BELGAON

Charles Johnston.

Early November 1889.

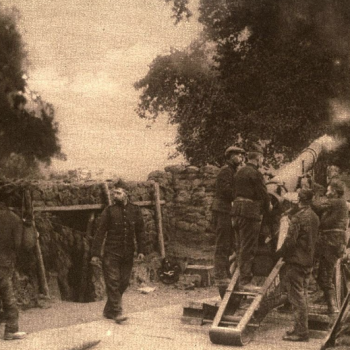

It was a heartening sight in the approaching twilight, to see the servants and orderlies, aided by impressed village watchmen, clearing a fair space for the camp, under shady mango trees at the village of Belgaon. They scraped the sandy soil clean, laid on it a thick layer of sweet-smelling rice straw, and spread on this blue-and-white cotton carpets. In the center, they laid the butt of the big tent-pole, shook out the skirts of the tent, and then hauled away, unfurling the tent within a tent, a square home of canvas with a pyramid roof and an-air space a yard wide between the inner and the outer tent. This, with the ample shade of the glossy mango boughs, keeps one from roasting in camp in the “cold” season: cold enough, that is, for peaches to hold something of their flavor, but too hot, even at Christmas, for strawberries, save on the mountain-tops about Mussurie.

Setting Up Camp. (Source: Old Indian Photos)

The wings of night were spread over Bengal. The moon poured white showers through the darkness, silvering the rice-fields, that faded away to dim infinitudes, under a pale blue veil of mist. Our tents, now pitched, stood ankle deep in their own shadows in a grove of mango trees. The moonlight sparkled on the glossy blackness of the leaves, and fell in white splashes on the canvas. Ghostly figures of watchmen snored beside the ashes of their fires, their spears resting against the tree-stems. A stillness throbbed over all. Suddenly the veil of silence was rent in pieces. A piercing shriek came out of the mist Another answered it, from far off, then another. Then shriek followed shriek on all sides, quick, ear-splitting, horrible, full of tortured and tormented wailing. The air was shattered into short waves of terror, that changed slowly into mocking laughter, and then vanished in sudden silence. The jackals were gathering in the rice-fields.

The moon looked down upon the night; she even peeped within my tent and smiled an inscrutable Eastern smile. Outside it was cold enough, and the coats of the jackals were wet with dew. But I did not feel cold within the double shelter of my tent. I sat on my camp bed with my feet tucked up, feeling oppressively hot; I was thoroughly down-hearted and wretched. The mosquito curtain let down round my bed seemed a cloud of black melancholy, instead of white gauze. The figured brown lining of the inner tent looked dull and dispiriting. The lamp seemed to radiate heat on my hot back, and the whirring wings of the fans in its draught-chamber tormented me. I was dressed in a Jaeger vest and hose, for coolness, and my feet were bare. Yet I was heated, red-faced, and disconsolate. Desolation was heavy upon me, and jackal-voices were howling in my heart. I felt like a little child left alone in the dark; I felt as if all my friends were dead, and as if I hated everybody. I tried to think of my mother, and of the consolations of religion, and of my soul; but only to decide that it would probably not be saved, and that I no longer cared. I felt utterly deserted and alone, with that ghostly world of chill mist all about me, where the jackals howled, in the dim and gruesome vastness of the night.[1]

Theo had a charming way of coming to my tent in the cool of the morning, calling me till she saw my eyes open, and then saying in her pretty Hindi

“Johnston, hamare sung kelo!” which is to say, “Come play with me!”

She had picked up my name from her great big papa, the Collector Sahib.

The glossy depths of the leaves were full of the contralto gurglings of golden orioles; now and then they flamed across a bar of sunlight. In the crown of one huge tree a heavy-winged vulture had her nest, while her mate soared and circled, a speck in the illimitable blue. Streaked squirrels frisked hither and yon, chattering sarcastic disapproval of rude British ways. Our tents, as big as cottages, whitened the vast green shadow of the mango grove. The horses stamped contentedly beneath the boughs.

Echoes of a noisy dispute came from the servants’ quarters. A loaf of bread was missing—a serious matter in camp. Punaswami of the crimson and gold turban, accused Punaswami the second, of stealing it. Punaswami the second said a jackal had taken it, which happened to be true. But the elder Punaswami sneered.

“A jackal eat bread?”

“A jackal will eat anything,” retorted the angry butler, “even the flesh of a cook.”

And so the swarm of turbaned bare-footed servants gossiped and quarreled in their quarters, deftly performing their tasks, and going their crafty inscrutable ways.[2]

In the dew-bespangled sunrise, while the air was caressingly cool, we went forth to ride along the river bank and beside fields of yellow mustard or dun stubble; then, on our return to the shadowed tents, a bath, breakfast, and the day’s occupation.

I had my office-table set up under the trees, and summoned the weighty men of the village to give an account of their doings and their people. They came, reverend seniors, elected by the householders of those reed-thatched mud-houses, to form the Council of Five, signified by their title of Panchayet. [3] Very good men they were, with much native mother-wit, palpably well-chosen and thorough masters of their duties—the settling of village disputes concerning lands, the division of the fruits of harvest between communal tillers, the levying of village rates, the payment of the watchmen—those indigo-coated, white-turbaned chowkidars with their pikes, who had snored the night through over the ashes of their campfires, as the jackals flitted among the ropes, and night-owls hooted in the branches.[4]

“A Visit To The Camp.”[5]

I had the indigo-coated chowkidars up before me, in an abashed row, and made them testify as to the peace the village; then I looked over their wage-books to make sure that each them got his five rupees a month regularly, lest they might fall into thieving. When I had duly verified these things, going over one grubby booklet after another, making out the crabbed entries in village Bengali, and cross-questioning the illiterate chowkidars, to check the written figures, I came to the conclusion that the village accounts were honestly and effectively kept, and that the Bengali village was a model of good local government. Its structure is, indeed, by all odds the oldest thing we have in India; older by ages than the British Raj, older than the Mughal invaders whom “John Company” superseded, older than the era of Persian and Arab raiders, older than Chandragupta or Ashoka, older than the venerable laws of Manu, son of the Sun.

Impressed at finding myself in the living presence of this fragment of an elder world, I relieved the tension between two ages by having the chowkidars drawn up in line, and putting them through marching and pike exercises, to the ecstatic admiration naked little Bengalis of both sexes, who had mysteriously found their way to the Sahib’s camp, and were peeping like big-eyed brown fairies from behind the smooth boles of the mango trees.

Then I read petitions about all kinds of little local ills; gorgeously worded petitions, in which I was addressed as Dharmavatar and Garibparwar: Incarnation of Righteousness, and Umbrella of the Poor. One can do much to lift heavy burdens in this summary fashion, and, on the whole, I think I got at the truth. It was borne in upon me, and often verified thereafter, that the life of these humble Indian villages is, on the whole, very happy, despite superstitions and lean days and a climate exasperatingly hard. We of the British Raj shield these poor folk from battle, murder, sudden death, if not always from plague, pestilence, famine; we guard them against rapacious, lazy overlings, who have preyed on them from generation to generation, and who pay us in angry discontent for thus interfering with their prey. These villagers and their like have learned by experience that they can trust implicitly in our law and even-handed justice. No small thing, this, to do for nigh three hundred millions of the poorest, most defenseless folk on earth.[6]

Then again, in the swift dusk of evening, when furtive jackals rent the twilight stillness with wailing and demoniac laughter, or the silver bark of little foxes echoed over the mist-veiled rice-fields, white under the moon, we gathered in comfortable deck chairs in a great, dim aisle of the mango grove, while the tents shone orange in the lamp-light, to tell sad stories of the deaths of kings, or listen to Castle, the Police Chota Sahib—who had a pretty sentimental tenor—sing “The Long Indian Day.”[7]

← Table Of Contents →

SOURCES:

[1] [This description is from Johnston’s novella, Kela Bai.] Johnston, Charles. Kela Bai: An Anglo-Indian Idyl. Doubleday & McClure Co. New York, New York. (1900): 39-41.

[2] [This description is from Johnston’s novella, Kela Bai.] Johnston, Charles. Kela Bai: An Anglo-Indian Idyl. Doubleday & McClure Co. New York, New York. (1900): 82.

[3] Johnston writes: “There were, in every district, at least four types of bodies having activities that were genuinely legislative. Beginning with the simplest, there was in every village the elected Panchayet, lineal descendant of the self-governing body in the age-old village community. Next came the elected local board, for each subdivision, not indigenous, but quite recently overlaid on the native life by the British administrators. Then there was an elected district board, with supervision over roads, bridges, hospitals, and schools, and with power to raise local taxes. These district boards had in them the germs of the county councils of modern England, themselves remote successors of the Saxon shire mote. Finally, the municipalities were governed by elected bodies, predominantly native. So there were elements of self-government in India, as well as opportunities for qualified natives to share in the daily work of administration. All these elements might well have developed along indigenous lines.” [Johnston, Charles. “A Perspective On India.” The Atlantic Monthly. Vol. CXXXVIII, No. 6. (December 1926): 848-856.]

[4] In late 1889, Steuart Bayley thought it desirable to examine the working of the rural police generally. He decided to depute an officer who was conversant with the working of the Village Chowkidari Act (Act. I.B.C. of 1886,) Colonel H.M. Ramsay on the special duty of gathering as complete information as possible regarding the way in which the rural police was generally worked in each district of Bengal, and of devoting special attention to the chowkidars employed under Act. I.B.C. of 1886. [“Occasional Notes.” Englishman’s Overland Mail. (London, England) February 25, 1890.]

[5] Compton, Herbert. Indian Life In Town And Country. G.P. Putnam’s Sons. New York, New York. (1904): 162.

[6] Johnston, Charles. “Helping To Govern India: Kandi Subdivision.” The Atlantic Monthly. Vol. CIX, No. 2. (February 1912): 265-273.

[7] The “Long Indian Day,” was a popular parody of the German song, “The Long, Long, Weary Day.” It was penned by the anonymous “Mario,” and published by Rose of Bombay in 1889 (just after the Johnstons arrived in India.) The lyrics were: “Thus on from day to day, Wags the long Indian day. Until grown old and grey, We get one pound a day, And totter home to die in England. A worthy recompense, For loss of health and sense. Thus ends my story, Of soldier’s glory.” [Compton, Herbert. Indian Life in Town and Country. G.P. Putnam’s Sons. New York, New York. (1904): 228-229; Winstock, Lewis S. “Rudyard Kipling And Army Music.” The Kipling Journal. Vol. XXXVIII, No. 178. (June 1971): 6-12.]