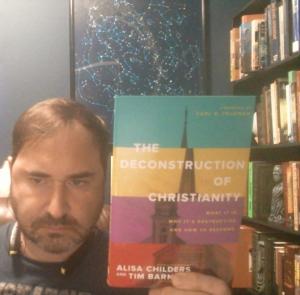

Like so many of the books written in recent years on the topic of the exodus from Christianity, The Deconstruction of Christianity (2023) was written by Christians with the purpose of explaining this exodus, comforting Christians who have lost friends and family to the exodus, and defending the truth of Christianity to those who were in the process of “Deconstructing.”

However, this book does add a unique element to the discussion which has been absent in previous literature I have read on the subject. First, it deals with the dimensions of the “Deconstruction Movement” – a social force which has more or less supplanted the “New Atheist Movement” in the last ten years as the most culturally visible driver of people leaving the church. The Deconstruction Movement has, to some degree, absorbed the New Atheist Movement and replaced it. But in the popular and academic literature it has not been particularly well-defined or studied. While Childers’ and Barnett’s book is not academic in nature, it does an admirable job defining and exploring the dimensions of this movement.

The second thing this book contributes to the literature is an in-depth exploration of the philosophical underpinnings of “deconstruction,” and how this idea which was created and advocated for by French philosopher Jacques Derrida in the 1970s can be linked to modern religious deconstruction, even though the two do not explicitly claim a relationship.

Like most Christian books on the subject, this book contains a number of anecdotal accounts of individuals who have left the church and their reasons for doing so. Though anecdotal accounts are relatively useless in isolation, enough of them put together begin to obtain a statistical quality which my extensive reading on this subject has permitted me to survey.

“Deconstruction”

In my previous writing on this subject, I have expressed my dislike of the term “Deconstruction.” I have three general reasons for not using this term in my work. The first is that it has become popular slang, and like most slang, it shifts and adopts new meanings over brief intervals of time, such that any two people using the word may mean two different things. Since academic work strains for accuracy, pop culture slang has no place in research. Childers and Barnett capture this in their book as they describe the evolution of the word “deconstruction” from its philosophical roots, to its use as a term for exiting the Christian faith, to its reappropriation in church circles to describe a way in which individuals critically examine their religious beliefs to find new ways to exercise Christianity.

The second reason I avoid the use of this word is that in the research, the preferred term for leaving religion still remains “deconversion.” As I am primarily functioning as a researcher, I prefer to use the lexicon of my craft.

The third reason is that “Deconstruction” is philosophically loaded, given its original use in Existential philosophy, and to use it as a psychological term would be to confuse two separate areas of academic inquiry.

However, given that deconstruction isn’t just a verb to describe a mental process, but also a noun to describe a cultural Movement, it is appropriate for the book Childers and Barnett wrote.

The Deconstruction Movement

Childers and Barnett speak of this movement for what it is: a matter of questioning the church as an institution, the sorts of values and ideologies pushed by the church, and the kinds of behavior one sees within church circles which drive people away. The most egregious of these behaviors being people with positions of authority – pastors, for instance – using that authority as a method by which they can enact abuses on church members. The less egregious but still damning behavior in the church being the hypocrisy of its members.

Individuals who have deconstructed or are undergoing deconstruction are most specifically concerned with the emotional damage which has been done to them by the church, and the ways in which they feel uncomfortable or distinctly rejected by the church community. The authors do, however, speak to the political tensions which have mounted within the country at large contributing to the rejection of Christianity by young people.

A Shift in Meaning

The authors note that, as the term Deconstruction gradually seeped into the cultural lexicon, churches and religious leaders have made an attempt at reappropriating the word in a kind of trendy Christian way. The term has been broadened to mean the asking of questions about beliefs, and changing one’s beliefs to be more in line with one’s personal feelings. While this may involve leaving the church, it could also involve practicing one’s faith in a more authentic way. The authors do not seem particularly warm to this approach, suggesting that – while they are open to investigation into one’s beliefs and to asking authentic questions – they believe that this generalization of the term is liable to lead to confusion and a sort of “motte and bailey” tactic wherein one can claim to be doing one thing when they are actually engaged in the other. Christians could invade Deconstruction communities claiming to be Deconstructing with the ambiguity as to what that actually means, just as Deconstructionists could integrate within Christian circles to encourage members to question their faith.

The authors further examine the philosophical origins of the term “Deconstruction,” which originated with a French intellectual who suggested that the use of language was entirely contextual, and that to determine the meaning of any given writing, one would have to examine the entire context in which that writing was taking. In so doing, the philosopher was tearing language apart and stripping it of the power it had to communicate. The Deconstruction Community likely adopted the term because it was the opposite of “Construction,” and had the obvious meaning of systematically questioning and discarding aspects of their belief systems until nothing remained.

The Rest

The remainder of the book involved offering comforting words to friends and family who had lost someone to deconstruction, offering defenses to the common objections given by deconstructionists, reaching out in sympathy to any readers who were deconstructing, and offered advice to the church. The book is very readable, and well-suited for the audience it hopes to reach. For people who have left the church, or people who are entirely unchurched, it is possible that the book would be somewhat frustrating, given that it likely would not speak directly to the reader’s experience. The authors try to be as gentle, sympathetic, and charitable as they are able, so this book does not read like an average apologetics book aggressively championing the faith and disparaging disbelievers.

For the purposes of research, it does an excellent job of capturing the cultural moment we currently occupy. But given how rapidly the trend has been changing over the years, the book likely has a shelf-life of five years or less before culture and the church have moved on to the next thing.