- Trending:

- Olympics

- |

- Forgiveness

- |

- Resurrection

- |

- Joy

- |

- Afterlife

- |

- Trump

The 100 Most Holy Places On Earth

Sulayman Mountain

Associated Faiths:

Islamic

Also frequently visited by those of other religious traditions—particularly Christianity

Accessibility:

Open to visitors.

Number of Visitors: There are no official numbers available regarding the annual number of visitors to this site.

History

For more than 1,500 years, the peaks of Sulaiman-Too have been revered as sacred, for Muslims and pre-Muslims alike. Indeed, the ancient petroglyphs on the walls of Suliman-Too’s various caves suggest that, as early as 500 BCE, people believed there was something holy about this place. At the crossroads of the ancient “Silk Road,” merchants and travelers would have frequently passed this way in antiquity. Because Sulayman Rock was associated with miracles, pilgrims and peddlers would stop in the hope of health, luck, and prosperity.

Because of the abrupt way in which the Sulayman Rock rises from the otherwise baren appearing plains of the Fergana Valley, the Sulayman Mountain appears a bit like an ancient temple (mountains so often being uses as such in ancient times). It was on such a structure that Moses received of God’s law and the Prophet Muhammed first encountered the Angel Gabriel. Named after the Qur’an’s Sulieman (or Solomon), on this sacred site is a grave purported to be that of the ancient biblical king—himself a builder of a temple. (The name “Suliman-Too” means “Solomon’s crown.”)

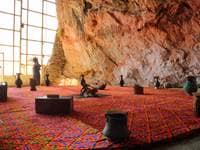

The peaks and slopes of this rocky backdrop to the city of Osh contain various sites that were once places of worship. Small mosques, sacred caves, stone shrines—all of these attests to the draw this location has had for millennia. The home of some seventeen spots currently used for worship, and many places of the past which are no longer utilized, the Sacred Mountain has a history of healings—from curing barrenness to relieving backaches, and from healing headaches to lengthening life. Some of the most important and venerated sites on the “mountain” include the remains a medieval bath (believed to have been used between 11th-14th centuries), the 16th century Takht-i Suleiman Mosque (atop of the mount), the Rawat-Abdullakhan Mosque (also from the 16th century), and the 18th century mausoleum of Āṣif bin Barkhiyā—referenced in the 27th Surah of the Holy Qur’an. While the site is littered with caves, there are “seven sacred caves” which can be visited, displaying many ancient petroglyphs.

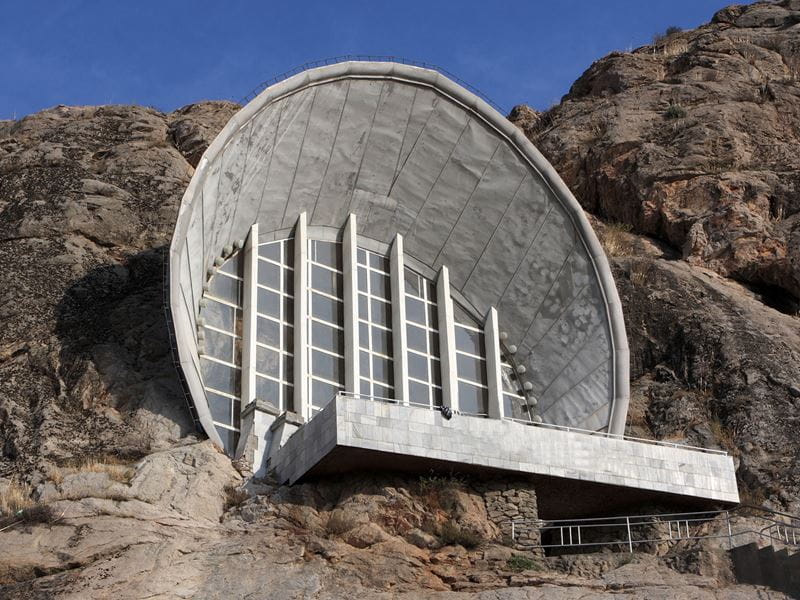

Sadly, though the “mountain”—which is more of a foothill at approximately 600 feet in elevation—has been a natural temple for the last 2,500 years, or so, the former Soviet Union added an eyesore of a museum to its side. Built into one of Sulaiman-Too’s natural caves, this 20th century for-profit museum is an unpleasant site that ruins the natural beauty of the peak on which it has been built. Boasting 33,000 exhibits, though very little of its information is in English, it is a perfect example of how the profane too often encroaches on the sacred.

Religious Significance

Ancient mountains were one of the primary places one went in order to get closer to God. The concept of the “sacred mountain” is common in many ancient traditions. Mount Sanai (in Judaism), Mount Kailash (in Hinduism), and even Mount Olympus (in Greek Mythology)—each of these stands as a testament to the doctrine of the “sacred mountain” and its widespread acceptance in cultures and religions of antiquity. Atop a mountain peak, one was perceivably closer to the divine, or to the divine realms. One was removed from the world and, thus, removed from the temptations which kept one from communion with the higher power. The numerous current and ancient worship sites which litter the top and slope of Sulaiman-Too serve to prove that for millennia many have understood this to be a “sacred site.”

Sometimes referred to as “Sulayman Throne,” near its top is a shrine to King Solmon (or Soliman). It supposedly marks the exact location of his grave. Thus, the spot has a connection to all three of the Abrahamic traditions—each of which have a place of reverence for the ancient king. As a prophetic figure in Islam, the builder of the first Israelite Temple (in Judaism), and the source of the Book of Proverbs (so popular in Christianity), Solomon’s grave is understandably purposeful for pilgrimage.

We know that, for at least 1,500 years, people have come here seeking healing from various maladies.

For example, located atop Suliman-Too is the “holy rock,” with a small opening in it. According to tradition, it is said to promote fertility. Thus, if a woman will hike to the top of the Sacred Mountain and pass through the opening of the “holy rock,” she will become pregnant and give birth to healthy children. Similarly, located on the slope of Sulayman Mountain is a slide naturally appearing in the rock that, so it is claimed, if you slide down it, your back pains will be cured. There are crevices at various places on the mount, which are said to have the power to heal certain body parts—the head (or headaches), the arms, the legs, various body aches and joint pains. Much like other famous sites of healing throughout the world, there is no proof that these work, but there are certainly the testaments of those who have been healed. Thus, like Lourdes in France, people come here to be healed, and many leave better than when they came.Though this may be one of the least known places of pilgrimage, and perhaps one of the least visited, it is the most important one in the county of Kyrgyzstan. Indeed, it is the only site in that entire country that has made UNESCO’s World Heritage List. And for 2,500 years before UNESCO even noticed it, pilgrims found faith and healing, divine comfort and communion, at Suliman-Too, the Sacred Mountain.