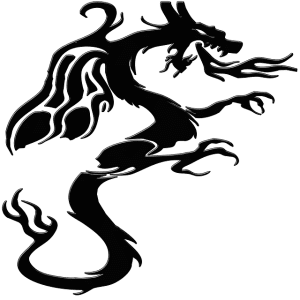

Leviathan is an extraordinary creature that we read about in the Book of Job 41. Is this a fire-breathing dragon, a mythological monster, a poetic description of a natural creature, or something else? What do biblical texts and other ancient traditions say about this beast?

Job and Leviathan

Towards the end of the book of Job, God appears to Job and relays a set of questions to him that exemplify the mysteries of God’s creation and his extraordinary power over it.

God speaks about Leviathan at length, which suggests that this beast to be the mightiest of earthly creatures. The fearsome beast breathes out fire and smoke (Job 41:18–21), has impressive teeth and scales and, among other things, it can easily break iron and bronze. Human weapons are useless against it (41:7–8, 14–17, 25–29). No human is able to capture or tame this wild monster.

In relation to Job’s complaint over his suffering, as John Day affirms, “The point of God’s argument seems to be that since Job cannot overcome Leviathan, how much less can he hope to overcome in argument the God who defeated him. Accordingly, Job repents in dust and ashes (Job 42:1–6)” (“Leviathan,” Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary, 4:296).

Interpreting Leviathan

A straight-forward reading of this text might suggest Leviathan is a gigantic fire-breathing dragon resembling those of ancient legends and folklore. Indeed, the Septuagint version of Job replaces “Leviathan” with “dragon” in the Greek (drakōn: LXX Job 40:20 [English tr. 41:1]; Isa 27:1).

Leviathan comes from the Hebrew consonants lwytn, which may be derived from the Aramaic lwy meaning “to twist” or “coil” as though a serpent. Or it may originate from the Ugaritic ltn that stands for the Lotan (or Litanu) monster. In ancient Ugaritic mythology, we have the god Baal and his consort Anat battling against Yamm (the sea god), choking out Tannin (or Tunnam, a dragon), and smiting Lotan, a seven-headed twisted monster.*

These mythological gods seem to creep over into poetic and prophetic biblical texts.

Leviathan in Psalms and Isaiah

In Psalm 74, the psalmist calls on God to be a defender against his enemies. In 74:13–14, the psalmist recalls God’s great works, such as dividing the sea, breaking the heads of sea monsters, and crushing the heads of Leviathan (note the plural). God gives this creature as food for people and for desert inhabitants or creatures. The Psalm shows Israel’s God to be supreme over creation, chaos monsters, and foreign powers.

We find a similar portrait in the prophecy of Isaiah 27:1. Here the Lord will punish the twisting serpent, Leviathan, and kill the dragon (tannin) in the sea. Some may compare with this passage Satan as the seven-headed dragon and serpent who is cast down in Revelation 12. In this New Testament passage, however, Satan is not named Leviathan.

These texts seem to suggest a different type of beast than the Leviathan we read about in Job. The creature in Job apparently has only one head, not seven. And even though this beast is ferocious, we sense that it is simply one of God’s many splendid creatures. Job’s Leviathan does not appear to be an evil being, and it is not a foreign deity from an enemy nation.

The Leviathan in Job resembles what we find in Psalm 104:26. This song praises the Lord’s greatness and works creation, including Leviathan, which he formed to play in the sea. Leviathan here is sort of like God’s “bathtub toy” that God delights in and shows himself to be far more powerful than this massive beast he created. **

A Natural Beast?

A more rational interpretation of Job 41 became popular in the modern era. Post-enlightenment thinkers considered sea serpents and fire-breathing dragons as fables; for them, such stories could not be taken seriously (see the reception history of Leviathan in Mark R. Sneed, Taming the Beast: A Reception History of Behemoth and Leviathan; Berlin: De Gruyter, 2021).***

Hence, certain interpreters these days prefer to identify Leviathan as a crocodile or whale. Leviathan appears in the same context in Job as Behemoth, another massive creature (see Job 40:15–24). It is not much of a stretch to believe that Behemoth is a natural beast, whether a mammoth or hippopotamus. It is then surmised that Leviathan must also be a natural animal, if interpreters allow for some poetic hyperbole.

A Dinosaur?

Other interpreters suggest these beasts are dinosaurs. But to do so, it seems that they must reject the claims of paleontologists who teach that dinosaurs have been extinct for millions of years. Leviathan on this reading becomes a “mighty dinosaur” (Walter Kaiser, et al, The Hard Sayings of the Bible, 1996:262).

Personally, I don’t believe that scenes resembling Jurassic Park were once the reality. But I do wonder how ancient people might have reacted if chancing upon dinosaur fossils. What would they think about these remains and what type of stories might they invent about the existence of such creatures?

All the same, perhaps some interpretations of Leviathan need revision. The Book of Job is wisdom literature with poetic and figurative language. It does not need to be read as an actual history, let alone literally, even if Job happens to be an actual person (cp. Ezekiel 14:14). The point of the discourse is not that Job and his friends historically delivered all the verbatim words of the speeches that we find in this writing. Rather, the book seems to be written as a type of parable about why suffering happens to people who don’t seem to deserve it. As such, our attempts to rationalize, naturalize, or historicize Leviathan might be barking up the wrong branch.

Sightings and stories about sea monsters and giant beasts would have been real enough for the original audiences of this book. And so maybe we do not need to probe any further than this, at least with regard to the Leviathan in Job.

Food for the Faithful? Leviathan and Behemoth in Early Jewish Traditions

The Leviathan also appears in later Jewish traditions comparable with the time of the writing of the New Testament and beyond. In these writings, a different emphasis is given to the beast.

1 Enoch 60

In Enoch’s Book of Parables, we learn that Leviathan is female and Behemoth a male. They are parted with the former being assigned to the abyss of the sea and the latter sent to the wilderness, east of Eden. The two monsters wait for the great day of the Lord in which they will become food (1 Enoch 60:7–9, 24).

The notion of others eating Leviathan echoes Psalm 74, though now such a feast is set for the future. We seem to have in the Parables of Enoch and other apocalyptic texts a wicked type of Leviathan, such as we find in Isaiah 27 rather than the morally-neutral brute in Job.

4 Ezra [2 Esdras] 6:49–52

In this text the Lord creates living creatures including Behemoth and Leviathan. Behemoth lives on dry land and Leviathan in the water. We find here a prelude to what will happen to them in the future: “you have kept them to be eaten by whom you wish, and when you wish” (2 Esdras 6:52 NRSV).

2 Baruch 29:3–4

During the apocalyptic time of calamities and revealing of the Messiah, the two monsters, Behemoth and Leviathan, will appear again. God preserves them for that time, and they will become nourishment for the remnant of human survivors.

An example from post-biblical times comes from the Talmud:

Babylonian Talmud, Baba Bathra 5:1 (75a: IV.28)

“Rabbah said R. Yohanan said, ‘The Holy One, blessed be He, is destined to make a banquet for the righteous out of the meat of Leviathan: ‘Companions will make a banquet of it’ (Job 40:30).” (translation from Jacob Neusner, The Babylonian Talmud: A Translation and Commentary, Hendrickson, 2011: 23. In the Jerusalem Talmud and Babylonian Talmud see similarly, e.g., y. Megillah 74; y. Sanhedrin 10:29C; b. Moed Qat. 25B).

Conclusion

Unlike Job’s Leviathan, in the age to come, this monster becomes the main dish on a dinner menu. If these traditions are applied to New Testament texts, they would put an interesting spin on the Messianic banquet (Matthew 8:11; Revelation 19:9). Vegans might have a problem with this, though we should remember that apocalyptic literature is highly symbolic. I suspect that the consumption of Leviathan may be pointing to the end of all enemies and powers against God.

For foodies like me, I wouldn’t mind a little bit of literalism at the upcoming banquet! I keeping reminding myself that even after Jesus rose from the dead, he eats fish with his disciples (Luke 24:36–43; John 21:4–14).

Bon Appetit!

Notes

* See E. Lipinski, Theological Dictionary of the Old Testament, 7:504–509. Also, F. J. Mabie, “Chaos and Death,” in Dictionary of the Old Testament: Wisdom, Poetry, and Writings (IVP, 2008), 41–54.

** The words in quote I adopt from Kathryn Schifferdecker, “Creation Theology,” in Dictionary of the Old Testament: Wisdom, Poetry, and Writings, p. 64 (63–71).

*** See also the helpful review and critique of Sneed’s book by Jason Kalman in Review of Biblical Literature 3/2023.