The concept of religious pilgrimage is common in many faith traditions. Catholics famously make their way to Rome, Lourdes, or Fatima. Jews often speak of celebrating their annual Passover in Jerusalem, or making a visit to the Western Wall (at the base of the Temple Mount). Members of the Sikh Khalsa will almost certainly make to visit the Golden Temple in Amritsar, India, it being their most sacred and revered gurdwara. For Buddhists, the location of Sidhartha’s birth (in Nepal) is their most important pilgrimage destination; but a visit to Bodh Gaya (where the Buddha gained enlightenment) is also a moving and sacred experience. For Latter-day Saint Christians, visiting one of their 350 temples scattered throughout the world is believed to be a religious duty. And, for practitioners of Islam, visiting Mecca at least once in their lifetime (during the prescribed month) is considered obligatory for all who are able.

The word ḥajj is Arabic and means “pilgrimage.” The month in which the ḥajj takes place is Dhul Hijja, which (literally translated) means “pilgrimage month” or “month of the pilgrimage.” The Islamic ḥajj is one of the “Five Pillars” of Islam—meaning it is one of the five fundamental tenets or obligatory practices of every observant Muslim (in the various branches of Islam). Thus, Muslims believe that (if their health and finances allow, and their family would not be adversely affected by their participation) they are obligated to make a pilgrimage to Mecca, thereby showing their complete and utter submission to Allah. Though the annual pilgrimage is central to Islam, Muslims hold that the Prophet Muhammad (circa 570-632 CE) [PBUH] did not begin the ḥajj, though he participated in it. Rather, it is claimed the biblical patriarch Abraham was the first to begin the ḥajj. (Qur’an 22:26-30) However, by the time of Muhammad, Mecca had become a place filled with idols and false gods, and pilgrimage to that sacred site had largely become corrupted. Indeed, the Qur’an states that so corrupt were things at the Ka‘bah (in Mecca) leading up to the restoration of Islam, that “Their prayer at the Sacred House was nothing but whistling and clapping.” (8:35) Thus, the Prophet [PBUH] cleansed the Ka‘bah of its various idols, ended the numerous vain and pointless practices, and established a pure form of the ḥajj.

There is actually more than one kind of ḥajj. Indeed, some Muslims acknowledge three different pilgrimages. The first and most important is al-Ḥajj (or “the greater pilgrimage”). This is the only of the three which is considered “canonical” or commanded; and is the only one that fulfills the requirement of the “fifth pillar” of Islam. This is the ḥajj we’ll focus on in this article. However, there is also al-’Umrah (“the lesser pilgrimage”). This ḥajj to Mecca can be performed any time of the year (except during al-Ḥajj), and only incorporates certain components of the “greater ḥajj.” Thus, it is essentially an abbreviated version of the full ḥajj, but carries less significance. The third pilgrimage acknowledged by some Muslims is az-Ziyārah (or the “visit”). This is a pilgrimage to the grave of the Prophet [PBUH], which is located in Medina—just north of Mecca. This third ḥajj is not only non-canonical, but it is also not considered a “rite” (whereas the other two qualify as an actual “rite” of Islam). Importantly, there is a Hadīth that actually forbids making a pilgrimage to Muhammad’s [PBUH] grave. Thus, many Muslims see this third ḥajj as inappropriate.

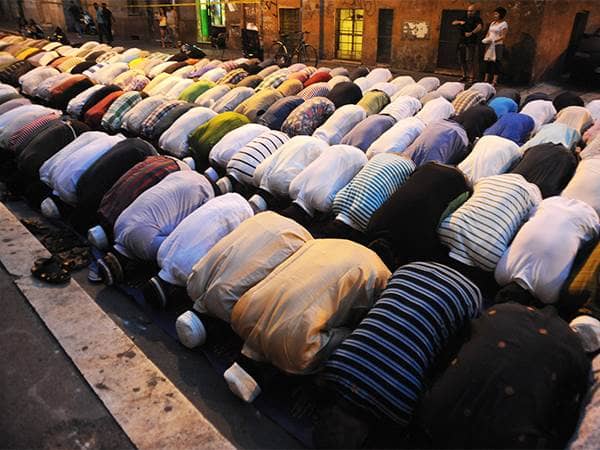

During al-Ḥajj, there are a number of important activities and elaborate rites which are engaged in as part of this multi-day pilgrimage. Each of these take place in the Grand Mosque of Mecca and in the immediate surrounding area.

Day One (8th of Dhul Hijja)

This first day of the ḥajj is often called the “day of reflection” or the “day of deliberation.” Prior to entering the city of Mecca, one must enter into a state of iḥrām (or “consecration”). This requires ritual washing (i.e., ghusl or wuḍū) and, for men, the donning of two large pieces of white cloth that are seamless and unstitched. This is sometimes called the “costume” of the “pilgrim.” (Women wash as well but are not required to don special clothing—other than their traditional modest dress.) The pilgrim then engages in the “circumambulation of arrival” wherein he or she walks around the Ka‘bah seven times. In an ideal situation, one is close enough to the actual Ka‘bah to touch and kiss the “Black Stone” on the eastern corner of the sacred shrine. However, owing to the presence of millions of worshipers engaging in this same circumambulation (all at the same time), few are fortunate enough to actually do this. Thus, one may simply gesture toward the stone (if not able to actually touch it). Once the seven circumambulations are completed, the pilgrim offers a prayer facing the Ka‘bah and its stone. Next, the participant moves to or near the Maqām Ibrāhīm (also known as the “Station of Abraham”) where he or she offers a prayer at or near a foot imprint said to belong to the ancient Patriarch. The pilgrim then takes a drink of the water of Zamzam. (This is water from the well that the Bible says miraculously appeared, saving the life of Abraham’s son, Ishmael, and the boy’s mother, Hagar/Hajar. See Genesis 21:19.) Finally, at the conclusion of this day’s ritual activities, most pilgrims head to Minā, where they spend the night; though some head directly from Mecca to ‘Arafāt.

Day Two (9th of Dhul Hijja)

The second day of the ḥajj is called the “day of standing” or, less commonly, the “day of ‘Arafāt.” If not already in ‘Arafāt, the pilgrim heads there (from Minā). Under the direction of an Imām, the afternoon and late afternoon prayers (combined together and shortened) are said. This represents “standing” before Allah—hence the name of this second day of the ḥajj. Indeed, most see this day’s rites as a foreshadowing of the Day of Judgement when all will stand before God to be judged according to his/her deeds performed in this life. On this second day, participants repeatedly recite the talbiyah, which (according to the Qur’an) consists of Abraham’s call to humans to participate in a pilgrimage to Mecca: “Here I am [at your service] O God, here I am. Here I am [at your service]. You have no partners (other gods). To You alone is all praise and all excellence, and to You is all sovereignty. There is no partner to You.” This prayer is seen as the central invocation of the ḥajj; and the events of day two are focused on examination of one’s conscience, anticipation of judgement, and prayer to Allah. (Some pilgrims will climb to the top of the “Mount of Mercy” to offer this invocative prayer, though it is permissible to offer it anywhere in ‘Arafāt.) After sundown, on day two, pilgrims usually head to Muzdalifah, where they engage in the sunset and nighttime prayers for the day; again, with the two being combined into one prayer.

Day Three (10th of Dhul Hijja)

For those participating in the ḥajj, this third day is referred to as the “day of sacrifice.” Pilgrims offer prayer at the monument of al-Mash‘ar al-Harām. This monument marks the spot where the Prophet Muhammad [PBUH] prayed to God during his “Farewell Pilgrimage.” Participants then gather small pebbles which (in times past) were thrown at three stone pillars. In stoning the pillars (representing the devil and his temptation), the pilgrim is symbolically rejecting Satan and his temptations. They are, in essence, casting him out of their lives. (In 2004, Saudi authorities replaced the three pillars with a stone wall, against which the pebbles are now thrown. This change was made to prevent pilgrims from accidentally stoning other pilgrims who were standing opposite of them.) On this third day, a sacrifice is made (usually consisting of a ram or sheep, but an ox or camel may also be used.) This is most commonly done by purchasing a voucher that pays for the sacrifice and ensures its completion. If one chooses, participation in the animal sacrifice can be replaced by ten days of fasting—three during the ḥajj and seven after one returns home from their pilgrimage. As the third day nears its end, the pilgrims have their hair clipped. Women traditionally just have a small lock removed, while men may do the same, but many males will have their entire heads shaved. The final acts of this day will include the tawaf al-ifadah (or the “farewell circumambulation” of the Ka‘bah) and sa'y (or the “running”) between two hills—Safa and Marwa. (This is more of a walking back and forth seven times between the two hills, rather than an actual “running.” It symbolically suggests one’s efforts to “strive” or “pursue” Allah’s will.)

Final Days (11th—13th of Dhul Hijja)

The last three days of the ḥajj are commonly called the “days of drying the meat” (referential to the animal sacrifice made the previous day). The meat is distributed to the poor, either as jerky, fresh meat, frozen, or canned. Pilgrims who remain in the region after day three will typically stay in Minā and will throw twenty-one pebbles at the wall representing the devil and his temptations. Aside from a few non-obligatory practices, this largely concludes the ḥajj.

So sacred is this act of pilgrimage and its attendant rites, most Muslims believe that once you’ve started your ḥajj, and entered ihrām (or a state of “consecration”), you are obligated to finish each of the associated rites of the pilgrimage. The sole exception to this would be if something absolutely prevented you from completing your ḥajj (such as incapacitation or death). As another evidence of the sacredness, importance, and even reverence associated with completing the pilgrimage, those who have done so are authorized to add the prefix al-Ḥājj (or “pilgrim”) to their name. So, for example, one would go from simply being Amir to “al-Ḥājj Amir” (meaning, “Amir, the pilgrim”). Muslims greatly respect other Muslims who have made the sacrifice to properly complete a ḥajj.

Over the last 1,300 years, there have been a number of tragedies that have happened during the ḥajj, resulting in the death of many people. Most of these deaths took place because of the extremely high number of people who participate in the ḥajj annually. (In 2012, for example, more than 3.1 million pilgrims took part in the ḥajj.) As an illustration of a common catastrophic occurrence, in September of 2015, more than 2,400 pilgrims lost their lives—being crushed in a human stampede. At the June 2024 ḥajj, with temperatures in Mecca reaching 125 degrees, more than 1,300 pilgrims died of heat-related causes. Owing to the commonality of deaths that take place during the ḥajj, some have criticized the command for Muslims to engage in the pilgrimage. However, focusing on the deaths actually risks missing the point of the ḥajj, its meaning, and its spiritual significance and impact. The reality that so many converge on Mecca each year for this sacred event, and the very fact that many have quite literally given their lives to participate, is a testament to the faith and faithfulness of these people. It is a demonstration of their love for God, their devotion to Him, and their complete and utter submission to the things which they believe Allah—through His Messenger [PBUH]—has commanded them. We should no more condemn Islamic participants of the ḥajj for their devotion than we would Christian martyrs who refused to deny their faith, knowing that the Romans would put them to death if they insisted on embracing Christianity and Jesus, or if they lived an openly Christian lifestyle. Rather than seeing the risks innate in the ḥajj as unwise, observers should have a measure of “holy envy” for the faith and devotion of those who make this incredible sacrifice each year, and for their love of God and His laws.

One source noted that the “significance and message” of the ḥajj is that we must each “turn towards God, making [Him] the central focus of” our lives. In reality, there probably isn’t a religion on the face of the earth that doesn’t teach something similar about our duty to the divine. The Arabic word “Islam” literally means to “submit” or “surrender”—as in surrendering one’s will to God. One can only do that by making Him the primary focus of his or her life. The ḥajj is one of the many ways in which Muslims do this. There is a common saying that appears in various religions; namely that “pilgrimage is a journey to the center of the heart.” That’s true in Islam as much as it is in any of the religions who have pilgrimage as part of their devotional practice. Muslims who engage in the ḥajj—whether once or repeatedly throughout their lives—are showing what’s in their hearts; namely, a love for God, a willingness to sacrifice, and an attitude of complete submission or surrender to the divine. Regardless of your personal religious beliefs, if properly understood, each can see both the requisite sacrifice and the commendable nature of pilgrimage, for such journeys really mirror the mortal experience. Just as the pilgrim, through great sacrifice and concerted effort, makes his or her way to the sacred site, you and I spend our own lives (as devotees) slowly, concertedly, and with great sacrifice, seeking to make our way to the “sacred site” which is God’s heavenly abode. Thus, we might say, pilgrimage is simply a “dress rehearsal” for the ultimate goal of all religions—making their way into the presence of God.

6/26/2024 4:46:32 PM