Passover, or Pesach in Hebrew, is celebrated this year from April 22 to April 30. It is one of the most significant and meaningful festivals in Judaism. In this article, we will learn from Naomi Klein, a Jewish environmentalist and writer, on her reflection on Passover and its challenge to Zionism.

To develop this discussion, we shall proceed in three parts. First, we will explore Pesach, its history, rituals, and general meaning for the Jewish people, as well as the significance it has had for other people groups throughout history. Second, we will see how Zionism draws from the Passover story to justify Israel’s occupation of Palestinian land. Third, we will meet Naomi Klein, and think through her recent speech on how Passover actually challenges Zionist interpretations of it.

I. Passover: A Festival Rooted in Scripture

Passover centers on a narrative found in the Hebrew Scriptures, or what Christians know as the Old Testament. The Hebrew Scriptures is referred to as the Tanakh, and is essentially made up of three parts.

The first part is the Torah, or “instruction.” The books of the Torah are known in the Western world as Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy. Scholars will refer to the Torah as the Pentateuch, which is Latin for “five books.”

The second part of the Tanakh is the Nevi’im, which is Hebrew for “the prophets.” Here, we find books which Christians usually categorize as historical books, such as Joshua, Judges, the books of Samuel, and the books of Kings. These are called the “former prophets.” The “latter prophets” include major prophets like Isaiah, and minor prophets like Jonah.

The final part of the Tanakh is the Ketuvim. This section of the Hebrew canon means “the writings.” Here, we find wisdom literature like Ecclesiastes and Proverbs, there’s Ruth, Song of Songs, Ezra-Nehemiah (in Judaism, these two books are one), and others.

The Story of the Exodus

So, what is the Passover story? It is the exodus story! The exodus story is found in the book of Exodus. It describes Israel’s deliverance from Egypt. It is this story that The Prince of Egypt (1998) captured and retold so well. (Though many Christians see The Prince of Egypt as a Christian movie, it was developed with all Abrahamic faiths in mind.)

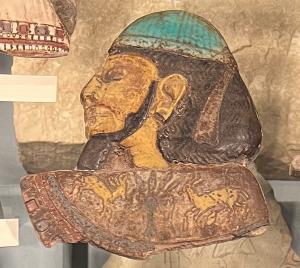

Exodus begins where Genesis leaves off. At the end of Genesis, a man named Joseph becomes the second most powerful man in the world. He becomes Pharaoh’s right hand man. Joseph’s family wins status and protection. But in Exodus, a new Pharaoh ascends to power. This king, we are told, “did not know Joseph” (Ex. 1:8, NRSV).

So the Israelites, who had grown numerous, were seen as a threat. They were thus subjected to slavery in Egypt. Years passed, and God chose a group of siblings, Moses, Aaron, and Miriam, to liberate their people. Moses confronted Pharaoh, and demanded that the king would let God’s people go (7:16).

Because of Pharaoh’s refusals, God plagued Egypt. The twelve plagues included the Nile river turning to blood, swarms of locusts ruining crops, disease, and finally, the death of every firstborn son in Egypt. The death of the firstborn is actually where Passover gets its name. To ensure that an Israelite child would not be killed in the crossfire, God instructed the Israelites to cover their door posts with lamb’s blood. When God saw the blood, He said He would “pass over you, and no plague shall destroy you when I strike the land of Egypt” (Ex. 12:13). At last, Pharaoh let the people go, and God delivered Israel from their oppression.

The Reception History of Passover and the Exodus

In the Hebrew Bible, God tells Israel to celebrate the day of Passover, calling it a “day of remembrance” (Ex. 12:14). Ever since then, the Jewish people celebrate Pesach every year. While the Temple was still standing, Passover was actually a pilgrimage holiday. (Pilgrimages are common in Abrahamic faiths, especially in Catholicism and Islam).

However, the Temple was destroyed in 70 CE during the siege of Jerusalem. Passover became more focused on the Passover meal, or the seder. Aside from the seder, there are many customs associated with Passover, which vary from denomination to denomination (in Judaism, there are the Reform, Orthodox, and Conservative branches) and from family to family.

This article on My Jewish Learning says that it is common for families to do spring cleaning before the Passover meal. People also do not eat leavened bread, because the Israelites leaving Egypt didn’t have time to let their bread rise. There are special religious services held in synagogues. The article concludes that “[t]he divine redemption of the Israelites thus becomes the blueprint for the Jewish understanding of God and divine morality and ethics.” And so Passover has many lessons for how to treat one’s neighbors.

It is also interesting that the Jewish people are not the only ones who found importance in the exodus story. Throughout American history, Black Christians found the story incredibly powerful. As Gayraud Wilmore writes in Black Religion and Black Radicalism, missionaries and slavers alike told Black people that God demanded subservience and unconditional submission from slaves. But in the exodus, God chooses a race of enslaved people as His people and liberated them from their bondage. This became a central story of liberation for what would come to be known as the “Invisible Institution.”

II. The Promised Land and Zionism

However, the story of liberation did not stop there. After God freed the Israelites from slavery, He brought them to the land of Canaan. Now, Canaan was already inhabited by several people groups. In the book of Joshua (though the book of Deuteronomy tells the story quite differently), God commands Israel to essentially genocide these people groups (see Joshua 11:20-23).

So though the Israelites were an oppressed people group who were liberated by God, they also wiped out the Canaanites (at least according to the book of Joshua).

There is something to be said about the fact that Deuteronomy shows that this sort of genocide never really happened. Because throughout Deuteronomy, Canaanites are still around. Evidence has also surfaced that significant portions of the Canaanite population survived the Israelite conquest. Most of their descendants reside in modern day Lebanon. So interpreters must treat the Hebrew Bible with more nuance and specificity. The message one gets from reading the book of Joshua by itself does not seem to be the only one.

Nevertheless, the ensuing conquest of Canaan became a defining narrative for the Zionist agenda. You have a land (Canaan, Palestine) with people already occupying it (Canaanites, Palestinians). There’s a group that claims they are God’s people (Israelites, State of Israel). And there is also an experience of slavery or trauma from which the Jewish people are seeking a home (Egypt, the Holocaust). It is no wonder that Zionism is so convincing to those who value the story of the exodus.

The Promised Land and Manifest Destiny

Politicizing the exodus story to justify settlements and expansion is not unique to the State of Israel. Donald M. Scott talks about how America viewed the exodus story in his article titled “The Religious Origins of Manifest Destiny.” Scott, a historian at Queens College, writes that the idea of Manifest Destiny was never a purely political ideology.

Manifest Destiny held that America had the right to expand its power and populace from sea to shining sea. The land rightfully belonged to the White settler. Necessarily, this meant that the Indigenous peoples who had occupied these lands centuries before were in the way.

But Manifest Destiny was religious in origin, as Scott points out. America has a destiny. But who chose America? Who gave America its destiny? God did. But God not only gave America the divine right to conquer the “promised land.” Under Manifest Destiny, God becomes the ideological justification for eradicating and forcefully displacing Indigenous nations.

There’s a piece of land (Canaan, the “New World”). Turns out, there’s people already living there (Canaanites, Indigenous nations). There’s a group who claims to be God’s people (Israelites, White settlers). And there’s an exodus from which that group is coming out of (Egypt, religiously oppressive Europe).

If the Passover story shows us a story of the redemption of an oppressed people, the story of the exodus shows us a people who replicates the very oppression it escaped from.

III. Naomi Klein: Environmentalist and Author

Enter Naomi Klein. Klein is an accomplished Jewish professor at the University of British Columbia. She holds tenure as the professor of Climate Justice at UBC. Klein is a prolific writer, and has authored multiple books. A decorated journalist, Klein has received recognition for her work as a public intellectual.

On the second night of Passover, April 23, thousands of protesters gathered in Brooklyn, New York. Most of the protestors are Jewish. The New Yorkers called their gathering a “Seder in the Streets to Stop Arming Israel.” The protest was followed by hundreds of arrests, and a foreign aid package was passed in the Senate. Out of the $95,000,000,000 approved for foreign aid, $17,000,000,000 was approved to aid Israel in weaponry and security.

It was here at this protest that Klein gave her speech on the meaning of Passover.

The False Idol of Zionism

Naomi Klein’s speech centers on the concept of idolatry. She opens with reflections on the story of the Golden Calf. Not long after God liberated Israel from Egypt, Moses went up Mount Sinai to talk with God. At Sinai, God gave Moses the famous Ten Commandments as rules for national life. But when Moses went down, he saw Israel worshipping a calf made of gold.

In the Old Testament, idolatry is perhaps the most severe sin against God. Prohibition against idolatry (or worshipping gods other than God) is actually the first commandment! (Many Jews enumerate the Ten Commandments differently than Christians do. Christians identify the first commandment as “you shall have no other gods before me,” (Ex. 20:3) while the Talmud identifies the first commandment as “I am the Lord your God, who brought you out of the land of Egypt” (v. 2).)

For Klein, Zionism is the Golden Calf of today’s Israel.

[Zionism] is a false idol that takes our most profound biblical stories of justice and emancipation from slavery, the story of Passover itself, and turns them into brutalist weapons of colonial land theft, roadmaps for ethnic cleansing and genocide. It is a false idol that has taken the transcendent idea of the Promised Land, a metaphor for human liberation that has traveled across faiths to every corner of this globe, and dared to turn it into a deed of sale for a militarist ethnostate.

Though many mistakenly (or intentionally) say that being against Zionism is anti-semitic, Klein says that Zionism is really anti-Jewish.

The State of Israel as the New Egypt

Klein goes on to say that the modern State of Israel has essentially become the new Egypt. Just as the Pharaoh who “did not know Joseph” ordered Israelite children to be killed, so too does the State of Israel today see “Palestinian children not as human beings, but as demographic threats.”

Additionally, Zionism has led the Jewish people to compromise on fundamental values. Klein declares that the support for the Israeli state has “led far too many of our own people down a deeply immoral path that now has them justifying the shredding of core commandments — ‘Thou shall not kill,’ ‘Thou shall not steal,’ ‘Thou shall not covet.'” And as she points out, these are the very commandments that Moses brought down from Sinai when he saw the Israelites worshipping their golden calf!

Klein laments the killing of Palestinian academics and the complete destruction of Gazan universities—as well as the tens of thousands of lives lost at the hands of Israel. She criticizes the perpetual warfare and fear that Israel benefits from. She is grieved at how long Zionism as an ideology has persisted in the broader Jewish community. And given the then-yet-to-be-passed aid package, she speaks against the weapons and donations that feed the Zionist project.

She continues:

This here is our Judaism. . . . We don’t need or want the false idol of Zionism. We want freedom from the project that commits genocide in our name. We want freedom from the ideology that has no plan for peace, except for deals with the murderous, theocratic petrostates next door, while selling the technologies of robo-assassinations to the world. We seek to liberate Judaism from an ethnostate that wants Jews to be perennially afraid, that wants our children afraid, that wants us to believe that the world is against us so that we go running to its fortress.

Conclusion: A Modern Moses?

Klein is not just somewhat against Zionism. She doesn’t just think that it is a disagreeable ideology. No. She views it as genocidal and anti-Jewish.

And Klein is not alone. She is accompanied by thousands of other Jewish people and their allies, hundreds of whom were arrested after the protest. In protests in America and across the world, Jewish people are often the most vocal in speaking out against Israel’s crimes and atrocities.

One could say, as Klein does, that Judaism is encountering a new exodus. As Klein puts it, “We, in these streets for months and months, we are the exodus, the exodus from Zionism.” And whereas Moses told Pharaoh thousands of years ago to let his people go, the modern Moses today goes even further. “[T]o the Chuck Schumers of this world, we do not say, ‘Let our people go.’ We say, ‘We have already gone, and your kids, they are with us now.'”