By Emmanuel Cantor

By Emmanuel Cantor

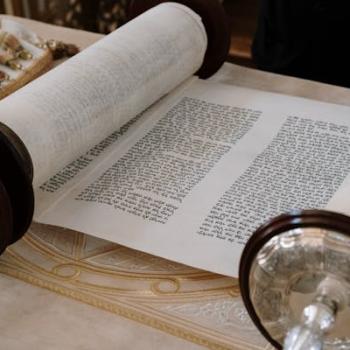

Parashat Vayak’hel-Pekudei (Exodus 35:1-40:38)

I vividly remember being in my third-grade Jewish day school class and learning about the Omer, the ritual counting of the days between Passover and Shavuot. Perhaps I had a contrarian impulse that day, as the first thing that I remember is rolling my eyes. I assumed that counting days would be a little boring. Then my teacher taught the class a song to sing before we counted, a tune set to the Torah verses describing the omer. I loved the drama of the melody and the rhythm of the chanting. Thanks to the song, I grew excited to count the omer each morning.

The power of art to transform the mundane into the magical— as it did for me in my third grade classroom—is on full display in this week’s double-parashah, Vayak’hel-Pekudei. The portion describes the building of the mishkan, or Tabernacle, and its stars are artists—the architect Bezalel and his assistant Oholiab, and the unnamed women who weave blue, purple, and crimson yarn into the mishkan‘s vibrant curtains.

“The role of the artist is to make the revolution irresistible,” taught the Black Arts Movement writer and activist Toni Cade Bambara. Although rooted in her life and work, we can apply Cade Bambara’s words to Vayak’hel-Pekudei as well. In the aftermath of last week’s Golden Calf reading, the newly-liberated Israelites appear unable to get onboard with the spiritual revolution of Sinai. This week, the artists Bezalel, Oholiab, and the women who weave make that revolution irresistible.

The Golden Calf provides a backdrop to the focus Vayak’hel-Pekudei places on art and artists. The artists are described seven times as chacham lev, or wise-hearted. Bezalel, in particular, is noted for his “divine spirit of skill, ability, and knowledge in every kind of craft” (Ex. 35:32, NJPS). This emphasis on Bezalel’s artistry is in contrast to Aaron’s response to Moses when confronted over his role in fashioning the Golden Calf.

They said to me, ‘Make us a god to lead us; for that fellow Moses—the man who brought us from the land of Egypt—we do not know what has happened to him.’ So I said to them, ‘Whoever has gold, take it off!’ They gave it to me and I hurled it into the fire and out came this calf!” (Ex. 32:23-24, NJPS).

Aaron’s “out came this calf” line is often read as an attempt to exonerate himself, a “dog ate my homework” style excuse. Yet, Aaron’s explanation also reflects a creative process that lacks proper time, space, skill, and intention. Rashi, the 11th century commentator, emphasizes an absence of artistic creativity in his commentary on the verse: “he (Aaron) took from them and cast in a mold, and made it into a molten calf” (Ex. 32:4, NJPS). Citing an Aramaic translation by Onkelos, Rashi imagines Aaron using a mold that can make multiple copies of the same gold object, such as letters or small figurines. In this reading, the Golden Calf is not only a betrayal of God’s covenant with the people. It is also easily-copied, unoriginal art.

Or perhaps, not really art at all. In a 2002 piece for The Guardian, novelist and critic Jeanette Winterson distinguishes between art and the mass production of the market. She writes:

Mass production is about cloned objects. Art is about individual vision. Individuals can work together, as they must in theater or opera, or where assistants work under a master, or they can work alone. However it happens, art is never a factory or a production line.

In Winterson’s model, the molded Golden Calf is not the art of individual vision but a “cloned object” of the production line, albeit an ancient one. By contrast, the mishkan is the opposite: an original, creative work. To this point, a Midrash wonders why God did not command Moses to construct the mishkan as a canvas tent with four poles—an easy-to-copy model. In response, the rabbis imagine that on Sinai, God showed Moses fires in shades of red, green, black, and white. The following parable is then offered.

This is like a king who had a splendid garment made of jewels. He said to his personal friend, ‘Make me one just like it!’ He answered, ‘My lord the king, can I make one like it?’ The king replied, ‘I remain in my glory, but you have your materials.’ Similarly, Moses said to God, ‘My God, can I make anything like these fires?! God replied [by listing the materials for making the mishkan], ‘Blue purple and crimson yarns, fine linen…’ (Bamidbar Rabbah 12:10, translated by Dr. Avivah Zornberg).

In this Midrash (parable), the king, as a stand-in for God, urges an artistic friend to replicate a bejeweled garment. While the friend pleads that he is unable to duplicate such an exquisite work, the king insists that it is the friend’s artistic creativity, or “materials,” that the king most desires.

So too, Moses receives a model for the mishkan. Yet unlike the Golden Calf, it is a model impossible to copy. This is by God’s design. Inspired by divine fires, Moses will have to creatively use “his materials” to make the mishkan. It will be a work of art. And this art will make the revolution of Sinai irresistible.

Elsewhere in her piece, Winterson speaks of art’s invitation for us to slow down, thereby expanding our awareness.

The time you spend on art is the time it spends with you; there are no shortcuts, no crash courses, no fast tracks. Only the experience. Art can’t change your life; it is not a diet programme or the latest guru—it offers no quick fixes. What art can do is prompt in us authentic desire. By that I mean it can waken us to truths about ourselves and our lives; truths that normally lie suffocated under the pressure of the 24-hour emergency zone called real life.

Today, I still sing the song I was taught in third grade before I count the omer. The omer blessing can be rattled off in a matter of seconds, but there is no shortcut to the song. The melody invites me to slow down, calling my awareness to the transition between Passover and Shavout, Egypt and Sinai. And while the golden calf pops out of the fire in only one short verse, the mishkan—thanks to Bezalel, Oholiab, and the “wise-hearted women”—is designed and built over hundreds of verses. There are no shortcuts, only real life.

Emmanuel Cantor is a fourth-year rabbinical student at Hebrew College. As a student rabbi, he has served a number of Jewish communities, most recently Congregation Dorshei Tzedek and the Slifka Center for Jewish life at Yale. Before rabbinical school, Emmanuel worked as a community organizer for Jews United for Justice and lived in an Avodah Bayit. He earned his BA at Yale, where he majored in Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies, and is an alum of Yeshivat Maale Gilboa in northern Israel.