NEVERMIND THE BABU.

Charles Johnston

Late November 1889.

“Sir! Do you not know me?”

I looked closer.

“I am Okhoy Kumar Ganguli, pleader of your Honor’s court.”

“Ah! Okhoy Babu! He flashed back into my memory, as he had disappeared in a cloud of dust down the village road, on the day of the perjury case. With equal rapidity it flashed in to my mind that if I wanted to get the Babu clear, I must show no sign of ever having seen him before. So I shook my head and turned away to the fine old graduate of Berhampore jail.

“The Manjhi Than.”[1]

We took our seats in a circle in the grove, on stools of wicker-work shaped like dice-boxes. I recognized the pattern. We have them made on contract in the jail. Evidently the old headman had brought the arts back with him. I sat in the center of a half-circle, made venerable, I hoped, by a big pith helmet. The old headman, whose name, I believe, was Sundra Manjhi, sat at my right hand; the stalwart men with spears, gaudy in their peacock-feather crests, completed the half-circle.[2] At its focus Okhoy Babu squatted on the earth, with a knot of spear men about him. He was tightly bound and evidently galled by his thongs. I pitied Okhoy Babu. It remained to be seen whether I should not very soon have even better cause.

The women gathered closer, fine looking, some of them, and not so cowed and abashed as Bengali women. Most of them had flowers in their hair. They had brass bracelets and rings, too, and bright-colored muslin saris—a long strip of cloth, draped into a skirt and bodice, that showed their fine, graceful, upstanding figures admirably.

But Okhoy Babu was not thinking of feminine beauty or adornments of Ashoka flowers—at least his face did not suggest it. It was grim earnest with him. I would do my best for Okhoy Babu, but I had my doubts.

We opened the proceedings. The old gentleman stood up and made a little speech in Santali. I guessed the subject: their exceeding good-luck in having caught a magistrate, albeit a very young one, whose presence would regularize their proceedings. I knew he was talking about me, as everyone looked in my direction and the women smiled. The men were too dignified for that, but their big, childlike eyes spoke.

Then old Sundra Manjhi turned to me and said—

“Your Honor, we are ready,” in his best Bengali.

Okhoy Babu winced and shrank together. Evidently, he was not ready at all.

So, as severely as I could, I asked—

“Of what is the prisoner guilty?”

“Your Honor!” Okhoy Babu began, in English. That would be fatal. So I said to him, in a tone that evidently went home—

“Don’t talk to me, you thundering idiot, if you wish to save your neck!”

Okhoy Babu sighed deeply, but had the wisdom to shut up.

So I asked again—

“Of what is the prisoner guilty?”

“Your Honor,” said the fine old Santali, with genuine moral indignation, “the Babu told a lie.” He came to us, one month ago, hungry, and sick. We sheltered him and fed him. After two days, he began to make mischief! There are the boundary stones; they mark the limit of our territory and the territory of the Bengalis. This Babu told us he would show us how to move the boundary stones—secretly, in the night—so as to enlarge our lands and double the size of our rice-fields. The Babu is a cheat and a liar, so we are, of course, going to kill him.

Oh, tribe of honest men! I like those Santalis. And the fine Italian hand of my Okhoy Babu! He ran like a hare to escape trial for perjury, in the matter of that coconut, date, jack, and so-on tree in the field of Hari Dass, and straightway set himself to seduce the blameless Santalis and lead them into guile.

Babu, for two or three minutes, I seriously considered saying, “Let the law take its course!” Perhaps what checked me was the consideration of how you would squeal while you were being speared. At any rate British legalism won the day, and I determined to save you for a more regular tribunal.

How to do it, though? I thought first of trying to explain the English law, making clear to them that they would be guilty of murder and riot and dacoity and ever so many things. Then I thought of asserting the right of eminent domain over the Babu—of claiming him as my own peculiar prey. But I was pretty sure they would ask, “Will your Honor promise to kill him?” And various considerations would prevent my doing that. To get him away by strategy just entered my mind, to leave it again instantly. I could not risk having these honest men hand down among their village traditions, that they had trusted a white man and that he had cheated them.

Then I noticed something curious enough—but the nature of woman is inscrutable.[3]

A singularly pretty girl, light-colored, with pretty eyes and quantities of glossy hair decked with crimson flowers, her lithe, graceful young body charmingly set off by the sari with its pattern of rose-colored twigs, had been edging closer to Okhoy Babu and now, eluding the vigilance of the guards, she gave him a coconut shell of water, which he greedily drank, and—oh, mysterious feminine heart!—she was patting his cheek. I began to see daylight.

The first thing was, to gain time. So I made a quick decision and, rising, said in my best Bengali—

“The Babu is evidently a wicked man, and deserving of death. He has lied, and he has advised you to lie. But today is the seventh day of the moon”—fortunately I had noticed the evening before—”and this is, therefore, an inauspicious day for you to put the Babu to death.”

That was true enough. Any day would be, for they would have to stand trial for murder, and very possibly hang for it. But they did not take my words in that sense. Indeed, they looked genuinely frightened. They were chock full of superstition, and they had nearly killed a Babu—on the wrong day![4] They were genuinely glad that I had come. I saw that, and went on confidently—

“Not before the tenth day will time be auspicious. Therefore let Babu be left bound in a hut, with none to keep him company, and let us wait until the auspicious day. Meanwhile, if the village wishes to hold a feast honor of the Sahib, the Sahib will graciously be pleased to take part in it.”

The joy, the feasting, the rice-wine generously flowing, the wild song dance—all this must go unrecorded.[5] Babu Okhoy Kumar Ganguli was present at the feast. He languished his cell—that is, in a leaf hut at jungle-edge of the village.

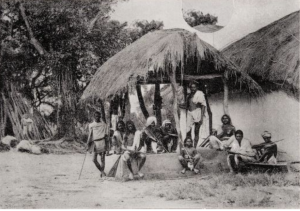

“A Santal Dance.”[6]

That night, after a long day’s revelry, the village slept well. All, that is, excepting the Deputy Magistrate, who kept an alert ear, and, it would seem, that pretty girl with the crimson blossoms in her hair. Early in the night the Deputy Magistrate, who was enjoying the moonlight, as the sentries snored over their fires, saw a lithe figure steal over to the prison-hut. Then there was silence, but for a faint sound of rending leaves; then the Deputy Magistrate went to his own hut, for matches, and smoked a philosophic cigarette. Then he went to sleep.

Babu, I hope you have good legs and wind, for an hour after sunrise your inexplicable absence was discovered; the absence, too, of that pretty girl with the crimson flowers in her dark, glossy, hair. I hope your legs and your wind are good, for, ten minutes after these discoveries, forty able-bodied Santalis, whose power of wind and limb was unquestionable, were on your trail, armed with boar-spears. And I think, that if they caught up with you, they would finish you without benefit of magistrate!

Shortly thereafter, I succeeded in scraping together half-a-dozen hoary-headed men, past the age for Babu-baiting, who consented to carry my palki, and, with sincere regret, I bade farewell to the Santal country; regret, in part, for that I had in fact contributed to deceive these honest men for such a one as Okhoy Babu, procurer of perjury. But not for the sake of Okhoy; for the honor of the law.[7]

← Table Of Contents →

SOURCES:

[1] Bradley-Birt, F.B. Chota Nagpore: A Little Known Province Of The Empire. Smith, Elder, & Co. London, England. (1910): 116.

[2] On June 30, 1855, an army of ten thousand Santali rebels took an oath in Bhagnadihi village to fight the exploitation of the mahajans, zamindars, and the other corrupt officials. They decided to march to Calcutta, the capital of British India. In September, three thousand Santalis, led by Muchia, Komna, Jele, Rama and Sundra Manjhi captured and burnt a few police stations, and pillaged neighboring villages. They managed to liberate a wide area on the eastern side of the Ganges, ranging from Bhagalpur in the north, to Grand Thiunk Road in the south, and up to lindi pargana in the west. On November 10, 1855 martial law was declared in Bhagalpur, Murshidabad and all over Birbhum, which was effective in the region until January 3, 1856. Eight thousand British soldiers were posted in the region, and a separate, non-regulation district of Sonthal Parganas came into being as a result, and was placed outside the jurisdiction of the regular courts, general laws, and regulations. The Sundra Manjhi mentioned by Johnston may be the same man who participated in the 1855 uprising. [Ghosh, Arunabha. “Jharkhand Movement In West Bengal.” Economic And Political Weekly. Vol. XXVIII, No. 3/4 (January 16, 1993): 121-27.]

[3] According to Johnston, life had set up for women “the standard of the immortal soul, with its power, its gladness, its penetrating beauty, and its everlasting mystery, which no faith or philosophy has ever perfectly understood.” [Johnston, Charles. “Count Tolstoy At Home.” The Arena. Vol. XX, No. 4 (October, 1898): 480-490.] Elsewhere Johnston states that women seemed to have an “inborn and incommunicable excellence in matters as spirituality and idealism, and the divining of that finer world which is nonetheless real because it is invisible.” [Johnston, Charles. “A College Of Ideals: An Impression Of Bryn Mawr.” Harper’s Weekly. Vol. LIII, No. 2746. (August 7, 1909): 16-17.]

[4] The Santal had no conception if a supreme beneficent God. Their religion was one of terror. Hunted and driven, from country to country, by the other peoples of India, they could not conceive how a Divinity could be more powerful than themselves, yet not wish to inflict them harm. Though the Santal had no God for whom to appeal, they believed in a multitude of demons and evil spirits whose wrath they endeavored, by supplications, to avert. A firm belief in the near presence of an unseen world populated with a host of demons, ever at hand, to punish the wicked, scatter diseases, spread murrain among the cattle, blight the crops, and were only appeased by the outpouring of animal blood. Far from lacking religion, Santal rites were, in fact, more numerous than those of the Hindu. [Hunter, William Wilson. The Annals Of Rural Bengal. Smith, Elder And Company. London, England. (1897): 215-218.]

[5] Little was known of Santal culture because so few outsiders were permitted entry into their villages. Those who had been guests of the Santal, however, spoke of the unparalleled hospitality which the Santal showed towards strangers. Every occasion was seized upon for a feast, where an abundance of game compensated for the absence of traditional luxuries. Santal women enjoyed a degree more freedom than their Bengal counterparts, and participated in festival; they danced slow and decorously—joining hands, and forming themselves into an arc of a circle, and advancing and retiring towards the center where the musicians performed. The only noticeable display of male preference was the custom of the men finishing their meals before their wives began. Santal maidens, however, held an extraordinary privilege when it came to claiming her husband and lover. All she had to do was take a dish of prepared rice. The man had to eat it, and was bound to marry her. [Wardle, Thomas. “History And Description Of The Growing Uses Of Tussur Silk.” Journal Of The Society Or Arts. Vol. XXXIX, No. 2,012. (June 12, 1893): 608-651.]

[6] Bradley-Birt, F.B. Chota Nagpore: A Little Known Province Of The Empire. Smith, Elder, & Co. London, England. (1910): 128.

[7] Johnston, Charles. “Okhoy Babu’s Adventure.” The Atlantic Monthly. Vol. CXIV, No. 3. (September 1914): 309-316.