- Trending:

- Forgiveness

- |

- Resurrection

- |

- Joy

- |

- Afterlife

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Origins

Beginnings

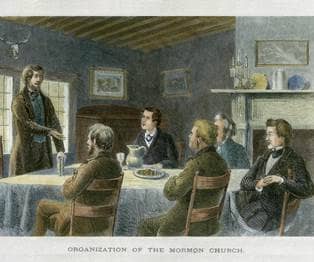

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormonism) came into being as an officially organized church in April 1830, when 24-year-old Joseph Smith and five others gathered in upstate New York to form what was initially called the Church of Christ. Emerging in an atmosphere of intense religious activity (later referred to as the Second Great Awakening), there was little indication at the time that the Church would eventually become the largest church to originate on American soil. Nor did Smith's fairly typical background and upbringing suggest he would become the most important innovator in American religious history.

Smith's paternal and maternal ancestors lived in a number of New England towns and participated in civic and religious life. His parents (Joseph Smith, Sr., and Lucy Mack Smith) married in 1796. Many years of hardship followed. After many attempts to settle in five different communities, the family moved, along with thousands of other poor farmers, to western New York in search of better soil and a brighter future. They arrived in the small village of Palmyra in 1816, with eight children. Joseph Jr. was ten years old.

Like many around them, the Smiths were Christians but did not feel compelled either to attend church with any frequency or to join a particular denomination. The move to New York distanced the family not only from its New England roots but also from its lingering Calvinist heritage. On moving to Palmyra, the Smiths found Presbyterian, Quaker, Baptist, and Methodist churches. Some family members were for a time associated with the Presbyterian church, while Joseph Jr. seemed interested in Methodism. But he found the array of Christian faiths and the heated disagreements between them confusing and troublesome.

Joseph's confusion over which church to join, and how to be saved, was intensified by the heightened emotional atmosphere characteristic of camp meetings and other features of the evangelical revivalism that washed over the region in waves. In 1820, at age 14, his prayer for guidance led to an experience that became the founding event of the Church and gave rise to his career as a prophet. In his accounts of this event, recorded many years later, Joseph wrote of being nearly overwhelmed by darkness, by which he had to muster all strength to call upon God in prayer, and then seeing a pillar of light encircling two beings, God the Father and Jesus. He was told that he was forgiven of his sins and that he was not to join any church, since none embodied the true faith; all had gone astray. As recorded in Joseph Smith History, one of the personages said to him, "They draw near to me with their lips, but their hearts are far from me."

This experience, later called the First Vision, was followed three years later by a more specific prophetic call. Again a divine messenger appeared. An angel named Moroni told Joseph about an ancient book, made of gold plates, that was buried in a hill near his home. The book contained a history of an ancient American civilization. Joseph was to retrieve the plates and translate them. He soon found the plates as described in the vision but was forbidden by Moroni from taking possession of them until 1827.

After being hired to dig for purportedly buried Spanish treasure in Pennsylvania, Joseph was arrested in 1826 for disorderly conduct, a charge that included telling the whereabouts of lost or stolen goods. While in Pennsylvania, Joseph also met and fell in love with Emma Hale. Although her father disapproved of Joseph, the couple eloped and were married in 1827.

The years from 1828 to 1830 marked an important period of transition for Joseph Smith. He found his prophetic voice and began to grow into his roles of church elder, prophet, and translator. Gradually, a distinct theology began to emerge, centering around the restoration of ancient beliefs, rituals, texts, and powers. Underpinning this theology was the core belief that God had spoken, and would continue to speak, through Joseph Smith and other designated leaders. Ongoing revelation thus formed the basis for all aspects of the new faith.

With Emma and Oliver Cowdery serving as scribes, Joseph dictated the text of The Book of Mormon, which was published in 1830. As a new American scripture, the book instantly set The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints apart from all other sects. It also contributed to the development of early Church doctrine. (The unofficial name "Mormons" derived from The Book of Mormon. In 1834, the official name was changed from Church of Christ to The Church of the Latter-day Saints, and in 1838 it was changed to the present name, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.)

Smith soon dispatched missionaries to spread the message that a new dispensation was at hand, that God had called a prophet as in ancient times, and that the fullness of the Christian gospel was contained in a new book of scripture. By the end of 1830, around a hundred individuals had been baptized in New York, and a similar number in Ohio. Converts were grouped into formal church units in three locations.

This formative period of the Church came to a close when a revelation directed church leaders to gather the entire body of converts in Kirtland, Ohio. By May 1831 nearly all members had left New York.

- When, where, and how did Mormonism originate?

- What was the role of Christian denominations in the creation of Mormonism?

- Who was Joseph Smith? Why was his status as a prophet important to the beginning of Mormonism?

- What was the First Vision?

Influences

As the 18th century came to a close, the prospects for American Christianity were less than encouraging. Memories of the Protestant revivals known as the First Great Awakening had long receded into memory, and the turmoil of the Revolutionary War era had taken a toll on religious life. Less than 10 percent of the population belonged to a church. This apparent state of decline, however, did not last long. The early decades of the new century brought a concentration of religious activity scarcely matched in any comparable period of world history. Now known as the Second Great Awakening, this period provides the general backdrop for the emergence of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Many different forces and circumstances coalesced to create an intense religious environment. Americans experienced social upheaval that affected every area of life. Disintegration of traditional structures and forms of authority fed into a spirit of opportunity, creativity, and competition. Established churches lost their privileged status and became like any other church or sect.

The sense of a new dawn, a new beginning, extended from the political to the religious sphere. It brought optimism and energy. Old hierarchies were replaced with populist, egalitarian visions of social life. Amid the turbulence of a society undergoing rapid, wrenching transformation, religion emerged as a potent force that both reflected and helped shape the wider social and intellectual currents.

One of the lasting developments during this period was the flourishing of an evangelical Protestantism that formed a united front. Competition coexisted with cooperation among the branches of Protestantism until the 1830s, when denominationalism asserted itself.

Central to the changing landscape of American Protestantism in the early 1800s was the voluntary association, a form of elective affiliation created for a certain purpose and, unlike earlier eras, not directed by the state or ecclesiastical authorities. Reform movements sprang up, addressing all sorts of social ills. Foreign and home missions, Sunday School, temperance, Sabbath-keeping, and prison reform are some of the causes taken up within the "benevolent empire" of Protestants. The cause of moral renewal merged the interests of churches with the needs of the new nation.

Theologically, too, the early decades of the 19th century were an unusually active, creative period. Notions of time and society were deeply impacted by a number of widespread theological currents. Many longed for a return to a primordial, distant past, and sought to implement this primitivism by recreating New Testament Christianity. Primitivism was often associated not only with the past, but the future as well, in the form of millennial expectations focusing on the imminent return of Christ.

Some religious groups reacted to the social disintegration by creating new forms of communal living. Others declared themselves independent seekers, dissatisfied with all existing claims to religious authority and truth. It was a time of visionaries and of self-declared prophets; many longed for a more powerful religious experience than was provided in the existing churches.

Many new religious groups sprang up in response to this spiritual longing. The spirit of revivalism stimulated a personal, emotional engagement with God. Although new groups often shared theological concepts with more mainstream churches, innovation could lead well beyond the acceptable boundaries of Christian orthodoxy.

Included among the many new groups to emerge under these circumstances were the "Mormons". Early Church history clearly reflects the social and religious milieu of western New York during the Second Great Awakening, an area known as the "burned-over district" for the intensity of religious activity. Joseph Smith's theology brought together a large number of ideas already in circulation. This was part of its appeal to converts near and far. Yet it was also a distinctly new creation.

Despite an abundance of contemporary records, the task of tracing the sources of LDS theology is a difficult one. There are several reasons for this. Among the Church's core beliefs are its claim to embody a "restored" Christian gospel, and its claim to continuing revelation. Both of these beliefs tend to obscure lines of demonstrable intellectual influence. Smith dictated revelations without explaining the underlying thought processes, if there were any. Nor did he ever write a carefully argued theological treatise. Moreover, Smith's lack of formal education or theological training makes it difficult to trace the impact of particular authors and writings he may have encountered.

It must also be borne in mind that in 1830, the year of its official organization, the early Church resembled evangelical religion much more closely than did decades later in 1844, the year of Smith's death. In 1830 Smith's theology was still in many ways compatible with the restorationist and millennialist streams of contemporary Protestantism. To that foundation was added, however, a second layer of restorationism, a distinctly Hebraic understanding of ritual authority and communal identity. A third layer was added in the final years of Smith's life, expanding the idea of restorationism into a more esoteric realm concerned with matters of afterlife and salvation.

- Why was the timing of the Second Great Awakening important to the formation of Mormonism?

- What reform movements were taking place at the time of Mormonism's origins? How did they shift the nation's consciousness?

- Why is it difficult to trace the sources of Mormonism's theology?

- What can be said about the relationship between evangelicalism and Mormonism (at its origin)?

Founders

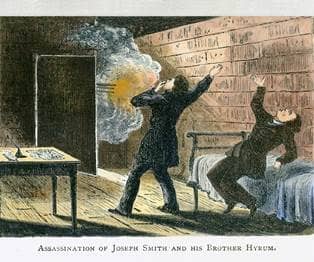

Joseph Smith, Jr. (1805-1844), a singular American religious figure who called himself a prophet and in 1830, amid the excitement of the Second Great Awakening, formally organized the Church of Christ (later changed to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints). He was murdered in 1844 by an anti-Mormon mob while imprisoned at Carthage, Illinois. His brother, and patriarch of the Church, Hyrum Smith, was also murdered.

Smith was born in Vermont in 1805 and in 1816 moved with his family to the town of Palmyra in western New York. Few details are known about his childhood. He showed little interest in reading while young, according to his mother, but seems to have been introspective. Joseph and his family briefly investigated Methodism but did not join any church at the time. In 1813, Joseph narrowly survived a bout with typhoid fever in which it infected the shin bone. Without antiseptic or anesthetic, Smith has part of his shin bone removed and made a miraculous recovery. Smith had no formal education and was regarded as being "proverbially good-natured" and "jovial."

Living in a place and time of evangelical revivals, the "burned-over district" of western New York in the early 1800s, Joseph became concerned about the state of his soul and the possibility of finding truth given the conflicting claims of rival denominations. According to his autobiography, penned many years later, he decided to heed the words of James 1:5 and pray to God for answers.

The result was a vision, around 1820, of God the Father and Jesus Christ, who, Smith wrote, instructed him to join none of the existing churches. Three years later Smith said he was visited by an angel named Moroni, who showed him a vision of buried gold plates that recorded an account of ancient America peoples.

In 1827 Joseph obtained the plates, along with several ancient objects buried alongside them, and set about translating them into English under divine inspiration. The record was published in 1830 as The Book of Mormon. Two sets of witnesses declared that they had seen the plates. Weeks after the new scripture was offered for sale, Joseph and his early followers convened to formally organize a church.

A year after the Church was formed, Joseph and his family moved to Kirtland, Ohio, along with about 200 converts. Kirtland would remain Church headquarters until 1838. The doctrine of gathering as Saints (i.e., followers of Christ) played a central role in LDS theology, combining notions of sacred time (belief in the imminent return of Christ and the establishment of his thousand-year reign) with notions of sacred space (the building of a ritual worship center called a temple).

New converts journeyed to Kirtland to join the Latter-day Saints. A distinct culture began to emerge as converts accepted The Book of Mormon and other doctrines and lived in a communal setting. The effort, however, failed dramatically when a financial crisis led to widespread dissent among Smith's followers. The high concentration of members(and their political power) had inspired mistrust among non-members, and soon Kirtland was no longer a safe haven.

Simultaneously with the gathering in Kirtland, another gathering place was designated in Independence, Missouri, where the Saints were directed to construct a city. Here, too, friction with settlers quickly escalated and in 1833 the Saints fled their homes, eventually settling in Caldwell, another Missouri county especially created for them by the state legislature. As converts continued to gather and swell the ranks of the Saints, that solution proved insufficient too. War broke out between the parties, and the Governor Boggs ordered the "Mormons" expelled or exterminated. The Missouri Executive Order 44 condemned the Saints for practicing their religions and called for direct military operations against the Saints. An article previously published to the Independence newspaper specifically mentions Missourians disapproved of the LDS inviting Black Americans to join the Church and suggested "an introduction of such a caste among us would corrupt our blacks, and instigate them to bloodshed." No evidence of early black American converts to the LDS Church would corroborate this claim. However, due to the increasingly hostile rhetoric and tensions from past conflicts, mobs formed and began to burn property and houses belonging to the Saints. W.W. Phelps' printing press, which published a Church newsletter was destroyed the same day the article was printed.

The Saints had to treat this threat seriously and fled to Illinois. Now refugees, the Mormons found a new gathering place, a swampy area along the Mississippi that Smith purchased and named Nauvoo (after the Hebrew word for beautiful, he claimed). In Nauvoo, Smith aimed to create a semi-independent Mormon kingdom where the Mormons could defend themselves against their persecutors. The city possessed its own militia and soon began construction of a temple. Conflation of temporal and spiritual affairs under Smith's expanding authority, however, along with rumors of polygamy, led to internal dissent and external opposition.

In 1844, Joseph and his brother Hyrum Smith were arrested and jailed, awaiting trial for an original charge of riot after mustering the Nauvoo Legion, a militia, to protect the Saints from harm. Joseph Smith said, before heading to Carthage jail, "I am going like a lamb to the slaughter; but I am calm as a summer's morning; I have a conscience void of offense towards God, and towards all men. I shall die innocent, and it shall yet be said of me -- he was murdered in cold blood."

Joseph and Hyrum were both shot and killed by a mob. Smith's death was followed by a period of uncertainty, as over two dozen men claimed the authority to assume Church leadership. The struggle was won by Brigham Young (1801-1877), who became the second president of the Church. With prospects in Illinois increasingly dim, Young led the Saints across the plains to the Salt Lake Valley, arriving there in 1847.

- Why could it be argued that Joseph Smith's childhood was influential for his founding of Mormonism?

- Why did Smith consider himself to be a prophet?

- What is The Book of Mormon? How was it inspired?

- Why did the geographical headquarters of Mormonism change over time?

Sacred Texts

The concept of scripture is central to LDS history and theology. It is one of the pivotal areas of differentiation and contestation between members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and other groups. The basic definition of scripture within Church canon is that which is spoken or written when moved upon by the Holy Ghost. In conjunction with the Mormon belief in continual revelation, this broad definition of scripture leads to the principle of an open canon; scripture is never final or complete as God continues to speak to living Prophets and Apostles like He did during the early Church.

At the same time, however, the corpus of authoritative writings rests on a relatively fixed set of four books: the Bible (a Church-produced King James Version with Mormon annotations is the preferred version), The Book of Mormon, The Doctrine and Covenants, and The Pearl of Great Price. Generally speaking, Mormons understand scripture as encompassing these four "standard works" as well as official pronouncements and sermons by general authorities of the Church.

The idea of an "open canon," then, refers mainly to the belief that Church leaders receive divine inspiration and that their utterances are considered equal in authority to existing canonized texts. It also implies that scripture is an expansive, open-ended category that always exceeds known, existing texts. In practice, Mormon history has received far more scholarly attention than Mormon texts. There are many issues surrounding the composition and usage of Mormon scripture that have not been adequately addressed. Regardless, the Church sees the Book of Mormon, D&C, and The Pearl of Great Price as complementary scriptures that add to, clarify, and build upon the principles of the Gospel of Jesus Christ found in The Holy Bible. The entire cannon helps readers come unto Christ and be perfected in Him.

The Book of Mormon

The Book of Mormon gave Mormons their unofficial name and set them apart as a distinct religious community. Joseph Smith and a number of witnesses reported that Smith translated the book from a set of gold plates that he found in a hill near his home in Palmyra, New York. The translation proceeded by inspiration. Smith did not know the language on the plates, referred to in the text as "reformed Egyptian." The book was published in 1830 and made Smith a minor national figure. Smith claimed that he returned the plates to the angel Moroni when the translation was complete.

The central narrative of The Book of Mormon is the story of Lehi and his family, who fled Jerusalem around 600 B.C.E. and travelled across Arabia before constructing a boat and sailing to a promised land. The bulk of the book tells of the family's struggles in their new environment (which traditionally has been understood as America) as they went through cycles of war and peace, wealth and poverty. Lehi's descendants formed two opposing groups, Nephites and Lamanites, who were often at war with one another. The climax of the narrative involves a visit from the resurrected Christ to Lehi's descendants.

The Book of Mormon has always been a heavily contested text, and from the beginning many have embraced or discarded it without having read it. Thus it has always had a strong iconic function, viewed as representing either Smith's prophetic gifts and divine calling or his madness and fraudulence. Modern Church leaders have sustained the Book of Mormon and its role as "Another Testament of Jesus Christ." In 2009, Jeffrey R. Holland, an Apostle, gave his testimony of the Book of Mormon and its role in Christian theology while defending the claims made by Joseph Smith, "Never mind that their wives are about to be widows and their children fatherless. Never mind that their little band of followers will yet be 'houseless, friendless and homeless' and that their children will leave footprints of blood across frozen rivers and an untamed prairie floor. Never mind that legions will die and other legions live declaring in the four quarters of this earth that they know the Book of Mormon and the Church which espouses it to be true. Disregard all of that, and tell me whether in this hour of death these two men would enter the presence of their Eternal Judge quoting from and finding solace in a book which, if not the very word of God, would brand them as imposters and charlatans until the end of time? They would not do that! They were willing to die rather than deny the divine origin and the eternal truthfulness of the Book of Mormon."

The Doctrine and Covenants

The first version of the second canonical text, The Doctrine and Covenants, was published in 1833 as A Book of Commandments and contained sixty-five revelations received through 1831. The utterances address day-to-day business matters within the nascent sect as well as more abstract matters of Church doctrine. The revelations were arranged chronologically, without commentary. Smith seems to have been more concerned with obtaining directions suitable for the moment rather than ensuring theological clarity or consistency.

In 1835 a further compilation of revelations was published with the title of The Doctrine and Covenants. It was presented to the Church members for acceptance and thus officially canonized. Since then, additions to the revelations to Joseph Smith and his successors, the presidents of the Church, have resulted in steadily expanding compilations under the same title.

The Pearl of Great Price

The Pearl of Great Price, by far the shortest of the four canonical works, brings together "Selections from the Book of Moses," "The Book of Abraham," "Joseph Smith-Matthew," "Joseph Smith-History," and "The Articles of Faith." It was first published in Liverpool in 1851 in response to requests from new converts and later adopted officially.

The section on Moses consists of inspired expansions of the Old Testament account of Moses, while the Abraham text likewise fills out existing narratives from the lives of the patriarchs. The latter has for many years been a point of controversy, the major issue at stake being the relationship between Smith's translation and Egyptian scrolls found inside several Egyptian mummies purchased by Smith in the 1830s. The question is not likely to be resolved.

The Bible

The fourth work of Mormon scripture is the Bible, which played a crucial role in the creation of the other three texts in the canon. Smith had a much more open conception of the Bible than his contemporaries and viewed his prophetic authority as license to revise the Old and New Testaments.

In producing additional scripture, and using the biblical narrative as a point of departure, Smith reinforced biblical authority while also revising long-established translations of previous versions of the Bible. He placed himself inside the biblical narrative, forming a human link between diverse scriptural texts. He combined literal with metaphorical interpretations. He also resisted the idea of a revelation or scriptural text ever being in a final, unalterable linguistic form that would close the canon.

- How do Mormons define scripture? Why is it an open canon?

- What are the four books most utilized by Mormons? Describe each of their central teachings.

- What is the central narrative to The Book of Mormon? Why is the book contested?

- How did Smith understand biblical authority?

Historical Perspectives

"Mormonism" has been the subject of intense interest to a wide range of writers from the organization of the Church in 1830 until the present. The vast majority of historical and contemporary commentary on The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints may be divided into two main camps, apologists and critics, with a third, much smaller contingent of more objective individuals in the middle. As early as the 1830s, for example, Alexander Campbell, a major figure in antebellum American religious life, published an analysis of The Book of Mormon. Campbell argued that The Book of Mormon represented a transparent attempt on the part of Joseph Smith to resolve all of the contentious issues circulating in the American Christian community in the early 19th century by an appeal to a fictitious ancient scripture that Smith fabricated. At the same time, Mormon thinkers attempted to offer as evidence for the antiquity of the book the narrative's sophistication and Smith's apparent inability to have conceived of and produced such a work.

The themes that informed these writings in the 1830s persist into the present. Much of the historical material on Mormonism is colored by the so-called "prophet/fraud" dichotomy. Joseph Smith's claims to divine revelation and prophetic gifts were seen as either genuine religious experiences or as conscious frauds invented by Smith and foisted on his naïve followers. The side of this dichotomy taken by a given writer would necessarily shape that person's interpretation of the whole of Mormon history.

Although this remains the dominant template for the writing of Mormon history even today, some notable efforts to move beyond the dichotomy have been made. While most Mormons consider Fawn M. Brodie's biography of Joseph Smith to be a vicious attack on the Mormon prophet, her work actually displays a relatively sophisticated approach. Published in 1945, Brodie's No Man Knows My History was the work of a disaffected Mormon, the daughter of a general authority and the niece of Church President David O. McKay. Joseph Smith, she argued, was a Huckleberry Finn-like character, who began to claim prophetic gifts as a lark but who eventually came to believe in his own gifts. Brodie, while not the first biographer to take a psychological measure of Smith, popularized the notion that The Book of Mormon may best be understood as a veiled map of Smith's own deepest desires and fears, played out allegorically in an adventure story set in the New World and couched in the Jacobean English that Smith recognized as scriptural language.

Brodie's book was immensely popular, and remains in print today. Believers naturally take issue with the book's premise and Brodie's clear disdain for Smith leaves Mormons cold. Nevertheless, the book appealed to non-Mormons who rejected Smith's prophetic claims, but who, like Brodie, recognized the remarkable achievements that he was able to reach in his short lifetime. She was excommunicated from the Church for "apostasy" but her work remained the premier biography of Joseph Smith until the 2005 publication of Richard L. Bushman's Rough Stone Rolling.

Bushman's book is written by a believer for believers, but he makes no effort to cast Joseph Smith in an unblemished light. Rather, Bushman approaches such controversial issues as Smith's polygyny and polyandry, by attempting to contextualize and explain Smith's motives in a way that modern Mormons will find acceptable.

The sixty years between Brodie's book and Bushman's work saw some progress in Mormon historiography. During the 1960s and 1970s there arose a movement of "New Mormon History" in which Mormon and non-Mormon scholars attempted to approach their subjects through a stance of functional objectivity. By bracketing questions of ultimate concern, these scholars sought to obviate the prophet/fraud dichotomy, and all of its resulting scholarly segregation. Mormons, such as Leonard Arrington and Thomas Alexander, and non-Mormons, such as Jan Shipps and Lawrence Foster, made common cause of Mormon history and produced high-quality work that avoided the agendas of apologists and critics.

Today, the New Mormon History has come under criticism for relying too heavily on a phenomenological approach that stressed recitation rather than interpretation. Although this is certainly not true of the best work produced by these scholars, it is a viable critique of much of the less compelling work. In any case, the decline of the New Mormon History has coincided with a resurgence of strong apologetic and critical voices on either side of the Mormon/non-Mormon divide. The increasing cultural power of conservative Evangelical Christians, many of whom view Mormonism as a dangerous anti-Christian "cult," has led to a plethora of books and websites designed to expose the truth about Mormonism and win Mormons over to Christ. On the other side, vigorous Mormon apologetic organizations such as the Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies (FARMS) have taken on the task of responding to criticisms of the Mormon Church through their own print and internet publications. In addition, FARMS, which currently exists as part of Brigham Young University, seeks to provide historical and archaeological evidence for The Book of Mormon.

Scholarly approaches to the LDS Church have also been influenced by the resurgence of critical and apologetic debates, and many scholars no longer seek to employ the phenomenological models of functional objectivity popular with the New Mormon historians. John L. Brookes's award-winning 1994 history of early Mormonism entitled The Refiner's Fire accepted as fact Joseph Smith's invention of revelatory experiences and highlighted Smith's heavy borrowing of hermetic and Swedenborgian modes of thought and ritual in the construction of Mormonism. In 2000, Mormon scholar Teryl Givens published By the Hand of Mormon, a literary and historical look at The Book of Mormon that focused on its role in early Mormon thought as well as the contentious debates that the book has spurred in recent years. While Givens presents his work as an open airing of criticisms and the response offered to them by FARMS and other apologetic groups, Givens clearly favors the FARMS arguments, and offers them up without the same vigorous critique to which he subjects the work of anti-Mormon authors. Both books were published by prestigious presses (Cambridge and Oxford respectively), which suggests that a new era of sectarian warfare may be afoot in the scholarly arena.

Although it is possible that cooler heads may eventually prevail and relegate the boisterous insider/outsider debates to the scholarly margins, the success of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and the persistent presence of Mormons in prominent political, economic, cultural, and ecclesiastical roles will tend to encourage partisan wrangling in the interpretation of the religion's past and resist less polarized modes of historical discourse.

- What are the three camps of historical commentary on Mormonism? What does each believe?

- Explain the prophet/fraud dichotomy.

- What did Fawn M. Brodie write that has created a controversy within the Mormon church? Why is the book still popular today?

- How have scholars created debate about Mormonism?