Perhaps the first thing to understand is that members of the Eastern Orthodox tradition would find offensive any suggestion that they are not part of "mainstream Christianity." Indeed, for the Orthodox, they actually are "mainstream" Christianity, meaning, it is the Orthodox Church's position that they are the "true" Church of the New Testament. They are the only Christian denomination that fully and accurately represents what Jesus, the New Testament apostles, and the first-century followers of Christ believed and practiced. While most other Christian denominations are "good," they are not—in Orthodox thinking—an accurate or full representation of the Christian faith and message, as delivered (in the first century) by Jesus and His apostles. I suppose that's the first difference we should point out between the Eastern Orthodox tradition and the other denominations of Christianity.

Preservation of the Ancient Church

Related to this last point, one of the other things that set the Orthodox Church apart from other Christian denominations is its efforts to remain as close to the New Testament Church—its doctrines, structure, and feel—as possible. In that regard, some outside of the Orthodox tradition has seen it as "anti-progressive." The Orthodox do not use such terminology in explaining their stance. However, as suggested above, it is true that Orthodoxy generally sees the evolution of the look, feel doctrines, and practices of many of the other Christian Churches as evidence that they have strayed from New Testament Christianity. The Orthodox, on the other hand, have sought to avoid as much of that theological "drift" as possible and, thus, when one steps into an Orthodox Church, sometimes it feels a bit as though one has stepped back in time. For practitioners of Orthodoxy, this is not only part of the beauty of their tradition but also part of what evidences that it is the "true" or most "accurate" of Christian denominations.

Denominations

Another significant difference between the Orthodox Church and other Christian denominations is its structure. Unlike pretty much any other Christian Church, the Orthodox Church is made up of a bunch of smaller denominations—all united and in communion with each other but distinguished by their ethnic origins. So, you have the Greek Orthodox, the Russian Orthodox, the Albanian Orthodox, etc. However, they aren't different Churches. They are all part of the Eastern Orthodox tradition, with an Ecumenical Patriarch at its head, symbolic of the unity of all fourteen autocephalous (or "self-governing") branches of the Church. (In addition to those fourteen universally acknowledged autocephalous sub-denominations of Eastern Orthodoxy, there are also numerous autonomous branches, which are "self-legislated," but which are still under the governance of one of the autocephalous denominations.

The Trinity

While Orthodoxy believes firmly in the doctrine of the Holy Trinity, it does take a position on this doctrine that stands somewhat in juxtaposition to most protestant denominations and even in contrast to the official Roman Catholic take. Whereas modalism—the idea that the Father, Son and Holy Spirit are one God/one Person/one Being, manifesting Himself in different "modes" or "forms" at different times in history—is a fairly common belief among many low-church protestants, and even among many lay Catholics, the Eastern Orthodox disagree with this view of the Holy Trinity. Though the Orthodox emphasize the "oneness" of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, they emphatically believe that those Three divine Persons are utterly distinct—with unique roles in the Godhead. For the Orthodox, though the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit constitute the Holy Trinity and "one God" (united in divine "essence"), the Son and Holy Spirit are traditionally seen as subordinate to the Father. Thus, while the "oneness" of the Three is definitely not denied, the uniqueness of the Three is emphasized more in Orthodoxy than in most other Christian denominations.

The Filioque

Related to this last point, Orthodoxy rejects the filioque or the belief that the Holy Spirit precedes forth from both the Father and the Son. The filioque, meaning "and from the Son," was added to the Nicene Creed (by the Catholic Church) in the late 6th century, and Eastern Orthodoxy rejects that addition—not only because it changes the original text of the creed but also because it rejects the doctrine of the subordination of the Son to the Father—a doctrinal belief which distinguishes the Orthodox from the Catholics and from most protestants in their understandings of the Holy Trinity.

Christology

There have been many Christological schools throughout the history of Christianity that have attempted to clarify the nature of Jesus—beyond what the Bible explains. In the years following the death of Jesus and the apostles, you had "schools" which have been referred to as the "Heretical Left"—those who exaggerated the humanity of Jesus (e.g., Arianism, the Ebionites, the Logos-Anthropos school or Word-Man school, and the Nestorians), and the "Heretical Right"—those who exaggerated the divinity of Christ (e.g. the Gnostics, the Docetists, the Apollinarians, the Monophysitism, and the Monothelitists). What exactly the nature of Jesus the Christ was (when He walked the earth) is not universally agreed upon in Christianity. It wasn't clear in the first centuries of the common era, and Christians simply aren't in complete agreement today. From a Christological perspective, the Orthodox speak of Jesus as fully human and fully divine—one Person with two natures. He was perfectly human and perfectly divine. Jesus was begotten in pre-eternity as God's Son, having no heavenly mother, and begotten in mortality, as a man without an earthly father. This view is unique when compared to a number of other Christian denominations.

Soteriology

One major way in which the Orthodox are theologically distinctive is in how they describe salvation. In Orthodoxy, salvation is often defined in terms of "theosis" or "deification"—meaning, the ultimate goal of the Christian life is for God (through Christ) to cleanse each Christian of "hamartia" (i.e., ways in which we have "missed the mark" or the purpose of the Christian life)—thereby allowing the saved Person to share eternally in the "nature" of the Holy Trinity (though not in God's "essence"—which would be an impossibility, since we are not Gods). Thus, for the Orthodox, heaven is not simply a place that awaits the faithful. It is also the abode of those who have been deified, who have been "saved from unholiness," and who will enjoy and participate in the everlasting "life" of the Holy Trinity. While there is some discussion of theosis (or deification) in Catholic and protestant theological circles, in no tradition other than Eastern Orthodoxy is this doctrine as pronounced or emphasized (other than perhaps The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints—through their understanding of theosis is somewhat different from the Orthodox construct).

Ecclesiology

The Orthodox are somewhat unique in their ecclesiastical structure as well. The Roman Catholics have the Pope, the Anglicans have the Queen and the Archbishop of Canterbury, low-church protestants often have no worldwide ecclesiastical head, and the Eastern Orthodox have their Ecumenical Patriarch. At the risk of making this overly simplistic (principally for the sake of space), what sets the Ecumenical Patriarch apart from other worldwide leaders of Christianity is the fact that he is the acknowledged "head" of Orthodoxy—by the Orthodox and non-Orthodox alike. Yet, while he is the "head" of the communion (or conglomerate) of Orthodox denominations, he doesn't exercise the same kind of universal authority over the worldwide Orthodox Church that you would expect if you compare his office to that of the Pope or the Archbishop of Canterbury. In other words, he functions more as a symbol of the fact that all of the various sub-denominations of Orthodoxy are united, in communion, and essentially "one Church," but each of the fourteen autocephalous denominations of Orthodoxy have their own Patriarch who holds authority over that denomination and leads that denomination. The Ecumenical Patriarch, on the other hand, doesn't "run" any of the branches or denominations of Eastern Orthodoxy. Rather, he presides and represents. The Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America has offered this explanation of his role:

"As 'primus' (first) bishop of the Orthodox Church, the Ecumenical Patriarch undertakes various initiatives of Pan-Orthodox character, while coordinating relations between the other Churches of the Orthodox Communion, as well as relations between Orthodoxy as a whole and other Christian Churches or World Religions. Thus, he convokes and presides over councils and Pan-Orthodox meetings; … [and] grants autocephalous status to local churches which have become mature enough to be elevated to that ecclesiastical rank."

Additionally, whereas the Roman Catholic Church holds that the Pope has the ability to speak infallibly on matters of dogma and morality when speaking ex-cathedra, the Eastern Orthodox tradition has consistently maintained that no man—Pope, patriarch or Person—is anything more than human and, thus, none can claim infallibility—ecclesiastically, theologically, or otherwise. In this regard, the Orthodox are much like the various protestant denominations and very different from the Catholic Church. When the office of Ecumenical Patriarch is taken in totality, it is best not to see the Patriarch as the equivalent of that tradition's "pope." He does not wield equivalent authority, does not really hold a similar position, and he has roles and responsibilities which are quite different from many of those of the Catholic Pope (or even the Anglican Archbishop of Canterbury). This, too, sets Orthodoxy apart from other High-Church Christian denominations.

Clerical Celibacy

One thing that makes Orthodoxy, unlike Catholicism, but also unlike most protestant denominations, is its position on celibacy. Protestantism generally rejects clerical celibacy. In Roman Catholicism, on the other hand, those who have taken holy orders (nuns, priests, bishops, popes, etc.) are required to take a vow of celibacy. However, the Eastern Orthodox tradition falls somewhere between these two extremes. In Orthodoxy, while "higher clergy" (e.g., Bishops, Archbishops, Metropolitans, Patriarchs) are expected to be celibates, "lower clergy" (specifically parish priests) are required to be married. Among other things, the Orthodox have argued that a priest over a parish will need to counsel his parishioners on issues of marriage and family life. How can he adequately do so if he has no experience in this arena himself? Thus, celibacy—while the norm among the monks and leadership of the Orthodox Church—is largely non-existent among local parish priests (with the exception of widowers). So, the Orthodox do not fully embrace the Catholic position on this matter, but nor are they 100% in alignment with the protestant approach to clerical celibacy.

The 'Fallen' Nature of Humans

Like the issue of sexual abstention among the clergy, the Orthodox may fall halfway between Catholics and low-church protestants on the issue of the fallen nature of humankind. Yes, the Orthodox Church acknowledges the Fall—as do most Christian denominations. However, for the Eastern Orthodox, since humans are created "in the image of God," they do not say that "human nature" is "evil." Rather, their focus instead is on the reality that humans are "attracted" to sin or are "inclined" to sin. Thus, whereas Augustine focused on the guilt humans possess because of the Fall—and in the form of "original sin" or "inherited guilt"—the Orthodox largely reject this, saying instead that our humanity makes us more susceptible to sin, but we are no less endowed with "divine nature" and the potential to experience divinization through the God who has created us "in His image." Thus, the Orthodox are not really fully aligned with the Catholic or typical protestant views on this matter.

Scripture

The Orthodox are definitely different from most low-Church protestant denominations when it comes to scripture. The Orthodox accept the Old and New Testaments, but they also accept the deuterocanonical books (or books of the Apocrypha), whereas most low-church protestants don't. Also, the Orthodox tend to see the "tradition of the Church"—meaning councils, patristic sources, and longstanding teachings or practices—as equally binding. Thus, the common protestant doctrine of sola scriptura (or "scripture alone") is foreign to Orthodox thinking.

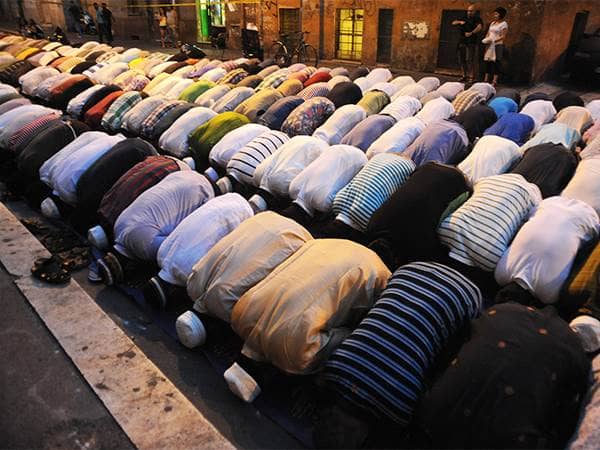

Iconography

Perhaps one of the biggest differences between the Eastern Orthodox tradition and other Christian faiths—including the Roman Catholic tradition—is the Orthodox use religious icons. These are employed quite heavily in Orthodox worship, both at Church but also at home. While the Orthodox do not perceive using 2-dimensional religious art as idolatrous, they traditionally venerate (or kiss) icons, burn incense to them, and use them in most acts of worship. For the Orthodox, icons help the worshiper to draw closer to God. They are a door to spiritual communion with the divine. Because of what they represent, they are treated with great respect and even awe—though the Orthodox are emphatic that the icons are not perceived as God, only as a representation of the divine. In Orthodox tradition, icons are not simply "nice" depictions of divine beings or holy events. Rather, they are "necessary" or "essential" in Orthodox worship, as they "safeguard a full and proper doctrine of the incarnation." They help us to understand what Jesus was. Just as an icon is an earthly matter with a divine image, pointing our minds and hearts to God, Jesus came to earth, took upon Himself a body made of "earthly matter" (but with a "divine image" or the "express image of God"—Hebrews 1:3), thereby pointing our hearts and minds to His Father, God. Thus, icons not only open the door to heaven, but they also teach us about a crucial Orthodox doctrine—the incarnation of God's Son. It is worth pointing out that, while the Orthodox will use 2-dimensional images, they traditionally avoid statuary as a part of their formal worship (in an effort to avoid breaking the commandment given in Exodus 20:4-5 about "graven images"). Thus, Catholics heavily use 3-dimensional art, and the Orthodox only use 2-dimensional icons—but both use them in very different ways. Of course, low-Church protestants typically don't use either—at least not how the Orthodox would. So, again, in this sense, the Orthodox are quite different from Catholic and protestant worshipers.

Expectations

The Orthodox are similar to other Christians in many ways, and they are different in some significant ways. One would expect some of these differences if, for no other reason than the Orthodox view that their brand of Christianity is the "true" brand—and to be the only one that's fully right, you certainly must be at least partially different.

3/7/2023 2:51:29 AM