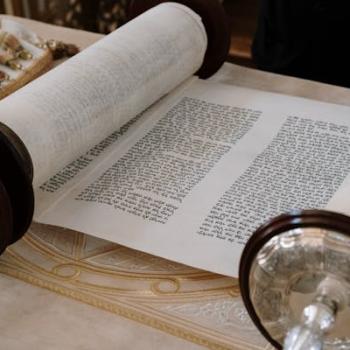

My last post discussed the Jewish belief in an Oral Law that accompanies the written text of the Bible. I tried to show that in numerous instances, biblical laws are either too vague and unclear or too unspecific in their precise definition/application to be understood. Therefore, if we believe that God wrote these laws and made it possible to follow them, we must also believe that He gave its first readers the non written explanations they needed to make sense of the text.

All of that is true, but it raises a further troubling question: namely, why would God give the Jews BOTH a written text AND oral explanations? Why couldn’t He have chosen to do one of those things and stick to it? So He could have either made the Bible a lot longer and more elaborate, precisely specifying all the details that are left out. Or He could have forgone the written text and just taught the Jews the entire Torah by heart, like the West African griots who memorize and pass on the myths and history of their ancient peoples.

In any case, why does Judaism have this bizarre two tiered system? It sure would be simpler if we could just say ‘sola scriptura’ (only scripture!) like the Protestants do and insist that the written text is all you need. We believe that’s incorrect, but why did God set the system up our way to begin with?

Rabbi Sampson Raphael Hirsch, a prominent 19th century German rabbi, wrote about this idea in his Bible commentary on the verse Exodus 21:2:

“The Written Torah is to the Oral Torah just as short notes are on a full and extensive lecture on any scientific subject. For the student who has heard the whole lecture, short notes are quite sufficient to bring back afresh to his mind at any time the whole subject of the lecture. For him, a word, an added mark of interrogation or exclamation, a dot, the underlining of a word, etc. is often quite sufficient to recall to his mind a whole series of thoughts.

“For those who had not heard the lecture from the Master, such notes would be completely useless. If they were to try to reconstruct the scientific contents of the lecture literally from such notes they would of necessity make many errors. Words and marks which serve those scholars who had heard the lecture as instructive guiding stars to the wisdom that had been taught and learnt, stare at the uninitiated as unmeaning sphinxes. The wisdom and truths, which the initiated reproduce from them (but do not produce out of them) are sneered at by the uninitiated, as being merely a clever or witty play of words and empty dreams without any real foundation.”

In what I think is a very helpful analogy, Rabbi Hirsch compares the Biblical text vs. its elaborate oral interpretations to shorthand notes on a lecture vs. the lecture itself. The written text of the Bible merely represents the notes of the verbal “lecture” that God and Moses gave the Jews on Mount Sinai and for the next 40 years as they wandered the desert!

If the oral law is the actual lecture, then why was the Bible written down at all? Rabbi Hirsch seems to answer that a written text is necessary to provide all readers on all levels with the basics. To master the entire oral law takes many years. To read the Five Books of Moses takes six months, if you read a chapter a day. By analogy, it would be nice if everyone could read Shakespeare. But for those who can’t, it’s certainly better to read the Cliffnotes version than to read nothing at all!

So the basics are written down for everyone to read, review, and remember them. Beyond that, in terms of a comprehensive Law that will cover all questions at all times, that cannot be written down. The Torah is infinite, just like its Author. Also, there’s a nice side benefit of an oral tradition: it ensures that children will always learn first from their parents and sages, rather than running straight to Google.

That system makes sense to me, at the very least. Hope you found it helpful too.