The Church of Scientology was founded in the 1950s by L. Ron Hubbard (1911-1986), a graduate of George Washington University and author of sci-fi and fantasy literature. Between 1934 and 1940, Hubbard published hundreds of short stories and novels. In addition to his various works of fiction, Hubbard also authored a semi-philosophical text known as Dianetics—the content of which he indicated he had drawn not only from his personal life experience, but also from the teachings of Sigmund Freud combined with aspects of Eastern religion/philosophy. First published in 1950, Dianetics was written prior to Hubbard’s founding of the Church of Scientology. Nevertheless, the text became influential in the Church once organized.

The date of the founding of Scientology has been variously reported as 1952, 1954, or 1956. In actuality, it was officially incorporated in December of 1953 (in Camden, New Jersey), but the Church’s first branch (which was in Los Angeles) wasn’t opened until 1954. However, because Hubbard had organized what he called the “Association of Scientologists International” (or “HASI”) in 1952, some have erroneously assumed that the Church of Scientology had been founded earlier than it actually was.

At the time Hubbard wrote and published Dianetics, it doesn’t appear that he was interested in Scientology as a religion or a religious organization. Rather, Hubbard seems to have initially envisioned the movement as a detailed theory about how the human mind functions, and how one could be equipped to prevent the “clouding” of one’s “analytic mind”—a clouding which Hubbard believed was caused by “traumas” (in this life or in previous existences). The “clouding” of the mind prevents one from experiencing or seeking “reality,” according to Hubbard. This teaching strongly mirrors “maya” (or “illusion”) in many of the East Asian traditions—and Hubbard, by his own admission, may have drawn the teaching from his study of the dharmic traditions.

It wasn’t until 1953 that Hubbard first openly contemplated Scientology as a religion, though he may have toyed with the idea prior to expressing his interest (in April of 1953) in a letter to the manager of HASI (Helen O’Brien). In his letter, Hubbard requested that O’Brien look into the religious “angle” of Scientology. Though she is said to have been skeptical, Hubbard was convinced of its viability as a religion and, as a result, later that same year he incorporated the Church of Scientology, and officially began the transition from a philosophical-psychological movement to what some describe as a “New-Age Religion.”

The religious side of Dianetics may have been latent in the original text, even before Hubbard founded the “faith.” According to Hubbard, on January 1, 1938, during an oral surgery, he had a “near-death experience” (while under anesthesia). During this experience, he received the “inspiration” to write a book which he called “Excalibur.” Though he tried to get the manuscript published, but to no avail, “Excalibur” essentially became the basis for Dianetics. Thus, a pseudo-religious experience was Hubbard’s stimulus for writing his non-religious Dianetics text, which would eventually find its way into the “canon” of the Church of Scientology. In time, Hubbard himself would read the text less through a purely psychological perspective, and more through a spiritual-religious set of lenses.

Hubbard eventually lost the rights to Dianetics (supposedly because of bankruptcy). Not long after that, he stated that he had “discovered” a “science beyond Dianetics,” which (for obvious reasons) he named “Scientology.” The purpose of Dianetics was to facilitate the practitioner’s move beyond the “clouded” mind to a state of “clear” (allowing the practitioner to become “refamiliarized with his capabilities” or potential). However, Scientology would take the “believer” beyond what Dianetics could offer—providing practitioners with the potential to achieve an “operating thetan,” a condition of comprehensive “spiritual freedom” in which the practitioner is a “willing and knowing cause over life, thought, matter, energy, space and time.” This latter state has been described as a “state of godliness,” because the Scientologist is now in control of all things… omnipotent, in some sense of the word.

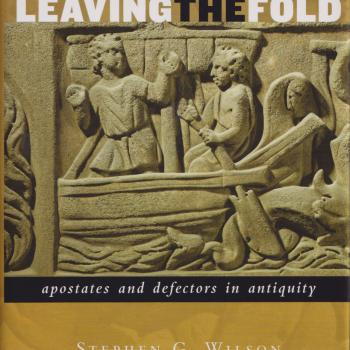

Hubbard turned out to be a somewhat controversial figure, not only because some questioned the religious nature of Scientology, but also because of several criminal charges brought against him, and because of his engagement in bigamy. Detractors of Hubbard and Scientology often raise these issues to discount the validity of the Church, though many Scientologists argue that the validity of Hubbard’s theology cannot be dismissed simply because of his human failings; something all of us exhibit.

Because of the various controversies which swirled around Hubbard and his Church, he left the United States, living for a time in Rhodesia, Greece, Morocco, the Canary Islands, and on a yacht which traveled from place to place looking for refuge from those who sought his arrest. Having returned to the United States (in 1975), Hubbard was forced into hiding (in February of 1980) in an effort to evade authorities who were pursuing him. Though, in 1967, he claimed he had relinquished his control over the Church of Scientology, it is believed that he was secretly running the organization until his death (in 1986).

Whether rightfully or not, nearly forty years after his death, L. Ron Hubbard remains a controversial figure. The Church of Scientology has certainly suffered because of Hubbard’s various controversial acts, through a sort of “guilt by association.” However, in addition to Hubbard’s persona, which has brought challenges to his movement, his unique doctrines—which lay at the core of Scientology—have also caused many to question the validity of the movement he started nearly 75 years ago.

6/3/2024 3:26:23 AM