Beloved, we have existed within you for all of our days.

Before the earth was formed and the mountains arose, before stars and dreams, before any beginnings and all the endings, it is holy. You are holy. Even in the midst of our worst, you are there. And always you whisper a call to return.

A thousand years for you are no more than yesterday, like a watch in the night. You are found in the rising flood, and in the growing grass. And in our dreams.

We are like the grass growing in the morning which is cut down in the evening. We are consumed in the play of the cosmos, indifferent to our joy and pain, and so often we miss the harmony of the worlds.

Our secret sins, our separation from the world and you brings consequences. And our years are as a tale that has been told. We live seventy years, or if we are strong, eighty. But strength and sorrow, it is quickly cut away, and we fly into our many parts.

Who knows the power of the cosmos and the consequences of our choices?

So, Beloved, teach us the way, teach us to notice our passing days, and turn our hearts to wisdom. Meet us in our struggles, satisfy us with mercy. Allow us to rejoice and be glad all of our days.

Make us to find our way into the flow of causes and conditions, let the way of harmony open for us, and let us come into your glory.

As your children, let the beauty of the heaven be upon us and establish in our hands the work of the holy.

Psalm 90 (my paraphrase)

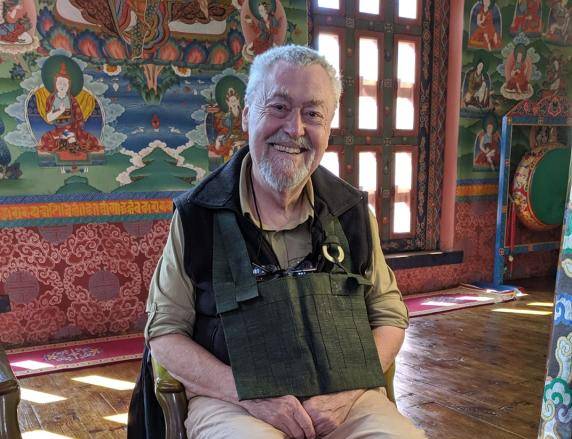

I was born in Oakland, California, on the 17th of July 1948.

Seventy-five.

Three quarters of a century.

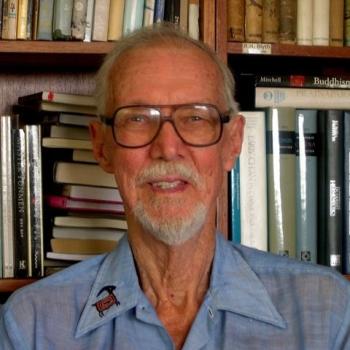

The author of the 90th Psalm puts human life at seventy, unless strong, unless lucky, and then eighty. Tradition, and the text, credits Moses with authorship. Scholars tend to place it to the fifth century before our common era, parts likely a fair bit older. At the very least it was written some twenty-five hundred years ago.

I’m intrigued that our American Social Security actuarial tables give me the odds of living another decade and change. A bonus five years over antiquity, at least if one wasn’t a slave or poor. Although this guesstimate is calculated with that additional factor of my being seventy-five accounted for. This year an American woman’s odds at birth, factoring only gender and being an American is eighty-one and change, while an American man’s is seventy-six and change. So, few real changes at all. The big difference I think is tose outer numbers attach to more people. Which is good. It strongly looks like anyone who lives longer, dipping past a hundred, has one feature going in common with that cohort, their parents were also extremely long-lived.

As to me. I’m overweight, prone to back spasms, and my doctors have me taking ten pills a day, a couple of them pretty strong medicine. Otherwise, I’m in relatively good shape. Unless something is unfolding deep within my body that I’m unaware of, I kind of think I might make that additional decade.

It’s all been interesting. Which some say is a curse. And there have been some very hard times. But, well, some astonishing moments of joy and clarity, as well. As they say, on the one hand, it’s been one long weird trip. And, on another, I swear, it’s been the blink of an eye.

And. Well. Among the things I’ve learned in my seventy-five years is that one shouldn’t assume much of anything. Death, it can come like that proverbial thief in the night. And whatever else, it will come. The price of our birth is our death. Another little lesson I’ve picked up in the gutters and alleyways of life.

For a detailed account of my life, I wrote this in 2015. In that year when Jan retired as a librarian I retired as a parish minister, and we moved back to the Los Angeles area in order to be close to Jan’s mom. We bought a condo in Long Beach. Eight years now since we relocated from Providence. And Jan’s mom’s world began to shrink. As of some months ago for all practical purposes we’ve moved in with her in the Tujunga neighborhood of LA.

And here we are. Jan and me. At seventy-five living with my mother-in-law. We are not sure what’s next. We’re reluctant to sell the condo, and putting off any such decision for a while.

That said, here we are.

Do I have any words of wisdom to celebrate the day? People are sometimes asked that question. I recall how Aldous Huxley lamenting all he could offer in his old age was the advice to be a little kinder. Not bad. Not bad, at all. And, if only…

At the heart of the matter as I’ve found it is some strange and wondrous thing that human beings can experience. Or encounter. Something. The words fail as we approach it. I’ve pursed it. It has pursued me. And, in that thing I have what little wisdom I have to share.

I’ve struggled with how best to define this, well, let’s say thing.

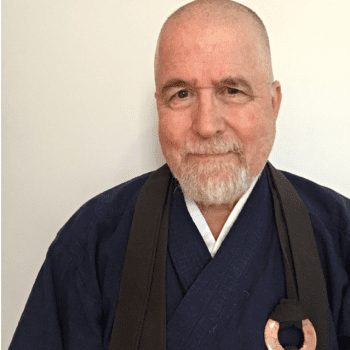

Alan Watts was a big deal in my youth and young adulthood. His romantic interpretation of Zen was a large part of why I began to practice. He had more than a few problems, and soon after I took up Zen in more traditional ways, I stopped reading him. (I should note today I consider him more important in my life as a bridge between my Zen and my natal Christianity.)

These days when I think about this thing, this most important thing, I find myself returning to something in wrote in one of his books that I did read, the Book on the Taboo Against Knowing Who You Are.

As he described it and as I see it the universe is God. God is the universe. There is no part of the universe that is not divine. But there is a mystery of part and whole. Each part, each star and planet, and each and everything on the planets are God’s dreams. Some of the dreams are pleasant and some are not. But they’re all God.

Alan Watts takes this pantheistic view of God and the universe and elaborates.

“(R)emember that God isn’t shaped like a person. People have skins and there is always something outside our skins. If there weren’t, we wouldn’t know the difference between what is inside and outside our bodies. But God has no skin and no shape because there isn’t any outside to him. The inside and outside of God are the same….

“God is the Self of the world, but you can’t see God for the same reason that, without a mirror, you can’t see your own eyes, and you certainly can’t bite your own teeth or look inside your head. Your self is that cleverly hidden because it is God hiding.”

Then Watts suggests the whole play of the universe is God playing hide-and-seek. He goes on to make an argument that bad things happen for the drama of it. I think his narrative begins to fall apart there. So, from there we might find more a more useful of God image in the Bhagavad Gita in chapter 18:

“That knowledge by which one undivided spiritual nature is seen in all living entities, though they are divided into innumerable forms, you should understand to be in the mode of goodness.”

I find it a pretty good shorthand for the thing we can find as we look deeply into the matter of who we are within this passing strange universe, this isn’t a bad image.

Another pointer can be found in the shorthand of the Zen way found in the Heart Sutra: form is emptiness, emptiness is form. Instead of empty, we might say boundless. If we take a pantheistic stance, boundless is God. The no-thing, the every-thing of which we are made, within which we exist, and to which we return. In every single moment of our existence. I don’t see God as a being who is in any way like a human. But, rather a very good symbol or sign for the majesty of it all, and for how we as human beings often encounter it. The language of religion feels right to me. Holy. Sacred. Whirlwind. Storm. Still small voice. God.

And there’s something else we can miss in taking a simple materialistic view. In this knowing we are not limited to our seventy or eighty years. There are genuine ways in which we are immortal. Or, at least we exist fully within the play of time and space. Both separate and mortal and connected and eternal. Again the language of heart of poetry of religion feels most right.

So, a take away? Some small words that approximate wisdom for my seventy-fifth birthday?

It may all be a game from some perspective. But its real for you and me. There’s a ton of suffering out there. And those of us who got pretty good hands in the current shuffle, I believe we have some obligations. Which is something I don’t think the good Mr Watts ever actually got, but which we find pushed to its logical conclusions in the Gita. And, while I deeply believe in our mutual responsibility, I draw short of the version called for in the Gita. Duty, yes. Duty forms a significant part of my life. But we also can make choices, as well. And our fate isn’t completely written in the stars. With that I think Aldous Huxley got it best, try to be a little kinder to each other.

This thing about being one thing, you and me and the universe, I do like calling that whole of it all, God. For us as human beings it’s all holy. This is the task I suggest is as close as we’re going to get to meaning and purpose: Knowing who we really are for ourselves, giving eyes and hands back to God. Living in the dance.

The project of our ending suffering is twofold. The first is our intimate encounter, that awakening thing. The second is real-world. Helping. In various ways, being of use. Of discovering the duty that comes with our birth, the things we need do between birth and death.

From dark to dark. The light inside the dark. The dark inside the light. Bleeding through the cracks in the heart of the universe. Those cracks in your heart. And mine…

Okay, I’m running on here.

But that’s it in a nutshell. What I have to offer after seventy-five years.

Please, look for yourself for the saving moment, your deepest awakening into the mystery.

Please, try to be a little kinder to each other.