Progress is empty, but that doesn’t mean that progress in Zen practice is unimportant. Just like there are no ears (as the “Heart Sutra” proclaims), but still many people have awakened through hearing.

And the Buddha of the Pali Canon often says that if practice isn’t efficacious, it isn’t Buddha’s practice. Indeed, many Zen students lament, most often in self-talk, “Why, oh why, is my practice not progressing?”

There are at least three diagnostic considerations – best taken up with one’s teacher, of course – intention, method, and application.

Click here to read an ad-free version of this post and to support my Zen teaching practice, including translations and writings like this.

First, is your intention to fully awaken strong and clear? If your intention is strong and clear, is the awakening you aspire for mostly about saving your own ass or freeing all beings? If your intention is not strong and clear or if it is self-focussed it simply lacks the power of the bodhisattva’s great compassion and awakening will take a kalpa or two.

To cultivate intention, mindfully reflecting on the completely fleeting nature of this life AND how we’re all in this suffering world together. Study can be of considerable help. For example, texts like Dogen’s “Arousing the Bodhi Mind” and Shantideva’s Guide to a Bodhisattva’s Way of Life are highly recommended. For a biographical approach, nothing beats Hakuin’s Wild Ivy.

Liturgy practice is also important. Frequently (not just in formal practice sessions) entoning “The Great Vows” and “The Ten Line Kannon Sutra” are particularly powerful practices.

Second, have you received appropriate instructions from your teacher on the lineage methods for initial awakening and post-awakening training? The primary method, of course, is the relationship with a Zen teacher who has walked this path and been authorized by someone who has walked this path.

Within the context of the teacher-student relationship, methods for zazen (including posture and breath), koan, study, and engaging the world are offered to the student. If your intention is strong, clear, and altruistic, but you haven’t received such personalized instruction, that’s the place to begin. Further, if you have received such instruction, have you probed the meaning of the instructions with your teacher, so that you have a deep understanding of them? Exposing and releasing faulty assumptions about method is a vital part of the process.

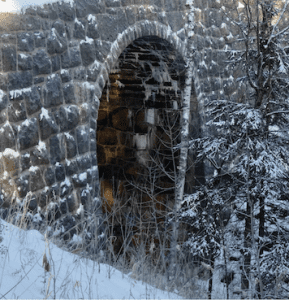

“Progress is not a matter of far or near, but if you are confused, mountains and rivers block your way.” – Shitou

Third, are you applying the instructions with fidelity and vigor? Or are you continuing to practice self-styled work arounds? If you have a strong, clear, and altruistic intention, if you have received the “inside the room” methods from your teacher’s lineage, and you are stuck, this is the place to look. In our Vine of Obstacles work, in practice meetings with students, we often address process/method issues rather than assume that the student understands. Even if we think that the student has received the instructions many times, we know that it is one thing to hear the instructions and another to apply them in actual practice.

In addition, are you applying the methods half-heartedly or wholeheartedly? Do you really show up when you meet your teacher or do you hold back, rehearsing the same safe formula again and again? Do you apply the methods for zazen, for example, diligently throughout a session and as often as possible (at least an hour a day, but two hours is much better) or do find excuses not to sit and when you do get your butt on the cushion, do you space out most of the time or allow yourself to race down mind roads?

If your answer to these questions is (a sheepish), “Yes,” then begin again by clarifying your intention.

My old friend and mentor Yvonne Rand used to have a card on her altar that said, “It takes as long as it takes.” Even if your intention, methods, and application are all in fine shape, it still takes as long as it takes. So enjoy the process.

If you want to study the Buddha Way, love the way of Buddha.

Dōshō Port began practicing Zen in 1977 and now co-teaches with his wife, Tetsugan Zummach Sensei, with Vine of Obstacles Zen, an online training group. Dōshō received dharma transmission from Dainin Katagiri Rōshi and inka shōmei from James Myōun Ford Rōshi in the Harada-Yasutani lineage. He is also the author of Keep Me In Your Heart a While: The Haunting Zen of Dainin Katagiri. Dōshō’s translation and commentary on The Record of Empty Hall: One Hundred Classic Koans, was published in 2021 (Shambhala). His third book, Going Through the Mystery’s One Hundred Questions, is now available. Click here to support the teaching practice of Dōshō Rōshi.