I don’t want antisemitism to be misunderstood. I don’t want Jews, Zionism and Israel to be conflated. I don’t want to be perceived as supporting an oppressive and undemocratic State, just because I’m Jewish. I don’t want to be associated with a one dimensional interpretation of Zionism which denies another people their history and identity. I don’t want the definition of racism against me to mean another people cannot protest the racism against them.

But if I support the IHRA definition of antisemitism, all of this is exactly what I’m signing up to. That’s why we need to decolonise our understanding of antisemitism as a matter of urgency. And that means ditching the IHRA.

Here, for those not already familiar with IHRA, is the definition itself and then the two illustrations (drawn from eleven examples in the document) which have succeeded in generating such divisiveness and antagonism:

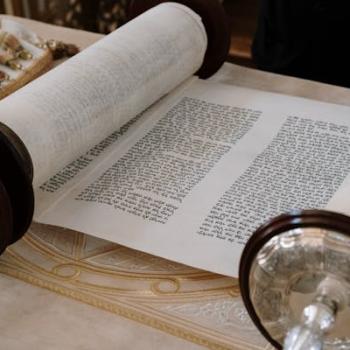

“Antisemitism is a certain perception of Jews, which may be expressed as hatred toward Jews. Rhetorical and physical manifestations of antisemitism are directed toward Jewish or non-Jewish individuals and/or their property, toward Jewish community institutions and religious facilities.”

-

Denying the Jewish people their right to self-determination, e.g., by claiming that the existence of a State of Israel is a racist endeavour.

-

Applying double standards by requiring of it a behaviour not expected or demanded of any other democratic nation.

If the IHRA illustrations are now considered so central to defining antisemitism, then by implication they must also define what it is to be Jewish.

By that reckoning, to be Jewish is to deny the possibility that Zionism has played out in racist ways, despite the overwhelming evidence to the contrary. And to be Jewish is to believe that the State of Israel is a democratic nation like any other, despite Israel’s own constitutional laws defining it as the nation state of the Jewish people rather than the state of all its citizens. And that’s before we get to the not insignificant fact of an occupation of Palestinian land which has lasted for most of the State’s entire history. So to be Jewish, according to the IHRA, is to deny the truth, ignore reality, and defend the indefensible. Thanks, but no thanks. I don’t need or want this colonised version of Jewish identity to define me or what it is to be Jewish. And nor should anyone else.

Mighty failure

I’ve reluctantly come to the conclusion that those who have been promoting the IHRA don’t really care about Jews, Judaism or our current and future relationship with other ethnic/religious minority groups, in particular the Palestinian people. If I’m right, this is a state of affairs which suggests a mighty failure at the heart of Jewish communal leadership.

Judging by their unhesitating support for IHRA, the Board of Deputies, the Union of Jewish Students, the Chief Rabbi, and every other formal Jewish institution in the UK, appear to know little about how you create broad alliances to tackle the power structures that generate and sustain racism around the world (including antisemitism). Not only that, they seem to understand little about the journey needed to reach a genuine, just and lasting peace for all the people of Israel/Palestine.

Weak and clumsy

It’s troubling that the leadership of the Jewish community in the UK believe that such a badly written and morally problematic document will help tackle antisemitism, or build alliances with non-Jews, especially on university campuses.

The actual 40-word definition is the weakest and most clumsily phrased definition of antisemitism I’ve ever read. Antisemitism does not start with “hatred” as the IHRA says, it starts with petty prejudice and discrimination, it starts with winks, slurs and innuendos. This definition sets the mark far along the spectrum of antisemitism and fails to understand how it’s not just irrational “hatred” but religion, economics, and political power that have shaped hostility towards Jews. And was it really so hard to find a halfway decent copywriter to wordsmith this definition into plain English?

No red faces

Over the last four years, there’s been a steady build-up of concern and opposition to the IHRA from around the world, including from notable Jewish experts on antisemitism such as Kenneth Stern and David Feldman who can hardly be described as ‘lefty Jewish anti-Zionists’. Yet, the Board of Deputies shows not the slightest discomfort or unease about such criticism.

There are legal concerns, free speech concerns, and, quite rightly, huge concern about the impact it has on the expression of Palestinian identity and the ability to campaign for Palestinian equal rights. By now, there really ought to have been at least some reddening of faces, or perhaps a nagging feeling of embarrassment from those who have been championing this document and actively foisting it on just about everybody else.

If something you think is so perfect and so needed gets this amount of global kick-back, a reasonable person might pause for thought and reflection and take a moment to re-evaluate their strategy. But there’s no sign of that here in the UK. Instead, IHRA continues to be promoted as the only satisfactory way for public institutions to express their commitment to tackling antisemitism and their solidarity with the Jewish community. Anything less is regarded as suspect at best. It’s not hard to see why many of the organisations being lobbied just say, “fine, we’ve adopted it”. Few have the time, energy or political capital to expend on an argument with the Board of Deputies. A quiet life is preferable.

Identity politics

Beyond IHRA being, “what the Jewish community wants”, I’m yet to hear an argument made for it which explains exactly why it’s so good (and better than anything else) despite the fury it’s created and the shoddy formulation of the actual definition.

This standard line of justification was used in January this year by the Union of Jewish Students (UJS) as it stepped up its defence of the document under mounting criticism of its adoption and usage from around the world. In a letter to the Guardian the UJS President, along with the leaders of dozens of Jewish campus societies around the country, chose to use a dumbed-down version of identity politics to make their case:

“It is time for a discussion of the IHRA definition and its adoption by British universities to reflect the lived realities of Jewish students. Retired judges, activists based in the Middle East and far-left non-Jewish academics are not on the frontline enduring antisemitism on campus – we are.”

The lack of self-awareness and disrespect on show here is quite staggering. But left out of this list of people whose opinions don’t count to UJS are Palestinian students on UK campuses. They don’t even merit a mention. Their “lived realities” are erased entirely in this letter of Jewish self-righteousness, just as the IHRA illustrations erase Palestinian history. This does the interests of the 8,500 Jewish members of UJS absolutely no service whatsoever.

In the last few days, Palestinian students on my own campus at Lancaster University in the north of England have been suffering appalling racist and misogynistic insults made online, (along with the usual casual allegations of antisemitism thrown in), because they dared to speak out against IHRA. The University authorities are investigating the incident. So far no action has been taken. It’s just one more example of IHRA doing much harm and little good.

This is where you end up when identity-based politics goes wrong. Discrimination against one group cannot be articulated in a way that relies on discriminating against another group. If this is where you end up, you’ve taken a wrong turning and got badly lost.

Decolonising antisemitism

There’s no point in a definition of antisemitism which embeds within it another form of racism. So we urgently need to de-politicise and decolonise our formulation of anti-Jewish racism. To achieve that we need to decolonise mainstream modern Jewish identity too. Alana Lentin, an antiracist race critical scholar, identifies and explores the need to ‘decolonise antisemitism’ in her 2020 book ‘Why Race Still Matters’ Those who study, campaign against and comment on antisemitism will benefit from Lentin’s analysis, as I have.

Zionism has been, and still is, a Jewish liberation movement born out of a desire to escape antisemitism. It believes that national self-determination in the form of a Jewish state is the only way to achieve this. However, it’s also been, and still is, a project of Settler Colonialism which has led directly to the dispossession and continued oppression of the Palestinian people. Both descriptions are true. One does not cancel out the other. They co-exist simultaneously.

As I’ve written before, the concept and experience of Zionism does not belong exclusively to the Jewish people, let alone a Jewish leadership elite in the UK with minimal accountability.

The situation in Israel/Palestine creates a profound ethical problem for anyone who cares about justice, fairness and equality; anyone who cares about Jewish history; anyone who cares about the Jewish ethical tradition. That’s what makes Israel/Palestine the greatest challenge facing Jews, and indeed Judaism itself, in the 21st century.

Simply by acknowledging the challenge and what has caused it, we begin the work of decolonising Jewish identity and can begin to formulate a progressive understanding of antisemitism.

Tackling antisemitism without prejudice

To be Jewish in 2021 is to live in a world of contradictions and ambivalence. It’s a time in which on-going Jewish vulnerability exists side-by-side with Jewish empowerment and the Israeli oppression of Palestinians. It’s possible to be a victim of racism in one space and a generator of it in another. The word ‘complicated’ doesn’t begin to capture the intersecting dynamics of contemporary Jewish identity. And this can confuse Jews themselves as much as anyone else.

There are some on the left who choose to fight racism against Palestinians by taking the low road to antisemitism. Such attitudes are badly misguided and do harm to both Jews and to the cause of Palestinian solidarity. Meanwhile, there are those on the right, or those who call themselves liberals, who think it’s okay to fight antisemitism by promoting discourses that encourage islamophobia and certainly anti-Palestinianism. This is where promoting and defending the IHRA takes you.

The bottom line is this: you don’t fight racism with racism. You don’t fight hate with hate, no matter how unfair or unpleasant your opponents might be. Other, and far better, tactics are available.

So, if you want a constructive and unifying debate about antisemitism; if you want to decolonise Jewish identity; and if you want to chart a route to a reconciled Israel/Palestine, then for the love of God, ditch the IHRA.

Note: I’m grateful to Alana Lentin for identiying and exploring the concept of ‘decolonising antisemitism’ in her book ‘Why Race Still Matters’. If you want to read more about how some key Jewish thinkers have understood colonialism and Jewish identity more broadly I’d recommend. ‘Decolonial Judaism’ by Santiago Slabodsky. For a detailed account of how Settler Colonialism has played out in Israel/Palestine, see Jeff Halper’s new book ‘Decolonizing Israel, Liberating Palestine: Zionism, Settler Colonialism, and the Case for One Democratic State’.