It feels auspicious to return to Hinduism since we are near Diwali, the annual Hindu festival of lights. In Sanskrit, Diwali literally means “a row or series of lights” and has the connotation of lights which illuminate knowledge. If you google “Diwali,” you will see some spectacular images that merely touch the surface of the truly dazzling wonder that is Diwali. This holiday is truly a symphony for the senses.

Religion is about so much more than interpreting ancient texts. It’s about myths — the stories of meaning-making the tales we pass down to our children. Religion is symbolic rituals that we perform with our bodies. It’s traditional sights and sounds and special holiday meals and smells, all woven throughout our senses, memories and unconscious knowings.

Along these same lines, I found a recent social media post quite poignant. It was written by Neal Katyal, a law professor at Georgetown University, who has argued more U.S. Supreme Court cases than any other minority lawyer in U.S. history. Katyal shares, “When I was growing up, I hid Diwali from my classmates. No one knew what it was. Now it is being celebrated at [the home of the Vice President of the United States], with our first South Asian+African-American VP. Beyond my wildest dreams….”

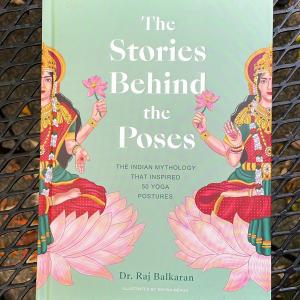

In the lead up to Diwali this year, I’ve been reading a book titled The Stories Behind the Poses: The Indian Mythology that Inspired 50 Yoga Postures, by Raj Balkarana. Part of what I appreciate most about Dr. Balkarana is that he is a scholar-practitioner who is both a renowned academic of Hindu mythology and a yogi who apprenticed himself to an Indian master for over a decade (224).

In the lead up to Diwali this year, I’ve been reading a book titled The Stories Behind the Poses: The Indian Mythology that Inspired 50 Yoga Postures, by Raj Balkarana. Part of what I appreciate most about Dr. Balkarana is that he is a scholar-practitioner who is both a renowned academic of Hindu mythology and a yogi who apprenticed himself to an Indian master for over a decade (224).

By no means is Dr. Balkarana presenting (or attempting to present) the one true version of what yoga poses mean. The Hindu Tradition is far too diverse and pluralistic for that. However, he is presenting one fairly mainstream set of interpretations.

Personally, yoga has been one of my spiritual practices for more than two decades. My interest in it started when I was in seminary. I was attending divinity school in Fort Worth, Texas, and one of my friends would travel regularly to Austin, where she was training to be a teacher in the Ashtanga Yoga tradition.

The next time I was in Austin, I went to her training with her. This first yoga class was in a heated room with some impressively advanced practitioners. I was in decent shape, and could keep up with them through most of the sequences. But toward the end, I just sat down and watched.

After more than two decades of yoga practice I still can’t do any truly hardcore poses, and to be honest I no longer aspire to. when I was in my mid-twenties, though, I did harbor ambitions of reaching advanced stages of yoga practice, but I’ve come to realize that I get a huge amount of benefit from a basic set of yoga poses, and that there is a significant risk of injury from some of the advanced practices, especially some of the extreme twists and bends. For more information along these lines, I recommend a great book that came out about a decade ago titled The Science of Yoga: The Risks and the Rewards by William Broad.

If you are yoga-curious, but have never tried it, my favorite yoga mantra is that, “Saying you’re too stiff to go do yoga is like saying you’re too cold to get out of the freezer.”

I also like to underscore that if you don’t have time for a full yoga practice, a significant amount of benefit can come from asking yourself: what one or two poses does my body need right now? Doing just one, two, or three poses for no more than one to five minutes can be surprisingly transformative.

If I’m really busy and have to pick just one yoga pose, it’s almost always Pigeon Pose, which helps counterbalance muscles that tighten from running. Your mileage may vary, and it’s important to experiment with what works for you.

In the spirit of Dr. Balkarana being a scholar-practioner, I will say just a few words about yoga from an academic perspective before we dive into a few of the stories and myths behind some of the yoga poses. If you are curious about all fifty of Dr. Balkarana’s selected poses, check out his book.

As Wendy Doniger, a religion professor at the University of Chicago, has traced, yoga as we know it today emerged from a fairly recent blending of cultures that resulted in part from the British colonization of India. Although some of the philosophic principles of yoga go back millennia:

Contemporary postural yoga was invented in India in the nineteenth century…. [And the international yoga that has now spread around the world is] compounded of the unlikely mix of British body-building and physical culture, American transcendentalism and Christian science, naturopathy, Swedish gymnastics and the YMCA, grated onto a rehabilitated form of postural yoga.” (On Hinduism, 120)

The truth behind the history of religious beliefs and practices is almost always complex, messy, and ever-evolving.

And although yoga can be beneficial both physically and spiritually without exploring the Hindu stories and myths behind the poses, a knowledge of the Hindu tradition can add profound spiritual depth to yoga. And as we prepare to hear some of the stories and myths behind the yoga poses, consider these opening reflections from Dr. Balkarana:

Storytelling is no ordinary thing…. While science is the arbiter of the empirical world…myths are tools for making meaning, most importantly about what it means to be human. Myths mirror the complexities of life. They are maps for the human journey and, as dramatizations of the inner life, they broach life’s big questions and life’s mysteries…. This book [of myths and stories] is for seekers and lovers of stories. It is also for those who wish to deepen their yoga practice. (6-7)

May we be open to the wisdom of these ancient stories as well as to the somatic wisdom of our bodies.

So now, without further ado, let’s get into a few poses and use them to exemplify how they are enriched by the myths and stories behind each of them. We’ll start with a relatively straightforward pose: Mountain Pose or Tadasana. Remember that adaptations are always available for bodies with limited mobility. For instance, a chair yoga modification might look like sitting more upright in your seat, whatever that means for your particular body.

When trying out the simple Mountain Pose, perhaps some of you will be thinking, why bother with this one? Is this pose really “doing yoga” in any meaningful sense? Yet I promise you that practicing Mountain Pose, even for a minute or so, can leave one feeling more grounded and more attentive, with a more solid foundation from which to continue your day (22). When you stand and know you are standing — when you really give yourself a chance to feel your way into this posture — and into the ground in an embodied way — you will feel a shift.

Dr. Balkarana writes that Mountain Pose is “no ordinary standing…. This is the standing of trees, of pyramids, of mountains.” In Hindu mythology, Mountain Pose invokes the god Shiva, who along with Brahma and Vishnu, is a member of the Hindu divine trinity. Like the god Shiva, “mountains are grounded, secure, enduring, majestic. He is the yang principle to support the yin of flowing Shakti energy. He is the riverbed without which the river could not flow” (25).

I should mention that as someone raised in a theologically conservative Christian context, when I first took up practicing yoga, I understood it in ways that were almost completely divorced from Hindu traditions. In some ways, I am grateful that the secularization of yogic and Hindu concepts and practices into the West has allowed yoga to infiltrate into even very culturally-conservative areas. And I celebrate whenever individuals and groups open themselves to learning more about the foundational Hindu spirituality that lies at the root of yoga.

For our second pose, let’s make a slight shift of our arms into “Prayer Pose” or Pranamasana. Here, with our bodies’ gestures, we are cultivating “reverence, centeredness, and inwardness” (136). In Hindu mythology, the Reverence Pose invokes the god Hanuman, who is an ardent devotee of the god Rama:

Whomever and whatever form our guru [our teacher] takes, we are called to respect them if we are to succeed in receiving all that they have to give. [Respect does not mean mindless or unquestioning obedience]. This posture naturally brings our attention to the heart center, so crucial for the mutual devotion flowing between teacher and student. (139)

For our third pose, let’s take it up just a notch to promote further skill in balancing with Tree Pose or Vrikshasana. With this pose, we are embodying and cultivating greater connection, stability, and openness to growth (160). It’s importance to emphasize that with yoga, poses are not about performance, but about experience.

From the perspectives of the Hindu Tradition:

Tree pose is simple, but for those who know the great wisdom behind it, it is among the most profound of yoga poses. In this pose, one’s hands are clasped, closing the circuitry of the heart energy. Also, one’s two legs become like a single grounding rod, connecting with the earth. The upright plane between [sky] and earth is divine…. It is the plane of kundalini [divine feminine energy] rising, of spiritual ascension, of touching the [transcendent] while rooted on earth. (163)

Our fourth position, Dog Pose or Svanasana, will likely be familiar to anyone who has visited a yoga studio. In many yoga traditions, it’s a position returned to repeatedly throughout the practice. It will also be familiar to dog owners since most dog breeds naturally bow at various times into “downward dog.” Like its canine namesake, this pose embodies and cultivates loyalty, ferocity, and power (34).

Mythologically, this pose is another one where Shiva is invoked. Dr. Balkarana writes:

Shiva is sometimes called the “Lord of Beasts,” because his refined consciousness is said to effortlessly tame wild [animals]. Upward facing dog has to do with working with the wild canine energy… The head is above the heart, activating the upward flow of kundalini. Downward Dog is a calming pose. It offers the grounding presence and companionship of a tame and loving dog. The head is below the heart, grounding into the earth. (37, adapted)

If this or any other yoga pose becomes too difficult, many teachers will invite their students to return at any point to Child Pose or Balasana. Spiritually, Child Pose invokes Krishna, an avatar or incarnation of Vishnu, a member of the Hindu Trinity mentioned earlier. Krishna symbolizes divine play, and this pose embodies and cultivates “grounding, safety, and serenity” (81).

Dr. Balkarana writes:

One important concept in the world of Indian philosophy is that of lila, which means “play.” This doctrine views mundane reality as resulting from the play of the Divine…. Play occurs when children feel safe and lose themselves in the moment. We have much to learn from children in this respect…. When engaging in this pose, connect with the calm grounding of a child who feels safe, content [and protected]…. (83)

At the risk of shifting too radically away from Child Pose, I want to go deeper into at least one more pose, one of the wild, advanced yoga poses I mentioned earlier. This one is a hand-balancing pose called Astavakrasana. Here you are cultivating “focus, skill, and equanimity” (202). A surprising number of people can do this pose.

In Hindu mythology, Ashtavakra is said to have been a sage of great wisdom, who was often misjudged because of his physical appearance. Dr. Balkarana writes:

The story of Ashtavakra teaches us the importance of humility…. Blowing someone else’s candle out doesn’t make yours shine any brighter. Rather, it diminishes the light available to you. Th tale is also an important reminder that appearances can be deceiving. Ashtavakra was judged prematurely on the basis of his age and appearance, to the detriment of all concerned. Any such prejudice…only serves to block us from experiencing the divine gifts that every person has to offer the world…. [This pose] challenges us to find the comfort in the discomfort and be of poised mind no matter how bent out of shape our circumstances may be. (205)

I would be remiss if I didn’t end this talk with the Corpse Pose or Savasana, which is often the final posture of many yoga practices:

Lying on your back on the floor, relaxing and releasing as completely as you can, you are cultivating inner stillness (49). At the end of a long, sweaty yoga practice, perhaps you remember being in Corpse Pose and feeling that sense of your “self” melting away, if only for a few moments, allowing you to just be. Don’t miss the allusion to ego death in that name, “Corpse Pose.”

This pose is another one which invokes the god Shiva, not surprisingly since his title is “The Destroyer.” There is a story of a time when the goddess Kali withdrew her presence from Shiva. Without Kali’s Shakti (her “divine feminine energy of play” and its relationship to desire) Shiva became little more than a corpse. The invitation then with this pose is to “cease becoming for a while, and embrace being. Through the practice of divine inertia, the capacity for witnessing from stillness can come to accompany you, even as you move through the turbulence of daily life” (49).

In this post, I have shared with you only the kernel of the stories behind each pose. If you are curious to learn more, there is much more detail and many more stories and poses — in Dr. Balkarana’s book. For now, I’ll leave the last words to him about how we each can continue to apply some of this ancient wisdom from the Hindu tradition:

What have you learned about yourself? Others? The world? Yoga? Like any great teacher, these stories will meet you where you are, and take you to a higher vantage point. And they will do this over and over, no matter how many times you revise them. They mirror and point to the mysteries of life, and the path to greater vistas of awareness.

Which of these stories stays with you the most? Which stories resonate most? Why? Which characters do you identify with most? Why? What impact have these stories had on your yoga practice? Your mindset? Your behavior?….

At some stage, once you feel you’ve integrated a particular story into your awareness, try your own retelling of it in the moment. Which aspects do you stress? What innovations do you make?… Enlivened in this manner, these stories will continue to inspire, entertain, and enlighten their tellers and hearers alike, as they have for ages past. (218)