THE TALE OF GUNGA RAM

Charles Johnston.

May 20 1889.

When the lesser rains began to sputter in the dust, things had already gone far with Gunga Ram. The peaceful tenor of his life had given way to troublous days.[1]

He might look back, but could no more go back, to the time when he was a happy Brahmin zemindar a landowner in the village of Belgaon, in the metropolitan district of Murshidabad. His wealth consisted of undivided quarters or sixteenths of small parcels of land, whereon sweltered dark-skinned Bengali ryots, tilling sugar-cane, or chopping mulberry twigs for their silkworms, or haply growing blue-cheeked brinjals, or more thrifty kolai. These scraps of ground were so intricately interwoven with others belonging to rival zemindars that the map of them in the Land Department looked like a bit of Persian carpet, or a Chinese puzzle with half the pieces lost.

Gunga Ram had been happy. At least he could look back to that. And the village folk revered him. Mud huts with reed thatch looked up adoring to his red brick kuti, on whose flat roof, behind a parapet of brick-lace work, the well-hid women of his household aired themselves in the cool of the evening.

Gunga Ram was a Brahmin. In his veins flowed blood consecrated by many centuries of sacrosanct tradition. As an ambassador of the gods, he was holy, inviolable. So he inevitably held himself of no common clay, but rather true kindred of the Devas; one whom to please by lowly service and prostration was aim enough in life, bringing merit in blessed worlds; while who should offend, or slight, or, haply, strike him, must pay penalty in chilly, interminable hells.

Taking it all in all Gunga Ram bore himself simply enough for so much divinity. He bullied browbeat his peasants mercilessly, but they felt a condescension, and revered him the more; he gathered to him a goodly number of little wives, hardly more than mere babies; but his excuse might been—had he dreamed that an excuse could be required—that the fathers of those deer-eyed, velvet-skinned little girls, Brahmins themselves, but of sanctity than Gunga Ram, had eagerly sought alliance with him, pressing their little daughters on him, as a viscountess might press her viscountess might press her daughter on a duke, young, comely, and of great possessions. Such a son-in-law as Gunga Ram brought merit through seven rebirths.

So they accumulated there, on the flat roof of Gunga Ram’s kuti, the deer-eyed little girl wives with their velvet skins; and one by one, they dutifully brought forth babies, when they themselves should have been making mud-pies in happy innocence. They were subdued, good little women, holding meekness their religion; fortified in this, indeed, by the grim old mother of Gunga Ram, whose face, yellow as parchment, wrinkled with innumerable lines, was framed in snow-white hair, smooth and sleek with no single ornament; she wore the white sari of widowhood, and mitigated her joyless days by visiting upon Gunga Ram’s meek little wives all the tyrannies she herself had felt in the days when she was a meek little wife under a despot mother-in-law.

While they endured the shrill scoldings of the grim old Brahmin woman, no doubt they looked forward in a dim way to visiting like scoldings upon other little wives when they themselves, through the passage of years and the bearing of many babies, should have graduated to the sovereign rank of mother-in-law. But all their meek little hopes were shattered, almost before they took form, and all their little world was rudely torn apart by wild doings they could, in their innocence, do little to control, and at which they could only stare in large-eyed terror, wringing piteous little hands.

Little could they do little could they dream doing, to curb the roving fancy of Gunga Ram; for was not his will their law, his favor their sunshine, his pleasure, wherever it might lead him, their sovereign good?

It did, in fact, lead him to a little street of houses thatched with reeds, on the north side of village of Belgaon. In this little street, in one the cleanest of the clay houses, under thatch immaculate, lived a certain woman whom we will call Ashoka, the Cure for Sorrow; for such, in her good-hearted way, she tried to be. She was beginning to age and wrinkle, though still young in years, for this is way of Oriental women; yet, because of her heart, her ready sympathy, and a certain charity in her, she had many friends; let us hope it covered the multitude of her sins.

Ashoka, true to her name, had, toward the cure of sorrow, brought into the world two pretty daughters, Kusuma, “the Blossom,” and Sundaree, “the Lovely.” Ashoka herself thought they had Brahmin blood in their veins. She taught them arts and graces, and, perhaps through that infusion of finer blood, perhaps through some principle of compensation, these two daughters of hers were gifted with a lively wit, an awakened spirit, a certain mirth, and humor, never attained, or even dreamed of, by their sisters who followed quieter, more ways.

Gunga Ram had some instinctive perception of this, and many a day he came to the north street of village to chat with Ashoka, enjoying always mirthful, keen, charitable judgments of men and things, and the impersonal wisdom of a life that left little place for personal self-esteem. Gradually fell into the way of chatting with Kusuma and Sundaree also; but though he spoke with equal gentleness to both, it was Sundaree who made her into his heart.

Ashoka smiled at this, in the beginning, very well pleased that the great man, whom, nevertheless, she treated with very familiar deference, should look with kindly eyes upon her girls; and Gunga Ram, a rich man in his way, as well as a Brahmin, never failed to bring presents to Sundaree, and to Kusuma also, lest he should manifestly appear to bring presents to Sundaree alone.

Ashoka first smiled, genuinely rejoicing at the favor shown to her pretty daughters; then she began to regard the matter more thoughtfully. She had good cause, for, by hardly distinguishable degrees, Gunga Ram came to bear himself not so much as the guest of her house—as which, he was, indeed, most welcome, and full of honor—but rather as in some sense its master. Little by little, while he still brought gifts for both, his passion for Sundaree palpably grew. If the thought of taking her into the well-ordered part of his life ever occurred to him, he must have dismissed it on the instant, with hardly even a regret, for the thing was wholly impossible; unthinkable even as a crazy fantasy. Such things do not happen, cannot happen, in immemorial Bengal.

The thought, then, never entered his head, or, knocking at the door, found there no lodgment; perhaps the whole matter was for him no subject of thought at all, but only of blind feeling, dumbly stirring passion that his own dull days had never opened to him. He continued his visits to Ashoka’s house, and lengthened them, spending long hours on the plank bed smoking a drowsily gurgling hookah, and watching the two girls as they went about their housework, cooking rice for him, or for themselves, or polishing with sand the brass water-pots and cups and dishes that were their mother’s pride, till they shone like burnished gold. They never read books, for very few of the women of India ever learn to read. They never sewed, because Bengali women wear only a sari, a single long strip of muslin, draped round them statue-like, with never a stitch in it; they never made baby-clothes, because Indian babies wear clothes; yet they had many gentle household duties, the watching of which soothed Gunga Ram’s burning thoughts, and he never wearied of their pretty, un-bridled chatter, which dealt so frankly, so knowingly with a whole world of things and persons that, for more cloistered women, were an undreamed, undiscovered world.

Ashoka had two misgivings: the first, merely practical, that Gunga Ram, by his prolonged visits, kept other friends away; then a deeper fear, when she caught the flash in Gunga Ram’s eyes, the scowl of his black, clear-drawn brows, if the girls in their chatter spoke of other friends, or other expectations. So dark, indeed, was the face of Gunga Ram, so full of menace, on such an occasion, that Ashoka went so far as to warn her wondering daughters that they had best not speak of other friends when Gunga Ram was there.

They agreed, for they were obedient daughters; but doubtingly, for to their thought the whole of their life was open as the great Padishah road that led away to the dim northland; so, dutifully regardful of the least wish of their kind, clever mother, they managed, though with difficulty and constraint, not to speak of what so greatly interested them and occupied their thoughts.

So there began for the household of Ashoka a time of constraint, of veiled ways of silences; while Gunga Ram spent long hours there, smoking many hookahs; sometimes waking into thoughtful communicativeness, telling the girls and their mother wonderful stories from the age-old Puranas, or from the tale divine of Rama, whose name he bore, and lovely Sita, and that fair Shakuntala to whom the king’s son pledged his troth with a ring. He talked for both the girls, but his eyes were ever fixed on Sundaree, those dark eyes with their hidden fires.

He had scholarly learning, and imagination, and Brahminic fire, had Gunga Ram; and once the stream of his talk began to flow, grew inspiring and enthralling in his eloquence, so that Kusuma listened intent, and Sundaree hung on his words with wide eyes entranced, drinking in the marvelous old stories, and more and more believing that there was never such a man of men as Gunga Ram, the zemindar of Belgaon village.

Then, again, Gunga Ram was moody, absorbed, silent, menacing, when the pent-up powers within him stormed under the scourge of jealousy. For jealous he was; Ashoka, skilled in the ways and thoughts of men, could no longer conceal it from herself; and she saw, with a heart her foreboding future evil, that daughters were awaking to the truth too—Kusuma, as more detached, first divining it, while Sundaree, in the midst of her great dream, was beginning to feel it too; they were awaking astounded, for exclusive possession had so little part in their thoughts that jealousy was almost incomprehensible to them. Woman-like, they bent before the storm, fearful of the threatened anger, and, bending, dissembled, concealing from Gunga Ram the coming and going their friends.

Then came a time of sunshine for Gunga Ram. Thinking that he was their sole guest, only lord of the heart of Sundaree, his jealousy lulled itself to sleep, and all that was in him, companionable, imaginative, passionate, all that the dull, subdued, persons of his life had never evoked, began to pour forth in a golden atmosphere enwrapping Ashoka’s household, circling about Kusuma, and winding like an aureole around Sundaree’s lovely head. So he found joy and delight in the house of Ashoka, great joy in friendliness of Kusuma, greater joy in the rapt devotion of Sundaree.

He talked to them, as never hitherto, lavishing the treasure of knowledge and memory and fantasy, old tales and divine speculations from his venerable palm-leaf scriptures, or new dreams of the modern world, whose tumultuous echoes reached, though hushed into half-silence, even to the remote village of Belgaon, amid the rice fields along the Bhagirathi.

Those were magical days, wherein he felt himself thrice a man; all the hidden fire in his heart blazed up, all the hidden flowers in his thought bore their fruit, so that he spent fewer and fewer hours in the big house of brick, and lingered ever longer in the clay hut thatched with reeds in the north street the village of Belgaon.

Little Kusuma, and Sundaree still more, caught with the reflective power of women, something of his Brahminic fire, and Sundaree shone back to him transformed, full of the play of fancy and charm, discovering new and subtle caresses, enthralling him with fresh-born vivacities and graces. Happy days, these, for Gunga Ram.

Meanwhile the daily life of the household Ashoka went on, surreptitiously, well hidden from Gunga Ram, whose comings and goings were watched and heralded; so that at his coming, all things bore a fair, presentable face, and his conviction that he was the one guest there was confirmed.

For him, for them, came the day of inevitable doom. There descended upon the village two burly Afghans with peaked turbans, bearing huge packs of up-country webs and gauds; pebble brooches from the Himalayan watercourses, fine muslins decked with beetle-wings like gilded emeralds, Delhi satins enameled with arabesques of bright floss silks; many things lovely to the eye and the heart.

They were big rough men, these Afghans, crafty and cruel, as says the proverb, are all Afghans, and their very presence was, in a sort, a reign of terror among the timid Bengalis. The big men towered over them like kings, browbeating and threatening; making their own prices with the stall-keepers in the bazaar and among the women of the north street of the village, where Ashoka dwelt with her daughters.

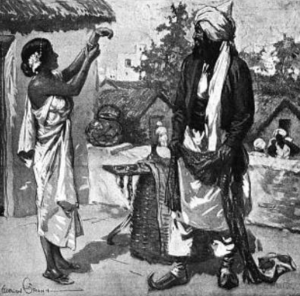

“He watched Sundaree, who was fitting glass bangles on her pretty arm.”[2]

As Fate would have it, weaving the immemorial web, one of the huge Afghans, by name Abdur Rahim, Slave of the Compassionate One, found his way to the mud platform whereon was set Ashoka’s house, swung the heavy pack from his shoulder, and began to bully Ashoka and her daughters into purchasing his wares. But his tongue grew silent and his eyes gleamed with baleful fire as he watched Sundaree, who was fitting glass bangles on her pretty arms.

He declared himself a guest of Ashoka’s house. There was no gainsaying the towering impetuousness of the man. And he snorted with wrath when Ashoka, very diffidently, and timidly, began to speak of the Brahmin zemindar, and of the habit he had formed of coming thither.

Abdur Rahim was a Muslim, and cared not a whit for Brahminhood, with its long trail of idolatrous divinity; he was an Afghan, and cared nothing for the wishes or threats of a Bengali, had a Bengali ever dared to threaten him; he was a wild mountaineer from beyond the Safed Koh, and mocked at all landowners, who were in his thought, but convenient storehouses to plunder. Abdur Rahim was a man, and a passionate one, and recognized no rights in any man, when he had set his heart upon a woman. Therefore, as a Muslim, an Afghan, a mountaineer, and a man, he swore big-mouthed oaths that he would cut the throat of the Brahmin zemindar, or of any Bengali rascal who dared to look askance at him; and the big man’s cruel eyes showed him in dead earnest.

With the imperative desire to hush his terrible and scorching words, they let him in. Leaving his pack conspicuous on the clay platform, and throwing on the clean-swept floor a sharp Afghan dagger, big as a short sword, he established himself lazily on the plank cot, and presently, despite the stern injunction of the Prophet, was drinking himself drunk with the rice liquor of the country, which Ashoka had brought, bending before his stormy, oath-laden command.

Within an hour, toward the mid-quiet of the afternoon, he was lying there, a drunken swine of a man, sleeping heavily and stertorously snoring, while his pack lay, in insolent carelessness, on the mud platform in full view of the street.

Gunga Ram, coming toward the hut, as was his custom at that hour, his head and heart full of sunny dreams stopped some distance up the and stared at the up-country pack, shining there many-colored in the sunlight; at first, not taking the meaning of a thing nevertheless so plain.

Then, his suspicion and jealousy suddenly flaming up, filling his ears with thunderings and his eyes flashes of fire, he came on furiously raging, ascended the two steps of the clay platform, and stood there, straining his eyes into the half-darkness of the interior.

The big, murderous Kabuli knife, heavy as a sword, keen as a lancet, glistening there on the clay floor, first caught his eyes; then through the dusk the Afghan’s body, sprawling there along the bare plank cot, with huge hairy arms and legs extended, his turban careless of religious prohibition, fallen in disarray on the floor, his big throat throbbing swollen arteries, as he snored and spluttered in sleep.

Then slowly Gunga Ram became aware that were watching him, eyes full of fear, dilated in darkness; and turning in obedience to the power of the glowing eyes, he saw Kusuma and Sundaree crouching against the mat wall, watching in mute anguish.

No need for questions. The pack, and the dagger, and the big brute asleep, told their tale plainly. The eyes, wide with terror, that were fixed on him, gleaming in the darkness like the fear-struck eyes of birds, told the tale again.

Gunga Ram saw his whole world toppling about in ruins, his golden dream-towers crumbling in disgraceful dust. The furious fires of passion, at white heat now, turned in upon him, filling heart with raging demons that shrieked horribly revenge. And those eyes watched him from the darkness, shining like the fear-struck eyes of birds, as the two crouched against the leaf-mat wall.

Whether the drawing power of their eyes the direction of his revenge, or the deep, hereditary dread of the hill-giants that dwells in every Bengali heart, cannot be known; but certain it is that, picking up the Kabul knife from where it lay, he stopped haltingly across the clay floor to where the two crouching. Sheer terror held them silent, motionless; and, while the huge Afghan brute snored and spluttered in his drunken slumber, the brass jar of rice-liquor on the floor beside him, Gunga Ram, groaning aloud in his anguish, hacked the lives out of Kusuma and Sundaree. In the subjection that fills the hearts of all the women of India, they made no motion resistance; presently they lay prone on the floor, writhing a little, as Death touched them.

Gunga Ram stood there in the dusk, the Kabul knife still in his hand, trembling and groaning in his intolerable pain.

Ashoka, when he stooped down toward the knife, had fled shrieking along the street, and almost immediately a crowd gathered, her women friends, the idlers in their houses, the stall-keepers from the bazaar; they peered, whispering, through the shadows at Gunga Ram, now kneeling beside the two little bodies, and at the huge Afghans, snoring and spluttering on the cot.

Even then, after the Bengali police-sergeant and his two men came, in their ill-fitting uniforms, from the village thana, and pushed their way through the whisperers. Gunga Ram might have gone free, and the whole affair might have been hushed up; for from so great a man there was hope of much gain, and a Brahmin is still sacrosanct to many who would have been willing to hide his fall.

But Gunga Ram knelt there groaning, like a man who had lost clear sense of things, and now and then he touched the two little bodies, softly fingering them, questioningly, as though he looked for them to wake and talk to him.

It was thus the sergeant of police took him kneeling there, making no least effort to escape, his whole mind and heart overwhelmed by the great calamity. Ashoka had come back now, and in an awed silence fixed her eyes on him, full of bewildered dismay. Presently she would awake again to the misery and terror of her loss and begin to rend the air with shrieks.

Gunga Ram rose and departed with the policemen, not shackled, for that was clearly unnecessary, and would have been a needless shame to put upon a Brahmin. His eyes were full of quiet anguish, not abashed, for the Deva in him, the kindred of the gods, was still a god in the hell of his heart; not fearful, for death, to him, as to so many Orientals had no terrors at all, and was but an incident in the ceaseless chain of births; dwelling on his own fate, indeed, not at all, but full of irremediable sorrow for Sundaree, the Lovely, and for her little sister Kusuma, the Blossom.[3]

← Table Of Contents →

SOURCES:

[1] Johnston writes: “By May 20 we had the ‘little rains,’ drenching us for a few days only, and searching out all the vulnerable points in our cement roofs.” [Johnston, Charles. “A Perspective On India.” The Atlantic Monthly. Vol. 138, No. 6. (December 1926): 848-856.]

[2] Johnston, Charles. “The Tale Of Gunga Ram.” Harper’s Weekly. Vol. LVI, No. 2882. (March 16, 1912):16-17.

[3] Ibid.