unlike more recent authors such as Brian McLaren, these authors did not adopt a “the only law is love” approach, wherein the only way to give people true religious freedom would be to adopt a very vague allegiance to the principle of “love” without defining any way in which such love would be implemented.

Written, as it was, in the early 1990s, this book failed to address the pressing issues which are at the forefront of the public eye in the 21st century, and are the focus of much of the academic work being published on religious abuse. Those being issues around politics and sexuality. It is difficult from what is written in the book to determine how these authors would have addressed these issues.

Regarding the subject of deconversion, it is likely that this was not a subject addressed within this work due to the fact that atheism had not yet become a viable social institution. When one was forced to exit one’s religious environment due to abuse, one’s options were limited. Frequently one went from one religious environment to another until one found an environment which was compatible with one’s emotional needs. With the world far more secularized than it once was, exiting the church entirely is now easier than it was at the time.

What this book did provide was confirmation of what the research already suggests: that deconversion is most frequently found in highly authoritarian churches, churches which place a significant barrier between members and the world at large, and churches in which members hold each other to prohibitive standards taking agency away from any member who might choose to dissent from the common ethos of the religious body.

Is this book still worth a look in 21st century America? It seems like this would be a valuable resource for people within the Deconstruction Movement who have not yet committed to exiting their religious faith. Old as it is, the kinds of abuses the book addresses are as current as they ever were, and encompass a great deal of the objections modern dissidents have.

The book isn’t particularly helpful in terms of modern research, and would not be helpful to someone who does not buy in to the idea that the Bible is authoritative or has anything of value to offer.