- Trending:

- Olympics

- |

- Forgiveness

- |

- Resurrection

- |

- Joy

- |

- Afterlife

- |

- Trump

RELIGION LIBRARY

Christianity

Schisms and Sects

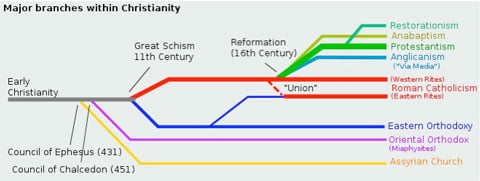

When the Visigoths (an invading Germanic tribe) sacked Rome in 410, Christian communities could be found as far west as the British Isles, south to North Africa and Ethiopia, north to the Danube and modern-day Romania, and east from modern-day Turkey into Armenia and perhaps even India. Geographical distance and political and cultural differences gave rise to two powerful and competing seats of power, the pope in Rome and the patriarch in Constantinople. The Latin-speaking western Church referred to itself as the universal or Catholic Church. While the Greek-speaking eastern Church also affirmed the Church's universality, it developed an equally firm understanding of the pure and unchanging nature of its doctrine. Thus it became known as Orthodox, meaning "correct worship," including the sense of "correct belief."

| Filioque Clause | |

| LATIN | ENGLISH |

| Et in Spiritum Sanctum, Dominum, et vivificantem: qui ex Patre Filioque procedit. | And in the Holy Spirit, the Lord, and giver of life, who proceeds from the Father and the Son. |

Over the centuries, the two churches were involved in power struggles between the Byzantine Emperor, the Roman pope, the patriarch of Constantinople, and the various rulers and warlords of the peoples and nations of northern and central Europe. Nevertheless, the split between the churches of the East and West was not abrupt, but a result of a slow breakdown in understanding and solidarity. In the 6th century, the western Church had slightly modified the Nicene Creed in order to clarify the doctrine of the Trinity (the filioque clause), but the eastern Church was not involved in this revision, did not add the same language to the Creed, and protested the western Church's unilateral action.  In the 8th and 9th centuries, the entire Church was deeply upset by a serious controversy over the use of icons in the Byzantine Church. Finally, when Pope Leo III crowned Charlemagne, king of the Franks, the Holy Roman Emperor in 800, the eastern Church perceived this as an apparent challenge to the authority of the Emperor in Constantinople. The two branches of the Christian church grew increasingly distant.

In the 8th and 9th centuries, the entire Church was deeply upset by a serious controversy over the use of icons in the Byzantine Church. Finally, when Pope Leo III crowned Charlemagne, king of the Franks, the Holy Roman Emperor in 800, the eastern Church perceived this as an apparent challenge to the authority of the Emperor in Constantinople. The two branches of the Christian church grew increasingly distant.

The two churches also developed different positions on a variety of leadership issues. The western Church discouraged marriage of priests and bishops, while the eastern Church allowed it. The western Church insisted that the pope was the first among bishops and the supreme authority, while the eastern Church encouraged more autonomy for local churches and their leaders, including the patriarch at Constantinople, and attributed supreme authority to the councils of bishops.

Ultimately, what came to be referred to as "the Great Schism" divided Latin Roman Christianity (in the West) from Greek Byzantine Christianity (in the East). The formal or official schism of 1054 resulted not from one specific event or argument, but from powerful differences in geography, culture, politics, and Christian doctrine. The geographical, linguistic, and theological distances between the two churches, their different ways of worshipping, and their different styles of internal organization and authority, resulted in two very different churches.

Ultimately, what came to be referred to as "the Great Schism" divided Latin Roman Christianity (in the West) from Greek Byzantine Christianity (in the East). The formal or official schism of 1054 resulted not from one specific event or argument, but from powerful differences in geography, culture, politics, and Christian doctrine. The geographical, linguistic, and theological distances between the two churches, their different ways of worshipping, and their different styles of internal organization and authority, resulted in two very different churches.

At the local and regional level, there was varying awareness of these differences, but the Crusades made the differences apparent on all levels. In March of 1095, Pope Urban II, with ambassadors from Constantinople at his side, made a passionate appeal for Christian soldiers to help free formerly Christian lands from Muslim rule.  This invocation launched the first crusade. Pope Urban II was able to maintain harmonious relations between the Christian soldiers from the west and the Christians of the east. But after Urban's death in 1099, bishops from the western tradition were appointed to the traditionally eastern patriarchates of Jerusalem and Antioch. The introduction of western-style worship and hierarchy made the differences between the two churches immediately visible. The differences were made more painfully clear in 1204, when Christian soldiers sent from Rome to Egypt diverted to Constantinople, sacking it and driving the Byzantines into exile.

This invocation launched the first crusade. Pope Urban II was able to maintain harmonious relations between the Christian soldiers from the west and the Christians of the east. But after Urban's death in 1099, bishops from the western tradition were appointed to the traditionally eastern patriarchates of Jerusalem and Antioch. The introduction of western-style worship and hierarchy made the differences between the two churches immediately visible. The differences were made more painfully clear in 1204, when Christian soldiers sent from Rome to Egypt diverted to Constantinople, sacking it and driving the Byzantines into exile.

Efforts to heal the schism and reunify the two churches continued throughout the 13th and 14th centuries, but when the Ottomans, led by Muhammad II, conquered Constantinople in 1453 and renamed the city Istanbul, all possibility of reunion was lost. From this point forward, Christianity would be divided into an eastern Church and a western Church.

Less than a century passed before a teacher and monk named Martin Luther famously nailed his list of ninety-five propositions or "theses" to the castle-church door at Wittenberg in Saxony in 1517. Luther's list addressed Church practices and the nature of faith. Luther believed passionately that truth should be sought in scripture, and that Church teaching is to be based on and accountable to scripture. His ideas echoed those of Jan Hus and John of Wycliffe, two 14th-century theologians who protested Church corruption and the abuse of authority.

Less than a century passed before a teacher and monk named Martin Luther famously nailed his list of ninety-five propositions or "theses" to the castle-church door at Wittenberg in Saxony in 1517. Luther's list addressed Church practices and the nature of faith. Luther believed passionately that truth should be sought in scripture, and that Church teaching is to be based on and accountable to scripture. His ideas echoed those of Jan Hus and John of Wycliffe, two 14th-century theologians who protested Church corruption and the abuse of authority.  Moreover, Wycliffe wrote that Christians need nothing more than the example of scripture, and that they should be able to read the Bible in their own languages.

Moreover, Wycliffe wrote that Christians need nothing more than the example of scripture, and that they should be able to read the Bible in their own languages.

Although Luther intended his propositions as an invitation to debate within the Church, the theses prompted the second great split in Christianity, the Protestant Reformation. Luther acted at a time when the recently-invented printing press made it possible to reprint his theses. In six short years, 1300 copies were printed. The widespread dissemination of Luther's ideas made it difficult for the Church to simply reprimand him and sweep the problem under the carpet. Northern Europeans and their leaders, weary of Church corruption and yearning for independence from Rome, embraced Luther's criticisms. An airing of controversial tenets on a church door culminated in catastrophic violence and persecution, and a permanent splintering of the western Church.

Although Luther intended his propositions as an invitation to debate within the Church, the theses prompted the second great split in Christianity, the Protestant Reformation. Luther acted at a time when the recently-invented printing press made it possible to reprint his theses. In six short years, 1300 copies were printed. The widespread dissemination of Luther's ideas made it difficult for the Church to simply reprimand him and sweep the problem under the carpet. Northern Europeans and their leaders, weary of Church corruption and yearning for independence from Rome, embraced Luther's criticisms. An airing of controversial tenets on a church door culminated in catastrophic violence and persecution, and a permanent splintering of the western Church.

Reformation ideas infiltrated England, and in 1533, King Henry VIII severed the English Church from Rome's authority, thus creating the Church of England. In 1555, the Treaty of Augsburg created Lutheranism, permanently breaking this group away from Roman authority. More schisms followed. Huldreich Zwingli, the Anabaptists, and John Calvin all led reformation movements in Switzerland. Calvinists in England were known as the Puritans, proclaiming their desire to purify the Church of any reminders of Roman Catholicism.

Reformation ideas infiltrated England, and in 1533, King Henry VIII severed the English Church from Rome's authority, thus creating the Church of England. In 1555, the Treaty of Augsburg created Lutheranism, permanently breaking this group away from Roman authority. More schisms followed. Huldreich Zwingli, the Anabaptists, and John Calvin all led reformation movements in Switzerland. Calvinists in England were known as the Puritans, proclaiming their desire to purify the Church of any reminders of Roman Catholicism.

In response to this tide of schisms, the Catholic Church tacitly accepted Protestant criticisms of corruption and undertook its own reformation. It initiated steps to bring increased integrity and accountability to seminaries, dioceses, and monasteries. Christianity emerged from the paroxysm of reformation ready to take great strides in mission, global exploration, and conquest.

Study Questions:

1. Was the earliest split of Christianity more about location or language? Explain.

2. What was the Great Schism? What was the result?

3. How did the crusades contribute to schisms of Christianity?

4. Who was Martin Luther? What movement did he found and why?