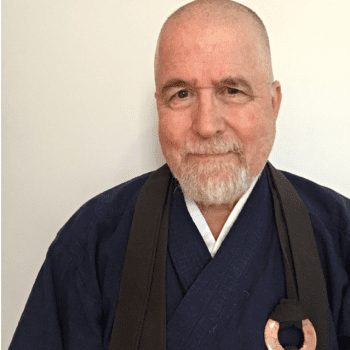

(Senior dharma teacher with Empty Moon Zen, Dr Chris Hoff offered a meditation on the fine art of boredom at our Saturday Zazenkai on the 3rd of August, 2024. I asked if I could share this at my Monkey Mind blog, and he graciously consented. A worth while read for anyone who cares in any way about the spiritual life…)

All of humanity’s problems stem from man’s inability to sit quietly in a room alone.

– Blaise Pascal

I like most people was initially drawn to Buddhism because of the counterculture literati of the 50’s and 60’s and their interest in Buddhism. Folks like Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac and of course Allan Watts. It wasn’t just the cool factor that drew me to Buddhism, although that helped. What ultimately had me diving deeper than the surface coolness associated with Buddhism in the west, was a heart that hurt. I don’t think I am alone in this entry way unto the path. You know, struggling in the world but looking for a compelling alternative to mainstream religion which I had found cold and not very useful. I think many of us were first introduced to Buddhism or Buddhist ideas via someone from the counterculture. It can be argued that what was once a minor religion in the west, a darling of the counterculture, is now becoming more mainstream. The Pew Research Center expects the Buddhist population in North America to grow to nearly 6.1 million by 2050. Sure, much of that growth will come from immigration and cultural Buddhists, but I imagine a small bit of that growth will be people like me, looking for a compelling alternative to what the dominant culture has to offer. Which raises the question. Do we still offer a compelling alternative to dominant culture?

Recently I have read a couple of books by Byung-Chul Han. For those that might not be familiar he is a South Korean-born philosopher and cultural theorist living in Germany. He was a professor at the Berlin University of the Arts and still occasionally gives courses there. I have read two books by Han, the first being The Burnout Society which I found compelling, and the second book was The Crisis of Narration which I also recommend. While not a Buddhist he is familiar with Buddhist teachings. Referencing Dogen for example.

In these two books he argues that we have some new and unique problems in our contemporary culture. These include Immediacy, acceleration, and an information deluge. He particularly points his critique at our information society brought about by tools like the smart phone. Han writes that the tsunami of information we experience now permanently stimulates our perceptual apparatus. In other words, we are never bored, and all the information fragments our attention and prevents what he calls contemplative lingering which he believes is essential to presence, and careful listening. What he calls contemplative lingering, Zen might call paying attention. So what does this all mean? What is at risk?

Han writes that what will perish is the experience of presence.

If I were honest with myself, over the last several years since the birth of the smartphone and its associated apps, I too have noticed a fragmenting of my attention. Fortunately, I do have a regular meditation practice. It’s been my saving grace.

This leads me to the point of this talk. There has been another cultural development that I have noticed and that Han points to in his writing on burnout, immediacy, and time. That is an increasing inability to tolerate boredom by many folks. I see this in my work as a therapist and just in my travels out in the world. I’ve also seen it in my work in addiction treatment, and as someone in recovery. In those contexts, I quickly learned that one of the problems that would pull people off the course of recovery was boredom. You’ll even see it in Zen. People coming and going. James shared a story with me recently when I told him I was writing a talk on Zen & Boredom about the one and only time he sat a retreat with the Korean Zen Master Seung Sahn. James shared with me that during the retreat someone asked him about watching people come to practice for a day, a week, a year, but then they eventually leave. The student asked, why does this happen? And Seung Sahn responded with well, Zen is boring!

Zen is boring. That is one of the beauties of it. And one of the reasons we can still claim to be countercultural. Nobody knows how to do boredom anymore. In Han’s book, The Burnout Society, he examines modern society’s emphasis on constant activity and productivity and offers up boredom as an antidote. I’m discovering in my own life the paradoxical nature of boredom. That on the other side of something that seems intolerable is a lot of creativity and self-reflection.

Buddhism is ripe with teachings about the suffering we invite into our lives by our constant grasping and aversion. The constant struggle for things to be different than they are. Unfortunately, there is no escape. I heard a saying somewhere that goes, the time you kill kills you in return, in the end. The avoidance of all the emotional states we find uncomfortable, are costly. It doesn’t have to be that way, especially with boredom.

This brings me to an insight shared by the poet Russian Joseph Brodsky during his 1989 commencement address at Dartmouth College. To start his talk, he shared a prediction. A prediction that stands true for any person taking up a Zen practice. He started his address to the students by saying, A substantial part of what lies ahead of you is going to be claimed by boredom. Again, a fair warning for anybody embarking on the Zen path. He went on to say

Known under several aliases – anguish, ennui, tedium, doldrums, humdrum, the blahs, apathy, listlessness, stolidity, lethargy, languor, accidie, etc – boredom is a complex phenomenon and by large a product of repetition. It would seem, then, that the best remedy against it would be constant inventiveness and originality. That is what you, young and newflanged, would hope for. Alas, life won’t supply you with that option, for life’s main medium is precisely repetition.

Brodsky’s words resonate deeply with my experience of Zen practice. When we sit in meditation, often our first encounters are with restlessness and a desperate search for distraction. But as we lean into this discomfort, something profound begins to happen. The superficial layers of our consciousness start to peel away, revealing a depth we often overlook in our busyness. All this requiring repetition.

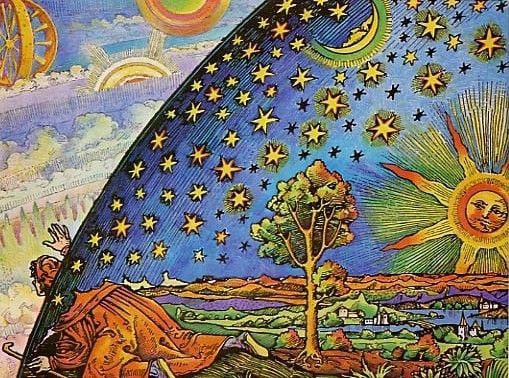

This is the paradox of boredom: what seems like an intolerable state can become a profound source of creativity and spiritual insight if we allow ourselves to sit with it. In a world obsessed with constant stimulation and productivity, learning to embrace boredom is an countercultural act of resistance —a return to our true nature.

In our practice, we are encouraged to confront our boredom head-on. This confrontation is not a passive resignation but an active engagement with the present moment, no matter how mundane it may seem. By doing so, we uncover much, including the mystery of creativity and the spiritual life that lies on the other side of boredom. We find that within the stillness and simplicity of just being, a wellspring of insight and inspiration awaits.

When boredom shows up Brodsky offers more advice,

Once this window opens, don’t try to shut it; on the contrary, throw it wide open. For boredom speaks the language of time, and it is to teach you the most valuable lesson in your life — the lesson of your utter insignificance. It is valuable to you, as well as to those you are to rub shoulders with.

Zen teaches us that awakening is found in the most ordinary moments—washing dishes, walking, breathing. When we embrace these moments without seeking to change them, we touch the intimate. This practice of presence, what Han calls contemplative lingering, is where we reclaim our sense of no-self and enter the mystery of the world around us.

So, what does this mean for us as practitioners and as a community? It means we have a responsibility to cultivate spaces where boredom is not just tolerated but embraced. Our meditation halls, our homes, our daily routines can become sanctuaries of stillness where creativity and spiritual practice flourish.

Let us remember that in a culture that demands constant engagement and distraction, choosing to sit quietly in a room alone is a radical act. It is an act of reclaiming our humanity, our creativity, and our connection to the mystery.

I encourage you going forward to reflect on these questions: How can you create more space for boredom in your life? How can you lean into the discomfort of stillness and discover the treasures that lie within? And how can our community support one another in this countercultural practice?

In closing I return to Brodsky sounding like a Zen master offering a sort of koan on boredom. Quote,

For boredom is an invasion of time into your set of values. It puts your existence into its perspective, the net result of which is precision and humility. The former, it must be noted, breeds the latter. The more you learn about your own size, the more humble and the more compassionate you become to your likes, to that dust aswirl in a sunbeam or already immobile atop your table. Ah, how much life went into those fleck! Not from your point of view but from theirs. You are to them what time is to you; that’s why they look so small. And do you know what the dust says when it’s being wiped off the table?

“Remember me”, whispers the dust.

May we reclaim our countercultural roots and resist the conditioning of our age. May we find the courage to sit with our boredom and discover the infinite possibilities that arise from simply being present.

Peace.