Sure, Noah was a good guy. The Bible spells that out pretty clearly:

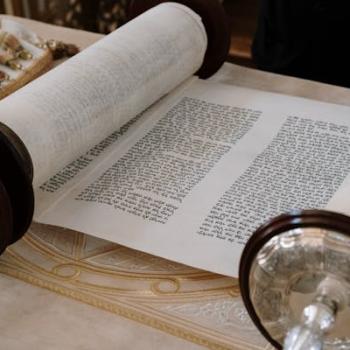

“Noah was a righteous man, blameless among the people of his time, and he walked faithfully with God.”

(Genesis 6:9)

Or does it?

The Talmud (Sanhedrin 108a) quotes an opinion that reads this verse as a sort of backhanded compliment to Noah:

“In comparison with his generation he was righteous, but if he had been in Abraham’s generation, he would not have been considered of any importance.”

Sure, he was good relative to his contemporaries. But that’s only because everyone else was so bad!

Where did the rabbis come up with this insight into Noah’s personality? What clues about Noah’s character led them to read this ostensibly positive Biblical verse in such a derogatory fashion?

Part of the reason is because they knew how the story ends. Noah was handpicked by God to survive the flood and begin the human race again, this time on the right foot. Instead, soon after the flood, Noah plants a vineyard, gets drunk, and becomes naked and humiliated in his tent (see Genesis 9:20-22).

But that alone isn’t enough. After all, maybe Noah started off good and just ended up bad. Maybe he was suffering from some form of PTSD after surviving a catastrophic flood! So we have to keep looking.

A more profound clue into Noah’s character can be found right in the beginning of his story, when God first tells Noah about the impending flood (“…I will wipe from the face of the earth every living creature I have made” (Gen 7:4)) and commands him to save some animals.

What is Noah’s response to hearing this terrible news? The next verse says it all:

“And Noah did all that the Lord commanded him.”

(Gen. 7:5)

This reaction doesn’t sound so bad. Isn’t obedience good? Well, sometimes it is.

But here, it’s reasonable to assume that Noah’s passive obedience wasn’t the right move. Because God of Genesis wants partners, and not merely followers. How do I know that?

A few chapters after Noah’s story, God chooses Abraham as the forefather of His chosen nation. And soon after that, we see Abraham do the exact opposite of what Noah does.

In Genesis 18, God decides to destroy the cities of Sodom and Gomorrah, on account of their wickedness. Sound familiar? It’s basically a microcosmic rerun of the flood story all over again, except that now we have Abraham standing in Noah’s place.

Upon hearing the news of Sodom and Gomorrah’s destruction, Abraham doesn’t just sit back and let it happen. Instead, he approaches God and immediately goes on the attack:

“Will you sweep away the righteous with the wicked Far be it from you to do such a thing—to kill the righteous with the wicked, treating the righteous and the wicked alike. Far be it from you! Will not the Judge of all the earth do right?”

(Genesis 18:23,25)

Abraham was chosen, while Noah was not. Abraham challenged God based on his own personal sense of justice and morality, while Noah obeyed the Lord and watched Him destroy the world.

I didn’t invent this connection; the Zohar, the most important work of medieval Jewish mysticism, noticed it first:

“Rabbi Yochanan said, “Come and see the difference between the righteous among the Jews after Noah, and Noah. Noah did not defend his generation, nor did he pray for them, as Abraham did. When God told Abraham that [he would destroy] Sodom and Gomorrah … immediately Abraham began to pray in front of God until he asked of God if ten good people were found, would God forgive the entire city because of them.”

(Zohar Hashmatot Bereishit 254b)

This idea connects nicely to my recent post about Jewish chosenness. Being chosen doesn’t mean being apart from the world and obeying God in your own personal island without caring for others.

Rather, as Abraham shows us, to be chosen means to take on the mantle of defending and praying for all people, even amoral pagans, advocating on their behalf before God and educating on God’s behalf to whoever will listen.