By Rabbi Jim Morgan RS ‘08

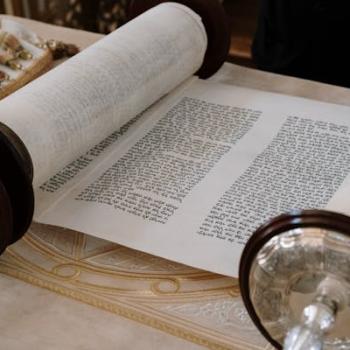

Parashat Chayei Sarah (Genesis 23:1-25:18)

At Centre Communities of Brookline, an independent housing facility in Massachusetts where I serve as Community Rabbi and Chaplain, I have the privilege of working with a surprising number of very old people. By “very old,” I mean folks in their nineties or older, including one person who recently turned 106. Among the questions that come up in my conversations with these residents is why they are still alive: what is there for them to do now that, in many cases, their hearing is faint, their vision dimmed, their mobility more limited than it was even a few years ago?

The answers, as you might imagine, vary considerably. One such resident, Ammi Kohn, recently published his memoir, Unfinished: My View from the Ninth Decade, and was featured in Oldster Magazine. Others, with less energy and more disability, confess to feeling adrift, overwhelmed by the relentless loss of loved ones and friends and unable to seriously contemplate an extended project like a memoir or even regular attendance at social opportunities or learning programs. The recent events in Israel and Gaza have added extra bitterness for so many people of this generation, who in their conversations with me, recall all too well the antisemitic sermons of Father Coughlin; recount the tormenting drip of information about the Shoah that appeared in the Yiddish press that was generally unknown to their English-speaking neighbors; and remember their parents’ stories of Eastern European pogroms, inherited trauma reawakened by the atrocities of Hamas in Southern Israel.

In this context—of trauma and loss, the death of spouses and friends—we come across our patriarch Abraham in Parashat Chayei Sarah, the “Life of Sarah,” which in its familiar paradox opens with the death of Sarah, the life in the title referring to the number of her years: 127 (Gen. 23:1-2). The focus is on Abraham: his mourning, his tears, and his efforts to purchase land for Sarah’s burial; such are the tasks that befall a bereaved spouse. By the end of this process, the Torah reports, again in apparent paradox:

וְאַבְרָהָם זָקֵן בָּא בַּיָּמִים וַיהֹוָה בֵּרַךְ אֶת־אַבְרָהָם בַּכֹּל׃

Abraham was now old, advanced in years, and יהוה had blessed Abraham in all things. (Gen. 24:1).

Ramban, following Rabbi Yochanan in Genesis Rabbah 48:16, asks why the Torah reiterates that Abraham was old, now that he is 137 years old. Wasn’t he already old nearly 40 years before, when he and Sarah laughed with surprise that a 100-year-old man would become a father again with a 90-year-old wife (Gen. 17:15-17; 18:11-12)? Indeed it says:

…וְאַבְרָהָם וְשָׂרָה זְקֵנִים בָּאִים בַּיָּמִים

Now Abraham and Sarah were old, advanced in years… (Gen. 18:11).

The midrash suggests that it is because, even though the theophany at the Terebinths of Mamre rejuvenated Abraham, he had in the subsequent years become old again. But Ramban prefers the midrash’s second suggestion and devises a grammatical explanation to support it:

In Genesis Rabbah. the Rabbis (Rabbi Ami) said: “Here (in 18:11) it was old age combined with vitality; further on (in 24:1) it was old age without vitality.” By this the Rabbis wanted to explain that ba’im [with the meaning “advanced” in years]—means the beginning of the days of old age, as the word ba’im indicates the present tense…. But here [24:1] it says that he was very old for already he was ba bayamim [literally: “he had advanced in years”—past tense]. (Ramban on Genesis, 24:1)

Given that Abraham has buried his wife and endured the terrible trial of the Akedah (which the Rabbis suggest was the proximate cause of Sarah’s death), I would propose that verbal tense here is less important than number. Ba’im indicates the plural, Abraham with Sarah, facing the challenges and the absurdity of old age together. Ba, in the singular, means solitary old age, the kind of isolation that feels all too familiar to many older Americans today. This “old age without vitality” is what, in Ramban’s reading, prompts Abraham to send his eldest servant to look for a wife for Isaac: “Abraham saw himself as very old, so old that he would likely not live long enough to see the servant return with a bride for Isaac.”

Yet we also see that Y-H-W-H had blessed Abraham in all things, blessings of wealth and stature, of wisdom and spiritual purpose. In sending his servant to find a wife for Isaac, Abraham takes action to fulfill the task of his old age: ensuring that his line of offspring with Sarah will not end with his rather passive son. And indeed, when the servant has succeeded in bringing Rebecca back to the land of Canaan, we see that Abraham then continues to live:

וַיֹּסֶף אַבְרָהָם וַיִּקַּח אִשָּׁה וּשְׁמָהּ קְטוּרָה׃

And Abraham took another wife, and her name was Keturah. (Gen. 25:1)

The translation here elides the crucial verb, vayosef [he continued], which captures the reality for many people after losses and transitions of all kinds. For Abraham, this continuation involves finding renewed vitality with a new wife in his old age. His marriage to Keturah—whom the tradition often identifies with Hagar, the mother of Abraham’s first son Ishmael—proceeds without any reference to his advanced age, with no laughter about the impossibility of such an old man siring an entirely new family of six sons (and, perhaps, an unspecified number of daughters). In this case, life just goes on.

I do not mean to suggest that marriage, or romantic partnership in general, is the only way for older people to find vitality in their old age, although it certainly is one way for people to feel rejuvenated. Rather, it is all kinds of vital connections with other people that bring meaning and purpose to our lives throughout the lifespan. And these connections do not need to be extended commitments. Indeed, less than a week after the attacks in Southern Israel, we hosted a group of young adults from Haifa who had arrived in Boston a few days before the war began. Three of them had the opportunity to spend a few minutes with one of our centenarians, a survivor of the Shoah whom I’ll call Sarah, and who is a model for someone facing old age with vitality. Within the short duration of their visit, Sarah had adopted the three as surrogate grandchildren, had hugged them, and had granted them a measure of her grace and resilience in the face of unspeakable loss. And they had given her some of their youthful energy and commitment to the future. May we all experience such blessings as we grow older.

Rabbi Jim Morgan’s primary role is Community Rabbi and Chaplain at Center

Communities of Brookline, a Supportive Housing Community of Hebrew

SeniorLife. In addition, he serves as the Russian-speaking chaplain at Hebrew

Rehabilitation Center in Roslindale. Finally, he is Rabbinic Advisor for the

Worship and Study Minyan at Harvard Hillel in Cambridge, a pluralistic, lay-led

congregation that serves the university and the larger community.