KANDI SUBDIVISION

Charles Johnston

January 1890

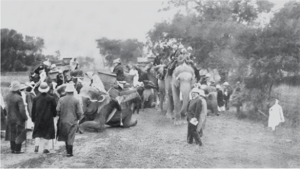

The Civil Station celebrated the Nativity by a tiger-shoot and a pig stick, under the auspices of His Highness the Nawab, and half a dozen of his big gray elephants; and I believe there was an exotic Christmas tree at the silk kuti at Babul bona.[1] Thereafter, in the cool days the turn of the year, I set forth rejoicing now in the rank of Deputy Magistrate and Deputy Collector, enhanced salary, and the power consign my Aryan brothers to durance, to rule over Kandi Subdivision, a kingdom of some quarter of a million souls.

(Top) “At Murshidabad” (Bottom) “Crossing the Bahigarati.”[2]

The road to Kandi lay through a marshy tract of bheels and jheels, where lean fishermen paddled in ladle-shaped canoes, hollowed from the bulbed butt of a fan palm, and cast their nets with a circular throw, gleaning a few poor little fishes for supper. Incidentally, I have known a group of Jaina capitalists buy up the fishing of the Bhagirathi River for many miles, avowedly in the interest of the poor little fish, and somewhat forgetful of the well-being of the fishermen.[3] The Bhagirathi River was now a shrunken blue ribbon in a wide valley of yellow sand with rows of stakes set and there for the nets of the fishermen.

Rounding the big mango tope with its pleasant memories of camp, we drove into the town of Kandi and came to a halt at the little square Board-of-Works bungalow, destined for two months to be our headquarters. It was in a rather deserted-looking part of the town, with red-brick houses up the road a hundred yards away, and the native College, for the making of young Bengali babus, somewhat nearer on the other side, in a garden of coral-blossomed ashoka trees. The bungalow had one large room, opening on a front veranda, and four small ones; with camp-cots, deck-chairs, and blue cotton carpets, the two Punaswamis, and their aides, soon made it presentable; and we settled down to rule a unit of the British Indian Empire.

The brand-new Deputy Magistrate plunged that same evening into the hundred activities of subdivisional life; first betaking himself in white-helmeted dignity to the cutcherry, to take over charge of the court and treasury, opium room, and jail, from the departing Soshi Babu, whose heart already glowed with glad anticipation of visits to his many fathers-in-law.

Soshi Babu, besides being Deputy Magistrate of the Subdivision, was Chairman of the municipality of Kandi, a kind of small lord mayor; so, in his uxorious absence, these cares also, and they were heavy ones, descended upon the shoulders of the incoming Deputy Collector.

One of the drove of big dogs that lolled and snoozed and scratched under the arches and along the streets of Kandi, went mad and, in a paroxysm of folly, bit a municipal policeman, one of a score of red-turbaned knaves under my immediate orders. Thereafter the said mad dog, realizing, I suppose, that it was all up with him, in true Eastern fashion ran amuck, biting and snapping at his colleagues till the whole bazar was a canine pandemonium. Having suffered in honor, the Deputy Magistrate now got his opportunity for revenge on the pariah dogs.

The policeman came wailing to me, and exhibited his wound; Bengalis love to show their wounds. It was a mere scratch on the shin, but the man was half crazy with fright. So I sent him to the subdivisional surgeon, a Boidhyo, a man of the doctor caste, with a shrewd diagnosis and a healing touch, to be cauterized and comforted; and then, as Acting Chairman of the municipality of Kandi, I issued a Hukum, proclaiming a wholesale massacre of stray dogs, and binding, as I remember, the said municipality to pay a reward of eight annas for each dog so slaughtered.

In my inexperience, I made a slip. I should have included in the proclamation a clause directing that the dead dogs above-mentioned and therein aforesaid should be delivered to one of my subordinates conveniently far off—say the bitten policeman, who would have enjoyed it—for due enumeration. I forgot to do that, so they brought the dogs to me.

An ox-cart load of them in the daytime was bad enough; but it was abominable to be awakened after midnight, to take cognizance of slaughtered corpses and sign an invoice of dead dog. Even in death, those beastly pariahs had the better of me.[4]

← Table Of Contents →

SOURCES:

[1] There was also a performance of Jacques Offenbach’s “Les Deux Aveugles,” performed by Ritchie and Page, “the only actors in [the] tiny community.” [Ritchie, John Gerald. The Ritchies In India: Extracts From The Correspondence Of William Ritchie, 1817-1862. J. Murray. London, England. (1920): 370.] On a sadder note, the Johnstons were likely made aware of the death of Pandit Bhashyacharya. In 1889, he again fell ill. This time, however, “neither the entreaties of his friends nor the advice of his doctors could induce him, until it was too late, to go away from the Library.” He died on December 22, 1889, in the home of his brother in Madras. The immediate cause of death, it was said, was “blood poisoning from carbuncle in the hand.” [“Death Of Pandit N. Bashya Charya.” Supplement To The Theosophist. Vol. XI. (January 1890): 7.] In his will, he left to the Library his private collection of palm-leaf manuscripts, which would form the nucleus of a fine collection. [Olcott, Henry Steel. Old Diary Leaves: Volume IV. Theosophical Publishing Society. London, England. (1910): 210.] Gopalacharlu (Bhashyacharya’s adopted son) was appointed Treasurer of the Society, but that would ultimately end in tragedy. [Olcott, Henry Steel. Old Diary Leaves: Volume IV. Theosophical Publishing Society. London, England. (1910): 240.] In 1893 Gopalacharlu stole over Rs. 8,649 of Society funds. He ended his life with poison when he was about to be discovered. [“Theosophical Items.” Light Of The East. Vol. II, No. 6 (February 1894): 175-177.]

[2] “At Murshidabad.” Bengal: Past & Present. Vol. II, No. 2 (April 1908): 202; “Crossing The Bahigarati” Bengal: Past & Present. Vol. II, No. 2 (April 1908): 202.

[3] Johnston, Charles. “The Early Races In The Popol Vuh: Pt. III” The Theosophical Forum. Vol. VIII, No. 9 (January 1903): 162-165.

[4] Johnston, Charles. “Helping To Govern India: Kandi Subdivision.” The Atlantic Monthly. Vol. CIX, No. 2. (February 1912): 265-273.