- Trending:

- Olympics

- |

- Forgiveness

- |

- Resurrection

- |

- Joy

- |

- Afterlife

- |

- Trump

Pentecostal Origins

Beginnings

Pentecostalism's beginnings are rooted in the description of "tongues of fire" that fell upon the heads of Jesus' followers who gathered to pray in Jerusalem around the time of the Jewish Festival of Weeks (Pentecost). The Book of Acts (2:4) continues, "All of them were filled with the Holy Spirit and began to speak in other tongues as the Spirit enabled them." The Book of Acts, along with Paul's commentary and instructions regarding the other nine gifts of the Holy Spirit, form the central tenets of Pentecostalism.

From this description, what Pentecostalism is, where it began, and how or if it still continues into the present are all issues up for theological and historical debate. What can be described as Pentecostal beginnings might better be framed as "charismatic" activity, which was attested to hundreds and hundreds of times over the span of the formative years of the Church. This is important to note, since one of contemporary Pentecostalism's key arguments for its validity as a core part of Christian history is its existence as part of an unbroken stream of supernatural activity spurred by the direct experience of the Holy Spirit, thus tying all Pentecostals back to the Book of Acts.

Most of this Pentecostal activity in the early Church followed familiar biblical patterns focusing on prophecy, visions, healing, and exorcisms (casting out of demons). Specific descriptions of speaking in tongues (glossolalia) are often nuanced, inferred, but there are some descriptions of speaking and singing in languages that were not known to the speakers (xenoglossia). Since glossolalia and xenoglossia are both a part of Pentecostalism's contentious history, it should be noted that both phenomena were described in early Church circles. Suffice to say, historically there have been detractors who have doubted that either of these phenomena is possible, and they often posited that Church leaders who had experienced such phenomena were either deluded or deceived, and that most were theologically very dangerous.

Montanus, a 2nd-century Church leader, was considered a heretic because of his claims to receive direct revelations from the Holy Spirit. Montanus, and his female companions, Priscilla and Maxmilia, preached throughout Phrygia (modern-day Turkey), that direct revelations from the Holy Spirit had given them the ability to prophesy and to receive visions, and a renewed zeal for prayer and fasting. Challenging the notion that one did not need the authority of the Church to be a faithful Christian, Montanus and other leaders who believed that the Holy Spirit could lead them to the truth without the guidance of the Church's authority were simply too dangerous for the Church to accept. Most, if not all, of Montanus's followers were branded as heretics, including noted Church leader Tertullian.

Montanus is probably one of the more well-known of the early Church proponents of direct experience with the Holy Spirit, but not all such would be labeled as heretics. Church leaders who claimed to have had some charismatic experience included noted heretic-hunter Irenaeus (c. 115-202), Origen (c. 185-254), Augustine (354-430), Symeon (Eastern Orthodox) (949-1022), and even Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274); they are joined by a host of early and medieval mystics of the 15th and 16th centuries.

Many of these figures would describe phenomena that contemporary Pentecostals would identify as Pentecostal gifts of the Spirit, or at least, Pentecostal-like phenomena. Irenaeus was believed to have had the gift of prophecy, discernment of spirits, and exorcism. Origen was reported to have healed people, exorcised demons, and engaged in other assorted "signs and wonders." Some mystics, including Eastern Orthodox figures Symeon the New Theologian and Seraphim of Sarov, discussed phenomena such as "baptism of the Holy Spirit," uncontrollable bouts of crying, and visions of the Transfiguration (akin to the description in Matthew 17) overtaking them for hours on end.

Some significant Church leaders did describe what Pentecostals today would believe is glossolalia. Francis Xavier (1506-1552), Vincent Ferrer (1350-1419), Ignatius of Loyola (1491-1556), and Teresa of Avila (1515-1582), among others, describe something akin to Ignatius's description of prayer: "During the interior and exterior loquela (speech) everything moves me to divine love and to the gifts of loquela divinely bestowed." (Spiritual Diary, #222).

Despite the controversy that followed such experiences (nearly all who admitted having these experiences risked attracting the wrath of Church officials charged with rooting out all suspected challenges to ecclesiastical authority), some of the most well-known Christian figures have reported these experiences, made these practices a part of their theological legacies, and often paid a heavy price for insisting that they had direct access to revelation through the Holy Spirit. Throughout history, those who claimed these experiences were often targeted as heretics, threatened with persecution (such as the Inquisition), and, if they posed enough risk to Church authority, were removed from any mantle of leadership. Thus, groups as varied as the Spanish "alumbrados" (Enlightened Ones), the Jansenists, or a legion of Christian mystics, have been made to answer for taking what was supposed to be the domain of the Church (access to revelation), and making it available to anyone who asked for it.

By the mid 1700s, early forms of contemporary Pentecostalism began to emerge from what began as a reformation movement within Anglicanism; they resulted in a global movement that has influenced nearly every different tradition of Christianity.

Influences

A variety of confluent streams created Pentecostalism. The movement owes much to Methodist, Pietist, and the Holiness movements that stretch from the 18th to 19th century. These movements shared a desire to deepen the experience of conversion by overcoming sin through a continual work of holy living. Articulating Christianity's appeal to the masses as a "religion of the heart" did not begin with John Wesley, but he certainly can be credited for founding one of Christianity's most enduring movements.

John Wesley (1703-1791) promoted Christian perfection as a model of holy living. What began as a reform movement within the Anglican Church became a global movement stressing grace, sanctification, and social reform. Of particular note was John and his brother Charles's trip to the colony of Georgia in 1735, where their desire to convert Native Americans ran into the realities of colonial and missions politics. On his way to Georgia, John was introduced to and became impressed by the steadfast faith displayed by Moravian missionaries traveling with him. This relationship would continue for the next several years even as Wesley failed at becoming a major force in the conversion of Native Americans and left to return to England. What did not disappoint him was the fervency and pietism of his Moravian friends.

German Pietism, especially that of the Moravians, stressed a faith life that sought to overcome sin. In Wesley's case, it was this emphasis on the victory over sin as well as the Pietist emphasis on the continuing miracles described in the New Testament that attracted him. Pietism especially focused on healing as a part of the life of every Christian, and linked this to the idea that sickness originated in sin. Therefore, if sin could be overcome, then health was part of the life that all Christians could claim for themselves. What Wesley, the Pietists, and later movements such as the Holiness movement all stressed was that living out the Christian life meant that one had to take on the life of Jesus, accepting the scorn as well as the victory that emanated from living a sacrificial life of rigorous practices (prayer, fasting, Bible reading, piety).

Another significant influence in the stream of Christian spirituality that eventually led to the development of Pentecostalism was the British Keswick movement. The Keswick or Higher Life movement began in England in the 1870s. Seeking to reinvigorate the Wesleyan notion of Christian perfection, Keswick proponents believed that there was an essential component to life after conversion, mainly that being "sanctified" or "filled with the Holy Spirit" was part of seeking a deeper faith. The movement was promoted on a variety of fronts, especially by William Boardman, who began holding meetings to promote the "Higher Life" in Keswick. Boardman brought in other influential people who began writing on the topic of Christian perfection and the Higher Life, and soon the movement began to influence many of the Methodist churches in England. The meetings began in 1875 and continue to this day.

Before there was an established Holiness movement (an offshoot of Methodism), there were several particular events that are now seen as precursors to Pentecostalism. It is worth noting them since they are both theologically and experientially significant to the discussion of the streams that influenced Pentecostalism.

In 1801 in Cane Ridge, Kentucky, Barton Stone, a preacher who had founded his own Restorationist movement with Alexander Campbell (later to be known as the Churches of Christ and Disciples of Christ movements among others), had a series of revival meetings stressing holy living and rededicating one's life to Jesus. These have been described as precursors to Pentecostal revivals more than a hundred years later. Between 20,000 and 40,000 people attended these meetings between 1801-1804. People fainted, began shaking, singing, and exhibiting other phenomena such as barking like animals.

The significance of these meetings is found in the idea that Holiness teachings advocating the eradication of sin seem to precede the outbreak of phenomena. With Pentecostalism's growth and maturation, these phenomena have been given theologically significant responses. In common parlance, fainting in a time of worship is called being "slain in the Spirit." Being overtaken by the Holy Spirit has been described as akin to shaking uncontrollably.

Some of the different Christian denominations in the U.S. during the 19th century began to produce a variety of new leaders, like Phoebe Palmer and William Boardman, who focused on what they would call "Christian Perfection." These writers did not leave their denominations, but introduced movements within them that centered on lives of holiness. Phoebe Palmer associated sanctification as a baptism of the Spirit with the onset of spiritual power that would make possible a life of holiness.

In 1870, Asa Mahan, teacher and leader of the Oberlin Holiness movement, described the "baptism of the Holy Ghost" as an act by which the Holy Spirit accomplishes sanctification for the faithful. Mahan and Charles Finney, another 19th-century revivalist, began articulating a language of the Holy Spirit that would later become the theological underpinnings of Pentecostalism's emphasis on the active work of the Holy Spirit. They taught that the Spirit imbued people with supernatural gifts intended to serve as an outward sign of inward sanctification.

Holiness revivals spread through the work of individual evangelists and writers such as Palmer and Mahan, but one of its most successful avenues for the dissemination of Holiness theology was the camp meeting. As early as 1867, these camp meetings were calling people together to "realize together a Pentecostal baptism of the Holy Ghost." Themes at these meetings, themes running throughout much of the Holiness literature of the time, made a decisive shift from traditional Methodist themes to the theme of the role of the Holy Spirit in imbuing power.

The blurring of the lines between holiness and power, the former related to issues of sanctification and the latter to signs of the Spirit, marked the permanent schism between Holiness movements and early Pentecostal stirrings in the south and midwest U.S. The ministry of Benjamin Harden Irwin, founder of the Fire-Baptized Holiness Church, began to join holiness and experience, and began equating the sanctification process with the experiential operation of the Holy Spirit. Irwin spoke of a "baptism with fire" obtainable by faith; this was a separate act from the process of sanctification that early Holiness and Methodist preachers taught. That one could be free of sin, perfected by God, did not seem to be the key point of discord any longer within the Holiness movement. The point of discord was a movement that stressed power over sin through defining physical manifestations brought on by the Holy Spirit. By the early 20th century, those who preached Pentecostal experiences, like speaking in tongues, were separating from Holiness churches, which pursued issues of sanctification.

Founders

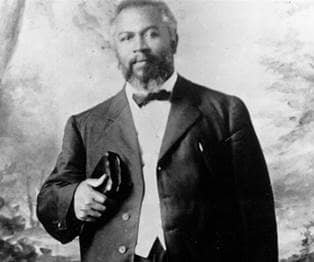

William J. Seymour (1870-1922) was the son of former slaves born in Louisiana. After working a series of jobs, and exploring the call to ministry in several churches, Seymour moved to Indianapolis and joined Daniel S. Warner's Church of God movement (in Anderson, Indiana), nicknamed the "Evening Light Saints." This intentionally multiracial movement was deeply rooted in ideals of social reform and allowed Seymour to begin his pastoral career preaching to mixed audiences as he formed his own ideas about race and faith.

Seymour traveled to Houston to take classes at the Bible school of fellow Pentecostal founder, Charles F. Parham. In accordance with the racial norms of 1905, as an African American, Seymour had to wait outside the classroom and listen to the lecture. What he heard from Parham seemed to convince him of the necessity of another experience after sanctification that would be accompanied by the evidence of speaking in tongues. Seymour was invited to preach at a small Holiness church in Los Angeles, but found a less than receptive audience when he began preaching about the Pentecostal baptism. By all accounts, Seymour had not experienced the baptism yet, which was unusual and caused his Holiness congregation to wonder why he would be preaching about something he had yet to experience. A small group from the Holiness church decided to support Seymour's preaching and allowed him to use one of their homes, on Bonnie Brae Street, as a base where he would, in effect, begin the American Pentecostal movement in 1906.

Seymour's preaching drew huge crowds, so large that they moved to an abandoned African Methodist Episcopal church in downtown Los Angeles, the Azusa Street Mission. Hundreds came to hear about this new outpouring of the Holy Spirit, and often the meetings spilled out into the streets. Finally, after months of preaching and praying for such an outpouring, Seymour-along with a church full of witnesses and pastoral staff-experienced the baptism of the Holy Spirit on April 9, 1906, accompanied by speaking in tongues. The spiritual nature of the event would have been revolutionary enough if it hadn't also been combined with the social nature of the meetings. Different races and ethnicities as well as women and men worshipped side by side. Such revolutionary happenings in Los Angeles were welcomed by Seymour, who viewed racial egalitarianism as part of his mission. Unfortunately that unrestricted spirit would not outlast the Azusa Street revival, which lasted from 1906 to 1909.

Thanks to the work of the church stenographer, Seymour's sermons and thoughts about the Azusa Street Revival were preserved and transmitted through the pages of the mission's newspaper, The Apostolic Faith. In addition, Seymour attempted to codify the theology of Azusa Street in a book called Doctrines and Discipline of Azusa Street Apostolic Mission of Los Angeles. But according to historian Douglas Jacobsen, Seymour's writing is little more than the African Methodist Episcopal's book of discipline with a few of Seymour's thoughts interspersed throughout the document.

Not everything went well at Azusa Street. Since the much heralded revival, which was for many a sign of the end times, occurred at a predominately African American church, Seymour's legitimacy as a Pentecostal leader was in question from the beginning. Seymour not only survived the local criticisms from the religious and civil leadership of Los Angeles, but he survived two attempted coups of his pastorate, one by his old teacher, Charles Parham, and another by Chicago-based evangelist, William Durham.

The realities of turn-of-the-century Los Angeles forced Seymour to concede that if the Azusa Street Mission were to survive past the revival stage, it would soon have to revert back to what it started out as-an African American congregation with "colored" leadership-to ensure its survival amid the hostile racial atmosphere of southern California. Seymour and his wife Jenny ran the church; William died in 1922, Jenny in 1931. The property was sold to pay back taxes, and in what would be a cruel twist of fate, this Pentecostal paradise was torn down for a parking lot.

Charles F. Parham is the other major figure that vies for the title of founder of Pentecostalism. Parham's Topeka, Kansas mission, Bethel Bible, was the scene of one of most significant events in the early history of Pentecostalism. On January 1, 1901, a Bible student, Agnes Ozment, received the baptism of the Holy Spirit with evidence of speaking in tongues. Though Parham was not there on that day, he had been preaching the baptism of the Holy Spirit for years and had been trying to find a way to synthesize all the disparate theological strands of sanctification and the work of the Holy Spirit.

Parham was one the first of the early Pentecostal leaders to meld together Spirit baptism and speaking in tongues. Parham's solution was to suggest that there was another experience after sanctification that all Christians should earnestly seek after as a sign that they have received "power from on high" as described in the Book of Acts. The baptism in the Holy Spirit was evidenced by speaking in tongues. This is called the doctrine of initial evidence. For Parham, tongues were known languages that were given to people to enable to go out onto missions. This phenomenon, xenoglossia, was not generally accepted beyond Parham's initial discussion of it. What was accepted was the idea that you knew that you had been baptized in the Holy Spirit when you spoke in a language that you did not know.

Parham's ministry after the Topeka, Kansas event seems like a blur of activity during which Parham built up networks of churches of the Apostolic Faith, attempted to take over Seymour's Azusa Mission, and in 1907, was arrested on a charge of sodomy. Parham's reputation never recovered and he spent the rest of his ministry days in relative obscurity focused seemingly on biblical themes of race, white supremacy, and eschatology.

Sacred Texts

Pentecostalism, like other Protestant communities, embraces the 66 books of the Bible as a guide to faith and practice. It relies heavily, however, on the Book of Acts as a blueprint for the Pentecostal experience. Other foundational scriptures include Paul's first Letter to the Corinthians, especially chapters 12-13 where the gifts are discussed. Some sections of the Hebrew Bible, like Joel 2: 28-29, receive much attention.

Since there are no other scriptures that Pentecostalism adheres to, it may be helpful to briefly examine two foundational texts and draw some comparisons between how Pentecostals and other conservative Protestants interpret them. It will also be helpful to discuss how Pentecostals interpret certain passages differently amongst themselves. From the movement's earliest days, schism has been an option for Pentecostals who have described their disagreements as part of a revelation from God rather than as mere differences of interpretation.

Taking the foundational text first, Acts 2:4, Pentecostals place most of their theological emphases on this scripture, which describes a meeting that Jesus' followers had in Jerusalem when the tongues of fire appeared over their heads, the Holy Spirit filled them, and they began to speak in other tongues as the Spirit gave them utterance. This description, along with a few others (especially Acts 10:10), gives Pentecostals the theological support for adhering to the doctrine of initial evidence, that Spirit baptism is demonstrated by speaking in tongues (though as we shall see later, most Pentecostals loosely adhere to that doctrine as a matter of faith and practice).

The story in Acts is important not only for its experiential description, but also for what it says in terms of Pentecostal theology. Jesus' admonition that he would not leave his followers without an advocate, a comforting presence (John 14-16), is seen as fulfilled in the Acts passage. These sections that fulfill the prophetic nature of Jesus' words, and especially the Old Testament passages that, for Pentecostals, foreshadow the Pentecostal movement (e.g., Joel 2:28-29), are particularly important. They place Pentecostalism squarely within the Christian tradition, legitimating its existence regardless of whether other Christian bodies agree with the experiential nature of their faith. Because Pentecostals are as rooted in the scriptural texts as other evangelicals, arguing with the text become a self-defeating exercise.

Passages such as Joel's are always subject to interpretation and revision based on one's social and cultural lens; the Joel passage has always been a kind of theological double-edged sword. Joel 2:28-29 reads:

28 And afterward,

I will pour out my Spirit on all people.

Your sons and daughters will prophesy,

your old men will dream dreams,

your young men will see visions.

29 Even on my servants, both men and women,

I will pour out my Spirit in those days.

These two passages contain many problems for Pentecostals, problems that they have still not fully resolved. Pouring out the Spirit on all people, for some Pentecostals, is a universal statement, meaning that believers and non-believers alike will somehow be touched by this most supernatural of experiences, which leads to prophecy, dreams, and visions. So, does that create a pathway for universal salvation in Pentecostal theology? Such talk has been heretical for some time, but serious theological discussion on what that sentence means has begun to slowly unravel the exclusive claims that the Spirit is poured out only on those whom contemporary Christians believe are worthy.

Another major issue in this passage is the gender equity explicitly guaranteed in the text. If both sons and daughters will prophesy, and all of the servants of God will have the benefit of having the Spirit poured out on them as a sign of the last days, it follows that there are definite roles for women in ministry. As such, women have had authoritative roles in Pentecostalism that they have not had in other branches of Christianity. The idea that women are endowed with the capacity to prophesy (according to Paul, prophecy, not tongues, is to be the most sought-after spiritual gift) means that their words, their ability to speak on God's behalf, offers them an entryway into Church leadership. Many Christian communities, both historically and today, have made attempts to wrest that power away from women, viewing the prophetic role of women as secondary to the priestly role of men.

Finally, the spiritual gifts mentioned in this passage-prophesy and visions, and tangentially, dreams (never viewed as a spiritual gift per se, but definitely a supernatural occurrence that most Pentecostals would not deny exists)-have, historically, been some of the most controversial and unregulated experiences. Many heterodoxical expressions, misguided schisms, and tragic personal crises have begun with and been supported by individuals believing that they had received a prophetic word, either for the Church at large, or for one person. Because of the nature of Pentecostalism, questioning the trustworthiness of prophecy or visions has not been something Pentecostals have wanted to engage in, though it has not stopped them from viewing prophecy and visions outside their faith community to be aberrant.

Non-Pentecostal opinions on the claims to such experiences vary from merely skeptical to the starkly condemning. Pentecostals have engaged in a centuries-long dance on the edge of credulity, where other Christians admire their passion and claims to power as long as that power does not veer into the bizarre.

Historical Perspectives

Pentecostalism is a movement that has rarely been subjected to sustained critical analysis beyond decades-old arguments over origins and theological roots. In reviewing the historical literature on Pentecostalism from the beginnings in 1906, (or 1901 if one takes Parham as founder), one will find that there are no attempts to place the Pentecostal movement in any social, economic, cultural, or political context until the middle of the 20th century.

This does not mean that early Pentecostal history is unimportant. In fact, the contributions of amateur historian and Pentecostal evangelist Frank Bartleman are significant because these reports from Azusa Street have often been read as having the same gravity as scripture. Bartleman described the Azusa Street Mission as the "American Jerusalem." So impressed with what transpired, Bartleman's exercise in hyperbole fanned out to include such claims that because white people and people of color worshiped together at the Mission, "the color line had been washed away in the blood."

It may seem incredulous to many outside Pentecostalism, but that sentence in Bartleman's Azusa Street memoir seemed, for some, to paint the entire Azusa Street Mission as a racial utopia from which Pentecostalism stepped away over the course of the 20th century. If there is a "myth of Azusa Street," as historian Edith Blumhofer posits, Frank Bartleman is largely responsible for the mythic quality of the story behind William Seymour's church. So, one might wonder, why would anyone take Bartleman at his word? Why did it take Pentecostalism so long to produce scholarship that displayed the appropriate amount of scholarly analysis?

First-generation historians of Pentecostalism, largely religious insiders who were or sympathized with Pentecostals, had much to lose by being overly critical, and even more to lose if they suggested that not all of the events surrounding the origins of the movement and its theological roots were providentially inspired. To be fair, secular and non-Pentecostal scholars in the social sciences (chiefly sociology and anthropology) were not terribly interested in a movement that they knew little about and probably had little sympathy for. After all, if all one knew about Pentecostalism emanated from the popular press and from Hollywood (Elmer Gantry in particular), then the movement never really stood a chance in the less-than-receptive halls of academia. Suffice to say that Pentecostal historical scholarship in the first half of the 20th century suffered from bouts of intellectual lethargy from its biggest supporters and from ignorant disdain from its detractors.

Pentecostal scholarship would have to wait till the late 1960s and early 1970s for Pentecostal graduate students to finish their Ph.D.'s to uncover the varied histories that comprise Pentecostalism. Of note is Vinson Synan, a southerner affiliated with the Pentecostal Holiness Church, who attempted to move the discussion of Pentecostalism beyond the origins and theological roots arguments.

Synan contextualized Pentecostalism (with a heavy bias to southern groups) within the social and economic conditions that gave it some proto populist edges. Though other historians remained unconvinced by Synan's claims, he can be credited for attempting to place this movement outside of its sacred time constraints and addressing the influence of social location. Synan is also credited with insisting that William J. Seymour be considered the co-founder, along with Charles Parham, of Pentecostalism. Taking a more realistic tone than Bartleman, Synan enlarged the scope of inquiry about the racial dynamics that fed the Azusa Street experiment. He argued that, though nothing had been "washed away in the blood," clearly something was happening at Azusa Street if people of color and white people could worship together, effectively breaking the Jim Crow stronghold, if only for a brief moment.

Synan's sympathies are obvious, and others, particularly Robert Anderson, a non-Pentecostal historian, seemed to relish the lack of critical engagement by Pentecostal historians. Anderson he sought to fill that vacuum with the most systematic and controversial critique of Pentecostalism published thus far. Anderson's Vision of the Disinherited (1979) was the poke in the eye that had eluded Pentecostalism for decades. Pentecostalism, he argued, arose out of the social dislocation and feelings of lack of control in the lives of its adherents. Anderson wrote that the "radical social impulse inherent in the vision of the disinherited was transformed into social passivity, ecstatic escape, and finally, a most conservative conformity." Basically, who cares where Pentecostalism started? Who cares that it is Holiness or Pietist inspired? These people are simply responding to oppression and the fear that lack of control over their social location will eventually crush them, so they escape to the safe harbors of zealous experience, theological certainty, and social-political insularity. Nearly every history written since Anderson's has been, in one way or another, a retort or an expansion of his initial claims.

Biographies of Pentecostal leaders, chiefly James Goff's Fields White unto Harvest: Charles F. Parham and the Missionary Origins of Pentecostalism (1989), Daniel Epstein's Sister Aimee (1994), and more importantly Matthew Sutton's recent work (Aimee Semple McPherson and the Resurrection of Christian America (2007), have done much better at locating the leaders and Pentecostalism in general in the larger Christian stream and rigorously examining questions of gender inequality and social location.

Of late, issues of race have also been treated much more effectively in terms of critical analysis; biographies of Charles Parham have dealt with his support of white superiority much more forcefully than focusing exclusively on his theological innovation of the initial evidence doctrine or his alleged homosexuality. What has not been accomplished as yet is a synthesis of Pentecostal history that manages to effectively weave into these disparate analyses gender, race, and social location. Recent works by scholars have focused on Latino/a Pentecostalism, African American women, and attempts to cohere the disparate themes of race, ethnicity, and gender.