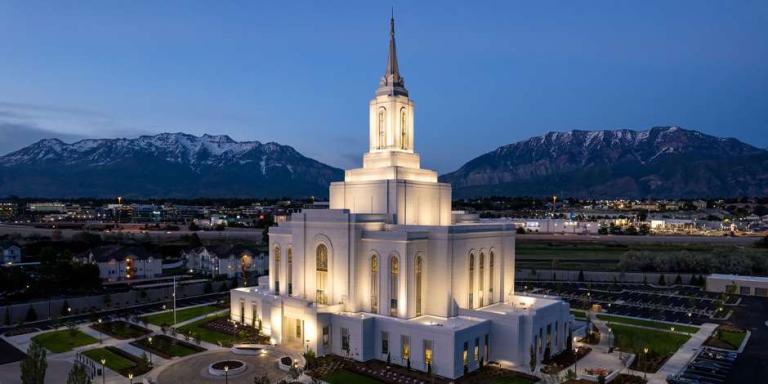

We participated in the first dedicatory service for the new Orem Utah Temple this morning. Elder Hugo E. Martinez, whom we came to know just a bit during a tour of Israel many years ago (prior to his call as a General Authority), conducted the meeting, which featured a pre-recorded video message from President Russell M. Nelson. Elder Kevin R. Duncan led those assembled in the “Hosanna Shout.” Elder Patrick Kearon, who was ordained an apostle just last month, offered some quietly touching remarks. Last of all, Elder D. Todd Christofferson of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles — who dedicated the Lima Peru Los Olivos Temple only last Sunday — spoke and offered the prayer of dedication.

It’s a great thing to now have a temple so close to us — indeed, to have so many temples so close to us. (The Orem Utah Temple is probably about a mile from our house as the crow flies, and a four- or five-minute drive on surface streets. Two and a tenth miles.) I was surprised to become quite emotional at one specific and entirely unexpected point during the dedicatory service. I’m Scandinavian; I don’t do emotions.

While in St. Paul’s Cathedral in London the other day, I picked up a copy of Paula Gooder, Heaven (London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge [SPCK], 2011). Paula Gooder (D. Phil, Oxford) is a British theologian, Anglican lay reader, and freelance writer who currently serves as Canon Chancellor of St. Paul’s Cathedral and specializes in the New Testament. With the temple very much on my mind today, I think it appropriate to share a passage from the book:

The Holy of Holies was considered so holy that it was only visited once a year, by the high priest on the Day of Atonement, and only then in a cloud of incense, that he might not see God on the mercy seat. (18)

I’m not sure that I’ve ever previously seen the claim that the purpose of the incense in the Holy of Holies was to hinder the possible seeing of a visible God. (Note, too, that God was presumed to have location [“on the mercy seat”].). But that purpose for the incense does indeed seem to be implicit in her quotation from Leviticus 16:11-13:

Aaron shall present the bull as a sin offering for himself, and shall make atonement for himself and for his house; he shall slaughter the bull as a sin-offering for himself. He shall take a censer full of coals of fire from the altar before the Lord, and two handfuls of crushed sweet incense, and he shall bring it inside the curtain [i.e., inside the veil — dcp] and put the incense on the fire before the Lord, so that the cloud of the incense may cover the mercy seat that is upon the covenant, or he will die.

She continues:

One of the confusing elements of this tradition is the question of whether human beings could or could not see God and live. The problem is that there are various strands of tradition about this throughout the Bible. The Moses tradition itself has at least two elements. One states that you cannot see God and live: ‘”But”, he said, “you cannot see my face; for no one shall see me and live.”‘ (Exod. 33.20); the other records Moses’ frequent visits to the presence of God where he stands unveiled (Exod. 34.29-35). There are others like Elijah, who wrapped his face in his cloak before standing in God’s presence (1 Kings 19.13), and others still, like the above reference in Leviticus 16.11-13 which assumes that those who see God face to face will die. It would be easy — and wrong! — to assume that in the earliest period people believed they could see God face to face and that the idea grew up over time that they could not. This clearly does not fit the evidence.

The Moses stories contain elements of both traditions. Elijah stands in God’s presence but covers his face. Isaiah sees the skirts of God’s robe (6.1) but is nevertheless terrified in the presence of God because he is a person ‘of unclean lips’ (6.5). Ezekiel expresses no apparent terror but does fall on his face before God’s throne (1.28). What this points to is that we cannot say, as some do, that you cannot see God — or the face of God — and live. Nor can we build a simple trajectory from early to late, from seeing God to not seeing God. There is a mixture of tradition in the Hebrew Bible. Nevertheless, the tradition of danger associated with seeing God certainly grows over time, so that those who see God seated on his throne do so — to borrow a modern phrase — at their own risk. In some of the later material extreme danger was associated with the situation of those who sought to stand in the presence of God but were unworthy to do so.

Despite the variety of strands in the Bible about the seeing of God’s face, there is no doubt that the Holy of Holies remained a place of great mystery associated particularly with the presence of God. (18-19)

And, once again, the very fact that there existed a notion of the “presence of God,” coupled with the association of that notion with a particular place, strongly suggests that, in the Israelite conception, God occupied a particular location.

For fairly perfunctory news coverage of today’s temple dedication — which was, of course, open only to holders of current temple recommends — see this, in the Deseret News: “Orem Utah Temple dedication a ‘milestone in the progress’ of God’s kingdom, Elder Christofferson says: The new temple, located just off Interstate 15 and near Utah Valley University, was dedicated in two sessions Sunday, Jan. 21”

A more complete account, with photographs, appears on the official Newsroom website of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints: “Elder Christofferson Dedicates Orem Utah Temple: Dedication of Utah’s 19th temple ‘marks a milestone in the progress of the kingdom of God on the Earth,’ he says”