A Definition

As we continue to blur the lines of right and wrong, it is important to return to the basics and explore the ancient, historical origins of concepts of morality, virtue and even personhood. In this post, I want to explore how we have moved from an ancient, objective perspective of virtue to a subjective, often agenda-based ideology of virtue.

Plato and Aristotle are Western pioneers of this school of thought and in the East, we find Confucius and Mencius. These thinkers would be the prominent thinkers until the Enlightenment. (See https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/ethics-virtue/ ).

Historically, from the classic Greek perspective, virtue was defined as moral excellence and righteousness. In its purest sense, collectively in Greek society, everyone would have agreed what an honest person looked like and acted. Here, consistency was key.

Jewish Ethics – The Religion of Jesus

As a Christian, I often want to consider the religion of Jesus to understand what and how to believe. To understand what Jesus believed and why it was important to him helps better inform me on the posture I need to take as a follower of a religion that became a religion about him. A concept that may have been on Jesus’ radar was the concept of Mussar. This idea is found 51 times in the bible and wrestles with the question, “why is hard to be good?”

“Why is it hard to be good?”

In Judaism, we find the concept of Mussar. Mussar is “a Jewish spiritual practice that gives concrete instructions on how to live a meaningful and ethical life, arose as a response to this concern. Here, the emphasis is on the idea that just learning about kindness does not make you kind. We need to cultivate inner values. (see )

Mussar is virtue-based ethics — based on the idea that by cultivating inner virtues, we improve ourselves. This contrasts with most Jewish ethical teachings, which are rule-based” (Marcus). While I am a bit fuzzy on how this directly applies to Jesus, his “you have heard it said” statements seem to fall in line with this way of thinking.

Much of what is known of modern thoughts around Mussar come from the Middle Ages up to today.

How Christian Ethics are not Necessarily Christian

There is a lot of talk in Christian circles about what the Bible says. Too often, we are worried about right morality than a deeper relationship with God and those who went before us. The Bible does not say anything. It does however inform us about a particular group of people at a particular point in time.

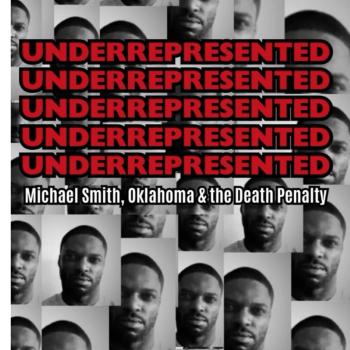

There is also a particular disdain with the current voices of Christian Nationalism for pluralism. I have found myself asked to leave Christian circles for suggesting the God of Islam is the same God of Christianity. Pluralism is the peaceful coexistence of multiple religions in a community. It recognizes and tolerates the diversity of multiple religions in a society or a country. With this recognition comes the promotion of freedom of religion and “secularism as neutrality (of the state or non-sectarian institution) on issues of religion as opposed to opposition of religion in the public forum or public square that is open to public expression and promoting friendly separation of religion and state as opposed to hostile separation or antitheism espoused by other forms of secularism” (Wikipedia).

In the previous sections, we have seen how different culture have influenced Christian thinking. Eventually, Judaism influences would wane completely as the movement started by Jesus became a religion about Jesus.

The Core Seven

In Christianity, we often identify seven core virtues. I aim here to point to both the Christian importance of these virtues and focus specifically on the cultural influences that shaped these virtues.

Four of the virtues are Greek in influence. Also known as the Cardinal virtues, these virtues can be found in origin in the writings of Plato, Aristotle and Socrates. They are prudence, temperance, fortitude, and justice. Stoicism (Stoic virtues ) the virtues of wisdom, courage, temperance, and justice. For me, wisdom is what informs action. Wisdom is perhaps the greatest of all the virtues as it signifies maturity. I don’t mean maturity as in the idea that you are all grown up and have your stuff together. I mean maturity across several planes of existence, mental maturity (which psychology has demonstrated happens at a certain point of time) and spiritual maturity (which happens when one develops and maintains a deep relationship with the inner self and the unitive experience).

Three of the virtues are more theological in nature, these are faith, hope and love. Love has deep roots in Greek thought with up to 9 different types of love. For Christians, love is the standard by which all else is to be judged and to which, in the case of a conflict of duties, the prior claim must be yielded. It is often the most misunderstood, culturally appropriated and wrongly interpreted virtue. That line from “Princess Bride” comes to mind here, “you keep using that word, I don’t think it means what you think it means.”

Hope is a spiritual practice as much as it is a virtue (see my previous post https://www.patheos.com/blogs/loveopensdoors/2023/11/advent-spiritual-practice-hope/ ) And faith from my perspective is a philosophical orientation more than a virtue. Faith is culturally normative and generationally/historically guided. In the Wesleyan tradition, we reflect more on tradition. Tradition at least feels more usable because it has an objective nature to it whereas faith is always subjective.

Tying it all Together

Living a virtuous life is a contemplative practice. It is one that is rooted in many traditions across the world. To be done properly, one needs to engage in deep ecumenism and pluralism to fully engage with the teachings offered by different traditions. True wisdom is gained when one sees not only the complexities of each tradition, but also the similarities with each tradition. In psychology, we call this confirmation bias. This bias strengthens our understanding and firms up our beliefs.

Living a virtuous life is like planting seeds in a garden—each action and choice rooted in virtue fosters growth, beauty, and resilience both within ourselves and in the world around us. Living a virtuous life is an ongoing journey, one where each step brings us closer to our true selves and to the Divine. By embracing virtues, we not only enhance our individual lives but also contribute to the collective well-being of all. Through this practice, we help to uplift and heal our communities, making our shared world a more compassionate and harmonious place.

Reference:

Marcus, G. (n.d.). What Is Mussar? My Jewish Learning. Retrieved July 8, 2024, from https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/the-musar-movement/

Wikipedia (n.d.). Religious pluralism. Retrieved July 10, 2024, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Religious_pluralism