- Trending:

- Olympics

- |

- Forgiveness

- |

- Resurrection

- |

- Joy

- |

- Afterlife

- |

- Trump

RELIGION LIBRARY

Christianity

Modern Age

The turmoil of the 20th century proved a trying time for Christianity. Due to its global spread, there were Christians on all sides of nearly every major conflict of the century, from two world wars, through the use of nuclear bombs in Japan, to wars in Korea and Vietnam, to the anti-colonial conflicts in Latin America, North Africa, Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and the Middle East. Marxist governments came to power and enforced secular culture throughout the historic areas of the Eastern Churches and in China. Christians were challenged to redefine their morals and their ideologies in response to these upheavals.

New movements emerged in the 20th century: ecumenism, liberation theology, Pentecostalism, and fundamentalism. Each in their own way represented a thoughtful response to the question of the role of Christians in the world. The 20th century also saw the development of a shift of a center of gravity to the global South.

The spirit of ecumenism is nearly as old as Christianity itself. The First Ecumenical Council at Nicaea in 325 was so called because bishops came from all parts of the Christian world. Twentieth-century ecumenism dates to 1910 when several missionary societies convened a meeting in Scotland designed to develop a common missionary strategy that could contribute to the healing of divisions and coordinate a mutual commitment to action and service to the world. Between 1910 and 1948, a number of denominations established international church councils.  National church councils such as the British Council of Churches and the National Council of Churches of Christ in the U.S. were formed so that various Protestant groups could work together on issues of common interest. The World Council of Churches was founded in 1948.

National church councils such as the British Council of Churches and the National Council of Churches of Christ in the U.S. were formed so that various Protestant groups could work together on issues of common interest. The World Council of Churches was founded in 1948.

The European experience of Nazism convinced the churches that the world needed a unified Christianity with the strength to resist further terrors. Over the next five decades, anti-colonial struggles and the resulting civil wars had a profound effect on the membership of the international federations and the World Council of Churches. Many of the member churches in the so-called first world built strong bonds of solidarity with churches in the developing world that were campaigning for national independence, self-determination, and economic development. These campaigns were tightly linked to a theology from the developing world called liberation theology. Liberationist movements found allies and partners in the ecumenical movement largely because of the increasing numbers of activists and intellectuals from the developing world in leadership roles in the federations and councils.

Beginning in Latin America, and emerging from local Christian responses to the conditions of extreme poverty and suffering, liberation theology called for all people to stand with Jesus on the side of the poor and the oppressed. Based in their practical experiences of combating illiteracy and helping the desperately poor to read the Bible, these theologians came to see the teachings of Jesus with new eyes. They saw fresh relevance in Jesus' love for the poor, and his efforts to ease their suffering.

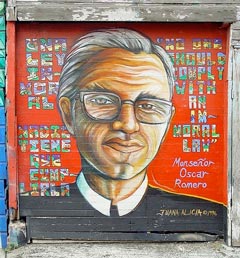

Beginning in Latin America, and emerging from local Christian responses to the conditions of extreme poverty and suffering, liberation theology called for all people to stand with Jesus on the side of the poor and the oppressed. Based in their practical experiences of combating illiteracy and helping the desperately poor to read the Bible, these theologians came to see the teachings of Jesus with new eyes. They saw fresh relevance in Jesus' love for the poor, and his efforts to ease their suffering.  Latin American liberation theology was found in the scholarly writings of such teachers as Gustavo Gutiérrez and José Miguez Bonino, in the poetry and activism of revolutionary priest Ernesto Cardenal, in the work of literacy teacher Paolo Freire, and in the life and ministry of martyred Roman Catholic Archbishop Oscar Romero.

Latin American liberation theology was found in the scholarly writings of such teachers as Gustavo Gutiérrez and José Miguez Bonino, in the poetry and activism of revolutionary priest Ernesto Cardenal, in the work of literacy teacher Paolo Freire, and in the life and ministry of martyred Roman Catholic Archbishop Oscar Romero.

Liberation theology spread to the United States, where James Cone penned his A Black Theology of Liberation in 1970. Black liberation theology was furthered by the teaching and preaching of such American intellectuals as Cornel West and Dwight Hopkins, and transformed by women such as Jacquelyn Grant, Katie Cannon, and Delores Williams.  Feminist liberation theology, African liberation theology, and Korean Minjung theology were among other compelling and inspiring explorations of incarnation and redemption. It was not long before liberation theologians began extending their ideas on human freedom and dignity to questions of environmental protection and health, as well as interfaith understanding and cooperation.

Feminist liberation theology, African liberation theology, and Korean Minjung theology were among other compelling and inspiring explorations of incarnation and redemption. It was not long before liberation theologians began extending their ideas on human freedom and dignity to questions of environmental protection and health, as well as interfaith understanding and cooperation.

Americans have made significant contributions to ecumenical and liberationist movements in the forms of ideas, donations, volunteer efforts, advocacy, and influential indigenous forms of ecumenical and liberation theology. But ecumenism was largely rooted in European churches and traditions, while liberation movements found their initial expressions in poverty-stricken communities of Latin America. Another 20th-century ideology, fundamentalism, was rooted in American history and traditions, and is still in many ways distinctively American.

Fundamentalism appeared among American evangelical communities in 1920. World War I had proven enormously disruptive to longstanding cultural traditions in most parts of the world; in America, some Christians felt that American culture had lost its way. The ordered worldview of the Victorians was being replaced by the boisterous experimentation of the jazz age, while communism and atheism were winning new adherents. The introduction of the theory of evolution to school curricula threatened to undermine the authority of the Bible, while theological liberalism sought rapprochement with relativistic notions of morality and truth. Academic disciplines of higher criticism began to question the historicity and legitimacy of scripture.

By the 1940s, fundamentalist groups had organized in a campaign to place the precepts and values of evangelical Christianity at the core of American culture. Strategies included founding new ministries and Bible institutes, and reaching a broad audience through radio programs. Due to tensions with the broader movement of American evangelicalism, which was open to communication with theological liberalism, fundamentalists became separatists, resisting ecumenical efforts at Christian unity. Separatist fundamentalism remained politically inactive until the 1970s, when the formation of the Moral Majority, a political advocacy group devoted to lobbying for conservative Christian values, united traditional fundamentalist concerns with contemporary political issues, such as women's liberation, gay and lesbian activism, and abortion.

Pentecostalism has also changed the face of Christianity. Amidst a period of intense renewal at the beginning of the 20th century, Pentecostal and charismatic congregations developed, focusing on the gifts of the Holy Spirit. Pentecostalism has embodied itself in numerous denominational entities, but its core teachings about the active work of God in healing, prophecy, and other spiritual gifts has also penetrated many other Christian denominations, from Roman Catholicism to a variety of Protestant groups.

Pentecostalism has also changed the face of Christianity. Amidst a period of intense renewal at the beginning of the 20th century, Pentecostal and charismatic congregations developed, focusing on the gifts of the Holy Spirit. Pentecostalism has embodied itself in numerous denominational entities, but its core teachings about the active work of God in healing, prophecy, and other spiritual gifts has also penetrated many other Christian denominations, from Roman Catholicism to a variety of Protestant groups.

As we move into the 21st century, Christianity still wrestles with the challenges of conflict and war, desperate poverty and political oppression, and new challenges from scientific discovery, humanism, and secularism. The United States has seen the rise of charismatic movements, mega churches, hybrid denominations, and new denominations. Immigrants from all over the world have introduced new religious ideas and practices, and Christians enjoy an unprecedented degree of interfaith encounter.

Study Questions:

1. What is ecumenism? When did it begin, and what does it look like in contemporary society?

2. What is liberation theology? What is it based on?

3. Why could it be said that fundamentalism has a direct correlation with American morality?