What should we teach about Islam?

What should we teach about Islam?

by Waqar Ahmedi

Waqar Ahmedi is head of Religious Education at one of the leading comprehensive schools in Birmingham, UK.

He is a member of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community, and has served his community in a number of capacities including regional youth leader and chair of education in the Midlands.

In the essay below, Ahmedi explains what we should teach about Islam in the politically charged climate today.

What a roller coaster of a year 2015 was – especially if you teach about religion.

The frenzied debate about free speech post-Charlie Hebdo, spate of ISIS terror attacks and, yes, Donald Trump, propelled classroom practitioners like me into relentless action.

But these things and more also made us rethink how we discuss faith in the classroom.

While every RE specialist believes that there isn’t a more fascinating subject to teach, it has also become one of the most challenging. Facilitating pupils’ exploration of beliefs and truth claims comes with both pleasure and pressure. Educators are in positions of great privilege and influence; we are tasked with preparing students for a world that is ever changing, and where religion will have an impact on them as global citizens. And we need to do it right.

Events this year brought the RE community much closer, to try to come to terms with so much that has happened, and to consider the implications these developments have for our curriculum and practice.

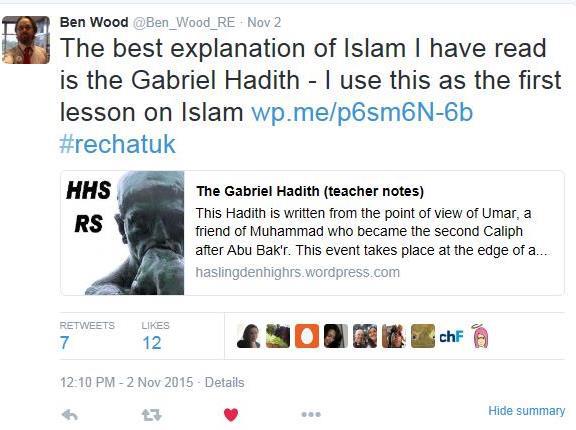

Social media was abuzz with RE teachers sharing ideas and resources of how to counter sensationalist headlines that often colour pupils’ perception of religion – and Islam in particular.

The ‘ISIS crisis’ has made many practitioners feel that they must defend the Muslim faith. From using the #NotInMyName campaign on Twitter to a beautiful verse from the Qur’an recited in Eastenders, teachers have been keen to show that Islam is a religion of peace.

However, questions have been raised about whether this is really the job of RE teachers. Are we expected to promote religions as torchbearers of tolerance and love, or do we have an obligation to show that faiths have both positive and negative facets, and allow pupils to form their own judgements?

The ‘Report of the Commission of Religion and Belief in British Public Life’ published earlier this month stated that “the content of many [RE] syllabuses is inadequate” focusing on “a rather sanitised or idealised form of religion”. Religions, it said, are portrayed “only in a good light” and schools “tend to omit the role of religions in reinforcing stereotypes and prejudice around issues such as gender, sexuality, ethnicity and race, and the attempts to use religion as a justification for terrorism.”

We know that there can be an ugly side to religious commitment. We cannot pretend that all Muslims are peaceful, any more than all Jews, Christians, Buddhists, Hindus and Sikhs are. Nor can we ignore the fact that there are passages in holy texts that are used to spread hate and promote violence.

As devoted as I am to my Muslim faith, I cannot (and do not) allow that to prejudice my delivery of the subject. As I have said before, when I’m in the classroom, I’m a teacher, not preacher.

Being both an RE teacher and Muslim requires me to encourage critical thinking – about Islam too. The Qur’an itself invites readers to find faults with, or match, the word of Allah:

“And if you are in doubt as to what We have sent down to Our servant, then produce a Chapter like it, and call upon your helpers beside Allah” (Chapter 2 Verse 24)

The Prophet Muhammad was mocked throughout his ministry, but was commanded to speak to people “with wisdom and goodly exhortation, and argue with them in a way that is best” (Chapter 16 Verse 126).

Therefore, I continue to support balanced, objective teaching that both appreciates and appraises the tenets and traditions of all religions, including my own.

One of the complexities of RE remains its status in education. Though not a national curriculum subject, schools still have a statutory requirement to teach it. Standing Advisory Councils for RE (SACREs) in each local authority devise a syllabus that is considered appropriate to their area. What this means is a lack of uniformity: syllabi in one part of the UK will not be the same as another.

There are certain benefits to this, but also means that ‘religious literacy’ would, and does, look different around the country. Many students would have learned something about Islam in primary or secondary schools, but a large number also go through these years without having studied anything at all.

In November, the National Association of Teachers of RE (NATRE) hosted an online chat on the question ‘What does it mean to be religiously literate about Islam?’ Many interesting contributions were made about current practice and how this perhaps needs to change.

Teachers felt that RE lessons were too frequently influenced by media headlines, and that we must ensure that Islam is taught as a belief system, rather than as a news item. The following were identified as some important features of learning:

- the nature, history and importance of the main sources of Islam – the Qur’an, Sunnah and Hadith

- the person and prophethood of Muhammad, key events in his life, and also that of his caliphs

- core beliefs, such as the five pillars and six articles of faith, in greater depth

- Islam’s intellectual tradition, and how Muslim contributions in science, mathematics and philosophy historically have influenced much of Christian and Western thought

Additionally, teachers agreed there was an increasing need to recognise the huge diversity in the ummah. The two main branches in Islam, Sunni and Shi’a, are well known, but there are numerous denominations both within and outside each of these groups – Sufi, Barelwi, Ahmadiyya, Ithna Ashariyya and Ismaili to name but a few – that are rarely (if ever) taught.

Whilst the Qur’an, Sunnah and Hadith have authority for all of them, the theological differences are many. These relate to beliefs about a host of things, from the theory of the abrogation of the Qur’an and prophecies about the Mahdi, to the permissibility of celebrating Muhammad’s birthday and praying to the dead.

Literacy about this diversity is particularly important to differentiate between what Islamic sources say, and what a lot of Muslims believe and do. Muslim-majority countries are usually a bad example of Islam, especially when it comes to the hot-button issues like blasphemy and apostasy. These are cited as punishable by death under ‘shari’ah’, though ‘shari’ah’ itself is a term for religious laws based upon a certain reading or interpretation of the sources that can differ from one school of thought to another.

Muslim scholars and jurists also pass different (even conflicting) judgements on such issues. These are known as ‘fatwas’, which again represent only a legal opinion, and therefore are not binding on every Muslim. It is often the case that while some sects will use the Qur’an or hadith to justify particular punishments for certain actions, others will use the same sources to make the case for permitting them. Not all Muslims believe that ridiculing or leaving Islam are capital crimes.

Therefore, while the Saudi authorities may be the custodians of the holiest sites for Muslims, they are certainly not custodians of Islam. Ironically, Islam and the West have more in common when it comes to notions of equality and freedom, than the Qur’an and some Muslim countries do. As the 19th century Islamic thinker Muhammad Abduh is attributed with saying: “I went to the West and saw Islam, but no Muslims; I got back to the East and saw Muslims, but not Islam.” Much of that still rings true today.

I agree with RE blogger Alan Brine that the claim of some Muslims to have authority for their ‘version’ of Islam should not be taken as a baseline for our teaching about the religion. However, I’m not so sure that “different Islams, some pleasing, others distasteful, are all just versions of Islam.” This suggests that both pacifist and jihadi manifestations are equally ‘Islamic’, akin to saying that the Quakers and Ku Klux Klan are equally ‘Christian’.

There is, then, a need for greater rigour when it comes to the study of religions like Islam. The Department of Education’s guidance on the new GCSE Religious Studies courses appears to promote just that, including a focus on ‘origins of differences and implications for questions of authority’. This should allow scope for the examination of not just multiple approaches to understanding Muslim sources, but the authenticity of the Qur’an too.

It is important that students engage with scholarship and current debates about this. There has been some disagreement within the RE community about how this should happen, and which voices to pay attention to – and the ones that shout the loudest (or rather, given more airtime) are not necessarily the most helpful.

One is Tom Holland, a historian who has been appearing regularly on mainstream TV and radio as an expert on Islam, and recently claimed that the ancient Qur’an fragments discovered at the University of Birmingham may have even pre-dated Muhammad. He appears actually to have little credibility for his work, being widely criticised for commentating on Islam without any specialist knowledge of its texts or Arabic, and lacking historical acumen. Holland’s scholarship, if it can even be called that, has yet to be treated seriously by any reputable academic in the field of Islamic research.

Another is Ayan Hirsi Ali, author of Heretic who has frequently spoken out against Islam (she left the faith to become an atheist), and called for its reformation. Similarly, her poor understanding of the sources, not to mention her bigotry, have been frequently exposed. In any case, Holland and Ali’s call for a reinterpretation and revisionism of Islamic tradition offers nothing different to the continuous process of Qur’anic exegesis and ijtihad that mufassireen and every generation of Muslims have undertaken since the 7th century.

If anyone wants to study respected modern scholars, ranging from the popular to the sceptical, the likes of Karen Armstrong, Jonathan Brown, Hugh Kennedy and Chase Robinson are a good start. Another highly recommended read is the award winning Muhammad in History, Thought and Culture: An Encyclopaedia of the Prophet of God, edited by Coeli Fitzpatrick and Adam Hani Walker, featuring articles about Islamic history from specialist contributors across the world.

This sort of reading has become particularly important at a time when there is huge demand for more CPD on Islam in preparation for the teaching of the new GCSE and A level specifications in 2016.

Some online courses, such as The Introduction to the Qur’an: The Scripture of Islam and Dr Chris Hewer’s Understanding Islam course (both are free), have been found to be extremely useful.

There is also wealth of expertise in the RE community; NATRE has run some excellent sessions on Islam, and it is great to see local RE groups offer specialist training to help equip teachers with the knowledge, insight and confidence they need to deliver the new courses effectively.

I also hope that the new series of GCSE textbooks and resources on Islam that I am writing for Oxford University Press reflect quality content that helps facilitate the support and challenge needed to bring out the very best in our students.

As we enter the New Year, let the RE community continue to share practice and keep working together to achieve that.