OUT-OF-DOOR-LIFE

During the colder months (November-March) many Government officials were required to travel about their districts on inspection tours in the execution of their ordinary responsibilities. In Herbert Compton’s Indian Life In Town And Country, he states:

Out-of-door life in India may be divided into three categories. First of all there is the life known as “going into camp,” or “on tour” which many Government officials are obliged to follow during the cold weather in the execution of their ordinary duties; then the habitual open air employment of engineers, forest officers, planters, railway employees, and so forth; and lastly, out-of-door life in the shape of sport and recreation.

From the beginning of November to the end of February or March as much of Anglo-India as is able keeps in the open, to make up for those eight weary months of confinement, during which it has been imprisoned under punkahs and bottled up in bungalows. This is the season when the Government officials travel about their districts on inspection tour, which, to those who like riding and shooting, is the most enjoyable of all the various phases of duty.

Camping life is, indeed, a delightful institution of India. The itinerary of the district tour is mapped out, and preparations are made for a three or four months’ gipsy existence under the skies, but accompanied with the refinement of comfort which the Anglo-Indian knows so well how to secure under such conditions; for tent-life has been brought to a high pitch of luxury. The camp equipage will consist of a big office tent, and a couple for dwelling in, with accommodation for the servants. There will be bullock-carts, or camels, to carry the baggage, including the most ingenious articles of camp-furniture, which can be telescoped or folded into portable dimensions. Indeed, you will sometimes see superimposed on a couple of camels a variety of beds, tables, chairs, and chests of drawers (these take into halves, and are slung one on each side,) which, when opened and set out, suggest the requirement of a small pantechnicon van for their removal. Generally a portion of the poultry-yard is carried during these excursions, and a goat or two driven along to supply milk. And when the camp is pitched under a shady mango tope, or grove of trees, the dhurries or carpets laid, the ingenious collapsible furniture arrayed in its expanded usefulness, the camp-lamps shedding their bright glow within the tent, a crackling fire blazing in front of the door, why there are very few habitations for which you would wish to change this travelling one.

The cold-weather tour of the head official of a district, who is in effect its governor, is a sort of triumphal progress. He lives on the fat of the land; at his nod transport and provisions of every description appear in plenty; for him, the best khubber where game is to be found, and beaters galore to drive it out of its haunts. At each halting-place the headman comes to offer him welcome, and the finest the village can afford, and all the ryots assemble to make their salaams. His tour is like an old English “visitation,” and, if an energetic officer, he probably does more good in his district during these few cold weather months, when he is brought face to face with its requirements, than during the rest of the year. For they bring him into touch with the people in a way that can never occur in station life.[1]

Regarding the dramatis personae of camp, Johnston writes: “We were a goodly company; the Collector and the Assistant Collector, with Mem-Sahibs and a sister-in-law; the silk-kuti Mem Sahib and her chunky baby; the Police Burra Sahib and the Police Chota Sahib; and […] Theo.”[2]

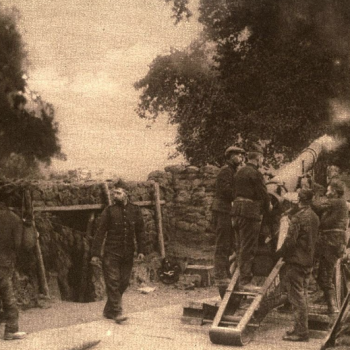

Camp. (Source: Old Indian Photos.)

The Collector and Assistant Collector are Ritchie and Johnston, and the Mem-Sahibs are Verochka and Margie Ritchie, the latter having recently returned from Darjeeling with Theo. A month earlier, in October 1889, Theo made her second appearance at Dr. Lethbridge’s costumed “Children’s Ball,” where she dressed as the “Queen of Hearts.”[3] (The previous year she was a fairy.)[4] The sister-and-law is likely a reference to Anne Thackeray, and letter from Edith Sichel places Anne in India at this time.[5] Anne’s latest piece, “The Boyhood of Thackeray,” would be published in the December 1889 issue of St. Nicholas magazine, and provided some accounts of the Ritchie/Thackeray family in India. Perhaps the nature of her visit was one of research.[6] The “silk-kuti Mem Sahib and her chunky baby,” was probably Jeanne-Cecile Gallois and her child, and while there is no reference to Alphonse, Eugène was present. The Police Burra Sahib and the Police Chota Sahib were Meares, the District Superintendent of Police, and R. Castle, the new Assistant Superintendent of Police, who recently transferred to Murshidabad from Patna City.[7] Recalling his own experience in camp, Ritchie writes:

Theo went about in a bullock-cart on springs. She enjoyed camp life […] the playing about in the shade and round the tents. She had fits of mad cap merriment, toddling about and hiding behind trees. The volunteer sergeant’s wife, Mrs. Woody, was constituted her nurse. Woody had a fat cottage child—Mirrie and Mirrie and Theo were brought up together. They were a great contrast. Mirrie boisterous and bold, but an excellent companion, and Theo loved her, always giving in. W. H. Page, the judge, a genial, musical Wykehamist, chummed with us. He made Theo say absurd speeches, “I feel drawn to Page,” and to stand up and declaim.[8]

← Table Of Contents →

SOURCES:

[1] Compton, Herbert. Indian Life in Town and Country. G.P. Putnam’s Sons. New York, New York. (1904): 227-229.

[2] Johnston, Charles. “Helping To Govern India: Kandi Subdivision.” The Atlantic Monthly. Vol. CIX, No. 2. (February 1912): 265-273.

[3] “The Children’s Ball At Darjiling.” The Englishman’s Overland Mail. (Calcutta, India) October 8, 1889.

[4] “Dr. Lethbridge’s Fancy Dress Ball.” The Englishman’s Overland Mail. (Calcutta, India) October 16, 1888.

[5] Sichel writes: (To Anne Thackeray in India) Chiddinfold, late Autumn, 1889. I wish I could put as much news as love into this letter, but the Cot produces more content than novelty. Nobody is born, nobody is married, nobody is dead. We are so happy here that one longs for a little more lotus-eating. Three months without a ‘worree’ does spoil one dreadfully. However, London is always London and the marrow of one’s heart. We are all much excited by General Booth and his huge Utopian scheme. Oh lor! how I wish we could take third-class tickets to Utopia and carry off the whole of Whitechapel there.” [Sichel, Edith Helen. Letters, Verses, and Other Writings. Printed For Private Circulation. (1918): 50.]

[6] Ritchie, Anne Thackeray. “The Boyhood of Thackeray.” St. Nicholas. Vol. XVII, No. 2 (December 1889): 99-112.

[7] “Breach Of The Laltakuri Embankment.” The Englishman’s Overland Mail. (Calcutta, India) September 7, 1889; “The Bengal Services.” The Englishman’s Overland Mail. (Calcutta, India) October 8, 1889; “The Bengal Services.” The Englishman’s Overland Mail. (Calcutta, India) November 12, 1889; Johnston, Charles. “His Highness The Nawab: Helping To Govern India.” The Atlantic Monthly. Vol. CVIII, No. 4. (December 1911): 797-804; Johnston, Charles. “Helping To Govern India: Kandi Subdivision.” The Atlantic Monthly. Vol. CIX, No. 2. (February 1912): 265-273.

[8] Ritchie, John Gerald. The Ritchies In India: Extracts From The Correspondence Of William Ritchie, 1817-1862. J. Murray. London, England. (1920): 370.