LONDON MISSIONARY SOCIETY

Evidence would suggest that “Kali Prasanna Chatterji” was the Theosophist, Kali Prasanna Mukherji (also a Kulin Brahmin.) First, we have a letter which Verochka wrote to her family on September 23, 1889, stating: “Isn’t it funny, mom, that the English missionaries chose me—a Russian, and the niece of the hated H.P. B.—to be a chairwoman at their school celebration?” The letter-head of the note bears the inscription of the London Missionary Society.[1] When considering that Kali Prasanna Mukherji was one of three native pastors for the London Missionary Society in Berhampore, there appears to be a connection.[2]

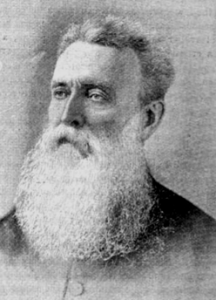

Rev. Samuel John Hill.[3]

The Missionary Society, as it was originally called, was founded in 1795 as the result of a conference between several evangelical representatives of the Church of England, Presbyterians, and Congregationalists. As time went on, denominational missionary societies were established, and, by degrees, the maintenance of the Society was left to the Congregationalists, though the undenominational constitution remained unchanged. The Berhampore branch of the London Missionary Society was founded in 1824 by Reverend Micaiah Hill, when the town was still a great military station. Hill and his wife opened seven schools for Hindus, two for Muslims, and one for girls, as “the ignorance and superstition of the lower classes [were] dense beyond description.”[4] In 1827 six boys’ schools remained, with 280 students, and a second girl’s school was opened with forty students. Three native chapels were then opened with three native preaching stations. In 1829 a large chapel was completed. To raise capital for a church, Hill kept silkworms and planted mulberry tended by the orphans. In 1853, Hill’s son, Reverend Samuel John Hill (born in Berhampore in 1825) assumed the responsibilities of the mission.

Nothing noteworthy occurred until 1880, when a mission-boat was built that enabled missionaries to travel over greater part of the district, and “preaching, teaching, the distribution of tracts, and the sale of Scriptures, were carried out zealously.”[5] Perhaps Kali Prasanna learned some useful skills regarding the production and distribution of religious tracts through his connection with the London Missionary Society. A letter from Kali Prasanna to Olcott at this time indicates that he was interested in establishing a “Bengal Theosophical Publishing Company,” like the one Tukaram Tatya had established in Bombay, and was petitioning “influential Bengali F.T.S.” for support in this effort.[6] (In the 1890s Kali Prasanna would collaborate with Baradakanta Majumdar on the Bengali Theosophical journal Kalpa.)[7]

In other religious news, religious controversy visited Murshidabad at this time, when a certain Jain family traveled to Europe. This was said to be the first instance of an Oswal Jain of the Swatanbaru sect “taking a pleasure cruise to England and Paris.” Meetings were held by various Jain communities to determine whether they had broken caste.[8] Nevertheless, the Jain Samaj at Baluchar had shown great sympathy to the Theosophical Society the previous year (1888.) Raj Danpat Sing Bahadur, of Baluchar, donated a complete set of works on Jain Religion to the library of the Adhi Bhoutic Bhratri T.S.[9]

On October 1, 1889, the Johnstons moved into new accommodations. In a letter to her family on October 7, Verochka writes:

It has been a week since we moved into our new accommodations, it consists of one-tenth of a huge cantonment that served as barracks for soldiers 20 years ago. Now these barracks are converted into public places, and the one in which we live is completely empty. We are on the top floor; the air is always fresh, and awful fumes do not reach us after rains. The servants live downstairs in separate quarters. The problem is, the government is going to move the post office [in the room] down stairs, and put up a postmaster’s wife in here…Then they’ll send us away, but at least we’ll live in some peace until then. Generally speaking, the Babus are lucky—they have all the best houses. The Europeans are the ones rotting from dampness, yet they assign all the dry barracks to the various Banerji’s and Mukerji’s for their silk-worm experiments. [10]

In a letter to her mother that October, Vera states: “I am writing shorter and shorter because India has drained me such, that I cannot write about it, and there is nothing to write about myself—everything is so monotonous. Besides, such a longing for you takes me, which is positively overwhelming.[11] We get a sense of her discomfort from another letter Vera wrote to her mother on October 20, 1889:

I am so annoyed with your “London Indians,” article.[12] You write about a young Brahmin of the Advaita sect and immediately call him a Buddhist. With few exceptions, like Baroness Kroummesse, there are no Buddhists in India. The only people of Hindu origin professing to Buddhists are the Sinhalese, but they have been exiled from India for many hundreds of years, and now live in Ceylon. More importantly, I am annoyed that you repeat Aunt Lelya’s exaggerations that “there are no natives in the crown service.” There are many postal chiefs, assistants to the chief of police, tellers, not to mention the clerks—they are all Bengalis. It is true that non-Christians are not permitted in military service, but this is because native officers murdered women and children in Kanpur 58 years ago. India is still full of the sons and brothers of these unfortunate people, so it should be clear why British officers do not wish to serve alongside the sons of these fanatics. I am genuinely surprised by Aunt Lelya. She has a prejudice against the British, but why she feel the need to sing the praises of the natives, I simply do not understand. In most cases they are fat, belching, fools, who consider themselves entitled to offend any poor man. I assure you, I am completely impartial, and I am not exaggerating—I even have friends among the Babus—but they lack motivation and drive, and a decent person among them is a rarity.[13]

← Table Of Contents →

SOURCES:

[1] Johnston, V. V. “Letters of Vera Johnston,” September 23/11, 1889, entry. The letterhead is mentioned in A. D. Tyurikova’s annotations for the letters of Vera Johnston found on the website of the Bakhmut Roerich Society.

[2] Walsh, J. H. Tull. A History of Murshidabad District (Bengal): With Biographies of Some of Its Noted Families. Jarrold & Sons. London, England. (1902): 70.

[3] W.J. “Rev. S.J. Hill, Of Berhampore.” The Chronicle Of The London Missionary Society. (March 1891): 81-86.

[4] Phillips, W.B. “The Leaven At Work.” The Chronicle Of The London Missionary Society. (October, 1890): 306-308.

[5] Gogerly, George. The Pioneers. John Snow & Co. London, England. (1871): 180-200; W.J. “Rev. S.J. Hill, Of Berhampore.” The Chronicle Of The London Missionary Society. (March 1891): 81-86; Walsh, J. H. Tull. A History Of Murshidabad District (Bengal): With Biographies Of Some Of Its Noted Families. Jarrold & Sons. London, England. (1902): 70.

[6] Kaliprasanna Mukherji writes: “I am trying to form a Bengal Theosophical Publishing Company for translating and publishing (1) Theosophical, (2) Rare Sanskrit, works in Bengali (the latter with original commentaries,) (3) Publishing cheap pamphlets on Theosophy in easy Bengali, and for (4) Editing cheap magazines on Theosophy and other kindred subjects, in Bengali. I hope some influential Bengali F.T.S. may be induced to take up the scheme. We have got many new members in our Branch, while your old familiar workers are still working hard for the cause. They have not allowed your favorite Branch to be inactive, and as long as even a single one of them remain, you would ever find a hearty home-like welcome in Berhampur and fervent expressions of unwavering loyalty to you, one of the Founders of a movement on which depends the only hope for regenerating poor fallen India.” Mukherji, K. P. “The Work In Berhampur.” Supplement To The Theosophist, Vol. XI (April 1890): cxxiii.

[7] Strube, Julian. Global Tantra. Oxford University Press. Oxford, England. (2022): 57-62.

[8] Rai Budsingh Bahadur Doodharia, (a wealthy zamindar banker,) and the members of his family, together with his son, Babu Indar Chand, and nephew, M. Nahatta, went to Europe. When they returned to India, they and joined their families. It was suspected by the Jain community that the family “anglicized themselves by going to England and dining in hotels,” and should not be allowed to give a certain feast which they proposed to give their Jain brethren. Meetings of other sections of the Jain community were called to consider the matter on October 20, 1890, in Calcutta. [“Deadly Sin Of Foreign Travel.” The Englishman’s Overland Mail. (London, England) October 22, 1889.] One orthodox member of the Jain community wrote to the newspapers: “I need not dwell here much upon the metaphysical qualities of a vegetarian life, but it will suffice to say that the countries and races are different in which it becomes impossible for a man to live without them. But are there not [teetotalers] and vegetarians even in those countries and among those classes of people?” [Chand, Gulal. “A Curious Letter On Jain Orthodoxy.” The Englishman’s Overland Mail. (London, England) October 22, 1889.]

[9] “Branches Of The Theosophical Society—Indian.“ General Report Of The Thirteenth Convention Of The Theosophical Society. (1889): 68-77.

[10] Vera writes: “It has been a week since we moved into our new accommodations, it consists of one-tenth of a huge cantonment that served as barracks for soldiers 20 years ago. Now these barracks are converted into public places, and the one in which we live is completely empty. We are on the top floor; the air is always fresh, and awful fumes do not reach us after rains. The servants live downstairs in separate quarters. The problem is the government is going to move the post office [in the room] downstairs and install the postmaster’s wife in here…Then they’ll send us away, but at least we’ll live in some peace until then. Generally speaking, the Babus are lucky—they have all the best houses. The Europeans are the ones rotting from dampness, yet they assign all the dry barracks to the various Banerjis and Mukerjis for their silk-worm experiments…”[Johnston, V. V. “Letters of Vera Johnston,” [g.] October 7, [j.] September 25, 1889, Berhampore, India, entry.]

[11] Johnston, V. V. “Letters of Vera Johnston,” October 20, 1889 [g.] , Berhampore , India, entry.]

[12] Zhelihovskaya, Vera Petrovna. “Two Evenings With London Indians Pt. I. .” News And Stock Exchange. No. 231. (August 23, 1889); Zhelihovskaya, Vera Petrovna. “Two Evenings With London Indians Pt. II.” News And Stock Exchange. No. 237. (August 29, 1889); Zhelihovskaya, Vera Petrovna. “Two Evenings With London Indians Pt. III.” News And Stock Exchange. No. 247. (September 3, 1889.)

[13] Johnston, V. V. “Letters of Vera Johnston,” October 7, 1889 [g.] , Berhampore , India, entry.]